Everyone hates advertising until they lose their dog.

No matter how much you hate those commercial interruptions, as soon as Fido finds freedom, owners want to figure out the best way of stopping people in their tracks to find the family’s favorite member. The dog owner’s brief? How do we disrupt people’s day to get them to look for Mr. Woof.

The same is happening to brands with a focus, or an increased interest, in digital. Talk to any digitally-orientated startup and you’ll hear the same phrases time and time again:

- We want our brand to be agile (we barely have any staff or process).

- We want scale (we are tiny, but want to be massive).

- And the problem child: we want to be disruptive (we want to invent something so good everyone will drop what they are doing and come to us).

Now all of these values are entirely understandable as a business plan. The founders probably grew frustrated with lengthy sign-off processes at big companies and started their own gig, so agility feels vital. They want the power, influence, and riches that come with scale. They admire the surface of the biggies that have made it. The Googles. The Apples. The Ubers. The Airbnbs. All of these traits are admirable and useful in the design of a company, but what about the way the brand is depicted and experienced?

Agility? Great. Everyone expects an instant response from digitally-focused brands.

Scale? Sure. Even smaller services like Citymapper or Shazam feel connected at scales that are useful without being exhaustive.

Disruptive? Erm…no. Do not disrupt my day. Complement it, aid it, help it – but with my permission. Even previous fans of “disruptive thinking” (i.e., advertisers ) have moved on from jumping out at you to inviting you into a conversation. Or, more succinctly known as an “engagement model.”

There’s the rub. Founders and enthusiastic members of digitally-focused businesses create a brief that is agile, scaleable, and yep, you’ve guessed it: disruptive. But they rarely embrace the quality that makes digital work so powerful: the chat, the charm, and the play.

This disruptive-powered brief is leading many design companies astray, creating work that’s barely viable and certainly unlikely to contribute to a lasting, useful, and valuable way of representing the product, organisation, or service to the (eventually) paying public.

Some disruptive design thinking makes desperately basic errors in branding. The recent rebrand of Addison Lee, the once darling London private taxi hire, has embraced a color that’s certainly disruptive. An acid-level fluorescent yellow that is so bright it renders words entirely unreadable in print. Disruptive? Yep. Strategic? Not quite. It will most likely need to be amended after the results of their expensive outdoor poster campaign are evaluated.

While the initial rush of gamma rays and sour brews raised more than one eyebrow and even more elbows, it’s now just as confusing as it crosses over to the mainstream. Many a city barman now hears, “Erm, so what is this?” as another customer is met with an unintelligibly-labeled can. In the rush to disrupt, brewers have simply confused customers; and, in the rush of mimetic isomorphism, everyone looks the same.

Meanwhile, it was The Meantime Brewery who took home the big money prize when they were acquired by SABMiller. How did they do it? They took a genuine and simple idea of being London’s craft brewer and stuck to it, gaining significant distribution and becoming London’s new beer of choice. On tap. On demand. On brand.

The truth is that brands, like people, follow themes. Move too far from a central theme and you not only disrupt a sector, you alienate and confuse its audience.

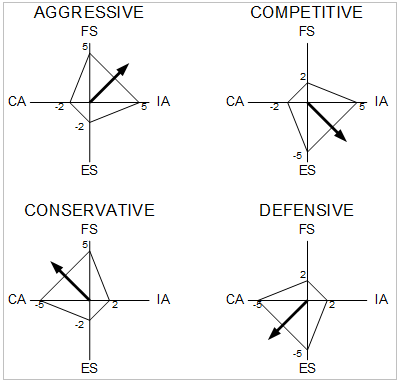

There’s a lot to be said about being in the middle of a strategists’ matrix. The centre of the diagram is often the most powerful place to be — and certainly the most balanced. It just doesn’t raise the headlines that outlier brands do. Radical thinking still has a terrific role to play in mass market branding because the masses crave entertainment, but what they resist is seismic shifts, and that’s what a disruptive brief asks for.

For example, Apple released a significant update to the iPhone operating system and one of the most notable inclusions was the shift from pure function to play in messaging. SMS is now the communication channel of choice, and the usually minimalist Apple has chosen to include highly sophisticated animations of confetti, balloons, even fireworks and lazer shows. Why? Because they’ve seen how Snapchatters have flocked to channels that offer more entertaining ways of getting people together. Play, not purity, won the day.

The simple — but often forgotten — rule is that brands exist to create monopolies within their audiences. They are competitive by nature; it’s the only reason they are there in the first place! The words circling digital startups and traditional brands with a newly invigorated digital focus (feeling competitive and ready for combat) are: scale, agility, and disruption. They are fighters’ words; they describe Muhammad Ali branding on a surface level.

But it’s not disruption that brand briefs need to embody for a win with the masses — and let’s be clear, brand briefs are not to be confused with app business plans. It’s the collective power of adaptive, nuanced, and entertaining branding that can cheer, enhance, and amplify an audience’s emotions.