There are different ways to look at branding and it is certain that I have a very different one.

It is fascinating to imagine the journey of a brand that starts with an idea from an entrepreneur. Personality, interests, and environments bring to life ideas, leading to a project and the first version of a brand, followed by ongoing cycles of brand innovations. Brands tend to be perceived as intangible, but the whole process of branding is definitely chemical, physical, and biological: even the slightest brand association is supported in our brain by dozens of neuronal links and is constantly shaped and reshaped by our experiences!

With this physical dimension in mind, we can imagine how brands are also moved by forces that are yet to be fully understood and summarized into their own Principia. It is fascinating to consider how emotions or memories can activate brand messages; to explore the role of design and colors in forming brand perceptions; to imagine these thresholds that we jump over when forming a preference for a brand or considering a purchase; to admire the power of the alchemy that enables loyalty to sustain over time. Digitalization is changing our interaction modalities and adding a supplementary layer to the system. The forces that shape brands’ perceptions today are the result of highly complex underlying systems including everything from neuroscience, biology, psychology, and semiotics up to microeconomics and behavioral sciences: understanding how branding works is an infinite field for study and amazement.

Our ambition is to observe the phenomena of branding, practice branding, and unveil the principles of branding. Here are a few observations about the growth of branding in China gleaned over the past years.

RELATED: How Big Brands Foster Global – Yet Regional – Loyalty and Awareness

2005-2008

Pragmatic and mercantile stage with low innovation. Brand awareness and brand esteem are determinant.

It is a period dominated by a form of classicism in continuity with the previous decade: the context is a fast growing China economy, with companies looking inland and to lower tiers as a reservoir for growth. It is the epitome of fully optimistic, worry-free China, where the brands function as identifiers without the need of building in-depth associations. It is a thriving nation gearing towards the Olympics. It is all about being fast, present, loud, and obvious, tapping into the trend of mainstream adoption – even for the luxury brands characterized by the golden age of the monogram. The consumers are distracted by novelty; very few have built enough experience in dealing with brands in order to sacrifice exploration. There is no brand loyalty. What matters is the ability to monopolize the space, be it retail or advertising. It is still a quite traditional branding age with TVC and magazine ads holding a predominant role, not yet driven by the digital revolution that is about to come.

Foreign brands tend to be, at this time, only a name, often not translated into Chinese and seldom appearing in written form. Most of the CEOs, GMs, and brand and marketing managers even question the need for a local identity. The “foreignness” defines a very clear premium and niche space. Further adaptation in terms of relevance (beyond the notion of making a brand available and well-known) and differentiation appears to be premature and unnecessary. Big winners are the biggest brands that tend to already get recognition. Most consumers want not only to experience, but also to display what they are experiencing; they do this with a recognizable badge known by all, not just their peers. This is a time when Chinese consumers are very confident in the future. They are unwilling to project themselves into a company’s brand heritage. They are satisfied by floating on the surface of branding, and do not gain pride in being discerning and driven to individuality.

We only see a few FMCG brands innovating for China: functional biscuits by Danone and a slimming tea for women by Lipton.

Many Chinese brands are in the situation of being partly OEM for other markets, partly consumer brands. They feel no pressure in their consumer brand business that seems to be a nice asset, mostly handled through wholesale to the gigantic China market place. We see the emergence of strong FMCG brands like Wahaha, the strengthening of local automotive brands, the growth of sport brands like Li-Ning that have the ambition to conquer the world. These brands usually have very centralized decision-making capabilities and immature bureaucratic formations. They are fast, and they benefit from the local turf advantage, but they are neither process-oriented nor sustainable. Some of them have original approaches to innovation, working with their value chain partners to develop products and concept ideas (like Wahaha). It is one of the early signs of the China-specific consumer goods innovation model.

The first tier cities are evolving concurrently at a fast pace: Beijing is moving rapidly ahead, propelled by the Olympics; Shanghai is becoming a magnet for international media as they report on reviving the city’s past luster and making the most futuristic megalopolis of the 21st century; Guangzhou and Shenzhen are raised to international recognition by the strong manufacturing backbone of the Pearl delta regions. Shenzhen is a new city attracting talents from all over China. All these cities are the crucible for a new China lifestyle that blends influences from the West (American European) and the East (Taiwan, Japan and Korea). Hollywood is in China via the DVD stores, and Korean dramas are starting to fascinate China. It is the emergence of successful bakery chains and coffee chains. Bread and coffee are becoming part of the daily life of Shanghainese and to people in some parts of Beijing and Guangzhou/Shenzhen. It is the new signs of bourgeois life that replace or complement the pajama street-walking and long nails of days gone by.

We see urbanization, the rapid raise of real estate prices across the country, avid demand for new construction. Construction and manufacturing companies experience record growth. B2B and real estate companies are sophisticating their offerings in what has become the biggest market in the world. China starts to uncover needs for brand innovations in the least expected place. At that time and still for a few years, the most un-happening industry for brand innovation is the luxury industry in China.

RELATED: The C-Suite: David Chen, CEO of Strikingly

2008-2012

Brands become more innovative on product level. More ambitions for Chinese brands. Start of the strengthening of brands, but on new projects and opportunities, not at the core.

This second period is a turning point in the Chinese journey. China is no longer in the shadow, now benefiting from its status as a growing superpower. The Olympic Games in Beijing put China on the global stage and leave a lasting impression. The event has also created a platform for branding, as the attention of an entire nation is centralized and focused during the years surrounding the event. We see incredible branding campaigns from Nike and Adidas carving out their brand territories in the Chinese market as has seldom been done before (Maybe the 1984 Apple ad is the only comparable event in the history of branding).

With the crisis hitting the developed economies, China has become the hope of the world to sustain the growth of the global economy. Chinese travelers, the Chinese domestic market, Chinese manufacturing development, and China’s need for primary resources are a solace amid dropping demand in most other regions.

The global crisis is the spark that has ignited the evolution of branding in China. Now, the Chinese companies feel that their destiny is no longer just to copy successful models, but to take the lead, innovate, and push the boundaries. Internet brands are the first to capitalize on this new mindset. Now, OEM are barely a reliable way to imagine sustainable growth; instead, brands are pushing forward in the Chinese consumer market. At first, things seem to be continuing as they were, but before long FMCG brands start to meet a kind of invisible wall: they are no longer growing almost automatically, and stocks are piling up. This triggers a stronger need for developing brands that can sustain through relatively depressed times.

Chinese companies start to become savvier in terms of understanding the importance of the brand, resulting sometimes in epic fights over trademark rights, like the battle over the trademark WangLaoJi.

With decades of opening up in different markets and several years into the WTO, China is now becoming an increasingly competitive market in almost every industry. We also see increasing demand for innovative product concepts that will not only try to bring an existing concept to China, but also adapt and transform it to make it more relevant, more different. This is often happening at the product level more than at the brand level. We are looking for innovation of the persona to create localized variants, but not yet a revolution of the brand program for China. Some very emblematic projects for Labbrand represent this trend—we work on developing product positioning through flavors for industries including dairy, quick service restaurants, fruit juice, and others. We also see a luxury brand Shangxia created under Hermes Group with what appears to be Chinese DNA, reviving Chinese traditional crafts into finely designed fabrics, homeware and accessories. This is a very ambitious move, very admirable and ahead of its time, as the Chinese consumer has yet to revalorize their own craftsmanship tradition.

Quality entertainment and culture makes it also relevant for brands like Disney to foster a faster pace of development for their brands. Marvel is a successful example of this with its multitude of branded heroes.

The digital space has become more and more innovative and starts to play a much more important role than in most western economies, enabling the development of more advanced services and creating higher expectations.

To summarize, this turning point put differentiation and relevance of brands at the center again. It is no longer about fame and mainstream, it is about making a difference, about surprising and delighting the consumer. It is now a competitive era, but it is just the beginning of this intensification.

SEE ALSO: 3 Experts Answer 10 Key About Destination Branding

2012-2015

Strengthening of brand relevance and differentiation, first investments into brand knowledge

After the Olympics, Beijing continues to grow but somehow closer to traditional Chinese values, leaving Shanghai almost alone to represent the cosmopolitism that it once tried to contest. Shanghai, further propelled by the World Expo in 2010, continues to be the favorite destination for multinationals, and becomes the regional hub for many companies. Shanghai is more permissive to foreign influences and we see a tremendous change in the city in these years. Shanghai now has 256 Starbucks and counting – the 3rd most of any city in the world, and compared to just 137 in Beijing. And this is not just about coffee and bread. You can now see literally hundreds of Olive Oil brands in supermarkets. The selection is huge. Specialized large scale supermarkets like Olé are mushrooming in the city with an incredibly wide range of brands for any category of packaged food. Guangzhou and Shenzhen are close behind and Chengdu has started to modernize deeply as an influential center for the West. Shanghai is a fascinating place in which to project the future of China: a place of experimentation, a place where all global trends are crossing. It a place of harmonious coexistence of different trends, such as increasing body efficiency through vitamins and improving wellbeing through nature-inspired products. These intersections are mediated by a growing variety of consumers. Gaps are becoming bigger and bigger between younger consumers and mid aged ones. More profound segmentation is taking place.

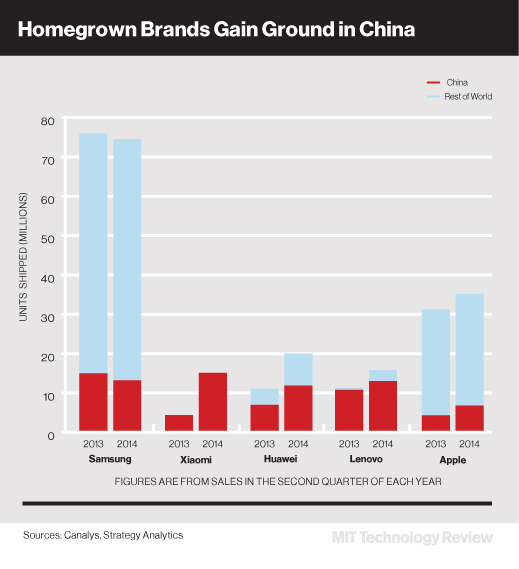

At the same time, we witness the first global successes of Chinese brands, with Chinese mobile brands rising to extreme success in India and even worldwide (Huawei, ZTE, etc.). This is motivating for all Chinese brands, even if a large majority of them just set out to be successful in their domestic market. Global public relations, digital platforms, and social media are now the type of activity that Chinese brands are engaging in consistently and on a global scale. Chinese brands look for brand building help. It is part of the China 5-year plan. There is no future in pure manufacturing; it is in the state’s best interest to develop strong brands that can maintain Chinese economic growth. Added value and a brand mindset are the only way to go.

As companies strengthen their brands by making them more relevant, a change is in the air: this time it is not a tactical move but a clear ambition to set a lasting direction. At Labbrand, we see increasing demand for brand positioning work for already established brands. The tactical moves previously used for some innovative products are now being embraced by the core product ranges and industrialized as central strategy. For the fashion industry, we see that entire collections are using China trends, fitting Chinese tastes.

At the same time, for foreign brands the situation has totally changed. There is now an increasing number of affluent Chinese that can buy imported products. Packaged food brands are increasingly ready to adapt their products and translate their packaging rather than sticking on labels. This change started just a few years back and we are currently in the middle of it.

For foreign luxury brands as well, there is a totally new situation. Chinese consumers know they are important and are not only expecting to be impressed by the “foreigness” but also to be embraced.

Digital space is dominated by local brands, but this last period also bears witness to the success of a few international players including LinkedIn who successfully develops in China under a name designed by Labbrand called 领英. Local digital brands like Tencent are credibly innovating for the world, and the fast-growing Wechat is set to become an indispensable tool for operating within the mobile sphere.

Image source: Michael Davis-Burchat, Bridge IP Law Commentary, Technology Review