My consulting firm asked several native New Yorkers why they bought an SUV for the streets of Manhattan. Oddly enough, the number one response was, “What if I choose to go off-road?”

Off-road. In the financial and cultural nexus of the U.S. On an island.

The more we probed, the weirder their responses got: “Oh, it’s because I go off-roading on the weekend.”

Even if some respondents were truthful and really do go off-roading, is it rational to buy an SUV in Manhattan? How do these people justify their irrational buying behavior?

Answers to subconscious motives are found at the subconscious level — not at the conscious level that marketers usually focus on. Researchers have a duty to probe into the subconscious to find the true source of our decisions, preferences, feelings, and beliefs.

For centuries, theologians, philosophers, and scientists studied the unconscious to understand why we do what we do. Half a century ago, Ernest Dichter founded the field of motivational research with consumer interviews to explore consumers’ non-rational motivations. Today, marketers recognize the emotional ebb and flow influencing individuals’ choices. Much of human behavior is motivated by the subconscious.

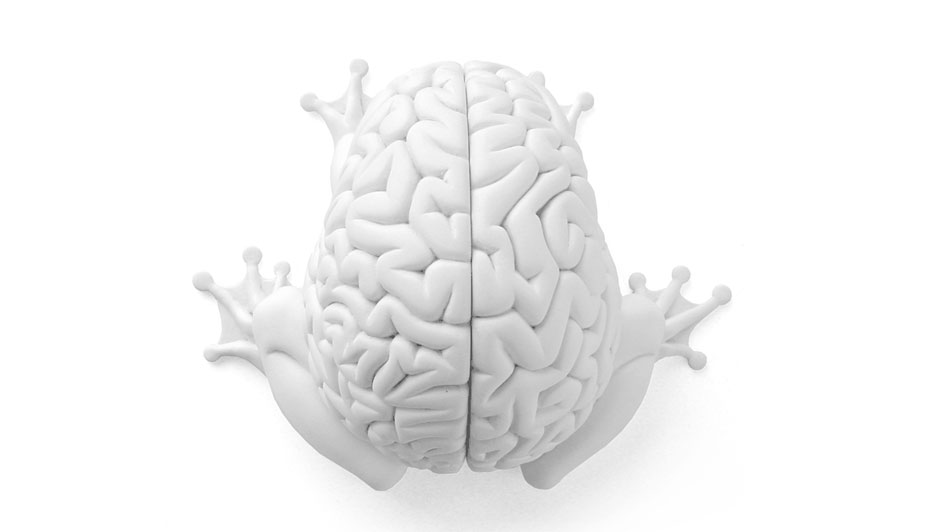

I call it “the lizard brain.”

It isn’t rational—it’s instinctual. It doesn’t shut down when we go to bed or on vacation. Every second, it dictates how we act, think, and feel. It pervades every dimension of our lives.

Given that fact, what’s the use in spending tons of money to carry out elaborate market research? Why ask the rational mind about irrational behavior?

SEE ALSO: The Brand Myth: Demystifying Brand Development

People inherently want to rationalize their behavior. We, as a species, elevate intelligence as a desirable quality. When others confront our irrational thoughts or actions, we will strive to appear intelligent nonetheless.

“Oh, your e-mail must have ended up in my spam folder — that’s why I didn’t respond!” “Your updates never show up on my Facebook feed.” “Honey, of course that’s not what I meant!”

Quite simply: Humans lie.

We all consciously fabricate these face-saving stories. In one out of ten interactions, married couples lie to each other. This figure skyrockets to eighty percent when it comes to spending habits. If married couples do this to each other, imagine what participants in market research will say.

In fact, in a recent train ride I eavesdropped on a forty-something, suit-wearing professional talking to her colleague. She boasted how she had hoodwinked that she was a premium subscriber of Skype to earn $300 for a focus group research.

A graduate student I know did the same thing. He participated in a consumer focus session targeting college students who ate macaroni and cheese straight from the box. Now, macaroni and cheese isn’t even sold in his native country — but he extolled the virtues of this delicacy as though he ate it for breakfast every morning. He could have told them the truth, but it would have been irrational to sign up for a study on a product he knew nothing about.

So he said something to make himself look intelligent. He showed me his CDs and T-shirts the $100 participation money bought him.

Like icebergs, at least ninety percent of our emotional and intellectual awareness resides far below the surface in the murky depths of the subconscious. So why do market researchers only focus on the ten percent of behavior visible? Why try to understand the whole iceberg from just the fraction we can easily see?

Forget charting the rational mind. To understand consumer behavior, you have to wander into the dimly lit depths of the lizard brain. Marketers need not look for intelligence — they need to look for instinct. Photo credit: “lapolab” / Foter / CC BY-NC