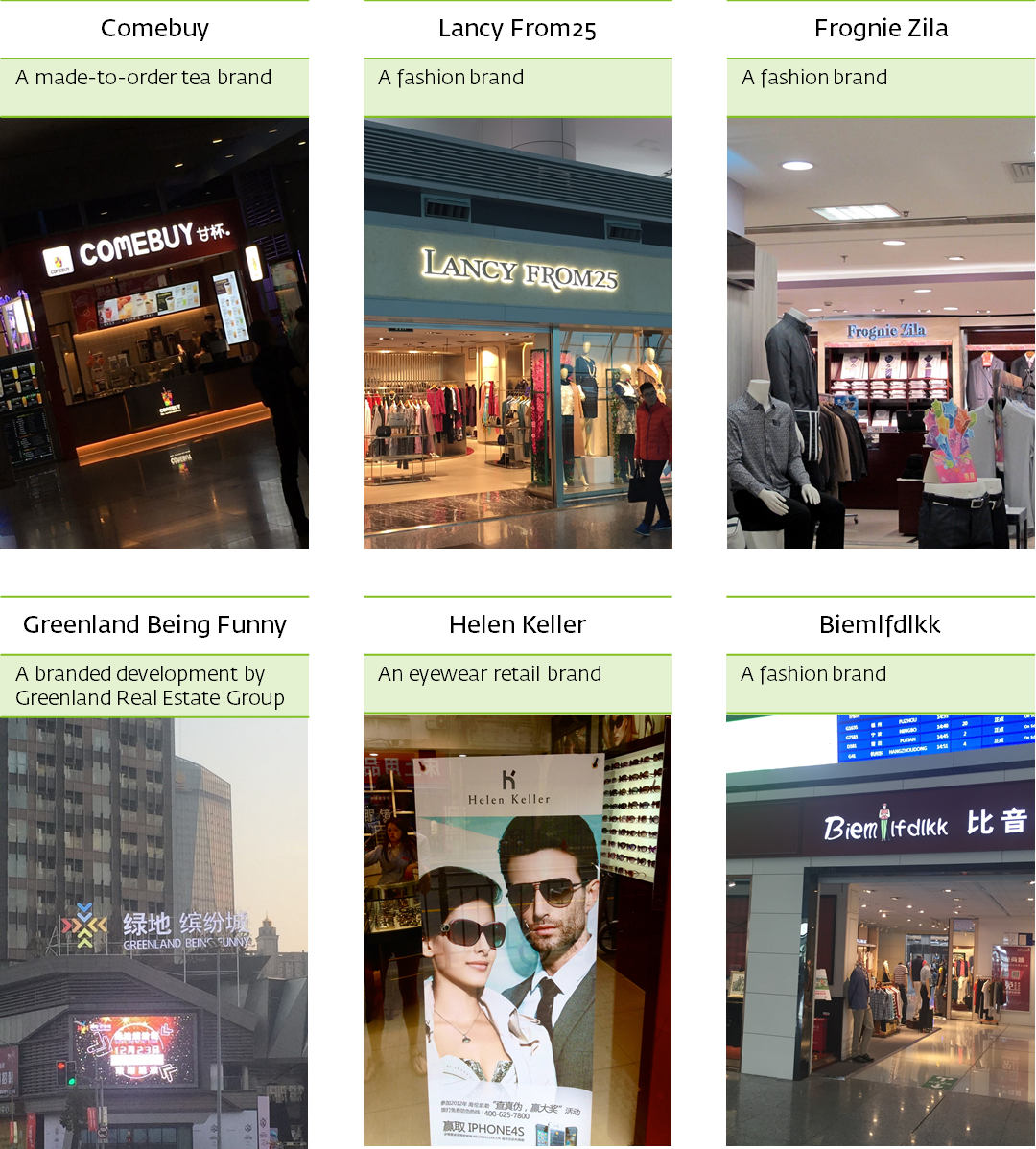

At first glance these 6 brand names look terribly wrong but upon a closer look they are almost all to some degree memorable and associative. I came to the realization that their imperfection may actually come from a difference of sensitivity to intertextuality between Western readers and Chinese readers, especially regarding alphabetic names in China. Behind these notable imperfections, once defined, we can actually uncover new naming forms and creativity at play that can serve brand namers for their future work.

- How do they standout?

- Are they easy to memorize?

- What associations do they immediately create?

- What connotations might they have in addition that could be triggered?

- How easily can they be used on general touchpoints?

- What do they tell me about the brand owner’s ambitions?

- How much would I trust this company?

This analysis is done almost imperceptibly and effortlessly and it is part of the pleasure of discovering an urban scenery. When a name is outstanding, it surfaces from the subconscious and usually prompts me to make a mental or physical note, sometimes to take a picture as evidence. I have collected a few names spotted on the streets, in airports, and in the media both in Shanghai where I live and during my trips to other Chinese cities that I feel can be labelled fairly and unanimously as “bad names.”

Surprisingly, if I were to follow the usual objective criteria to evaluate the names – such as memorability, associations, industry codes, attributes of the brands and so on – it would be difficult to find compelling reasons to consider them inappropriate.

For example, ComeBuy is very memorable; it sounds in Chinese like “GanBei” [干杯; gānbēi] which means either “bottoms-up” or “sweet glass”, two connotations that are compatible with a made-to-order drink.

But there was something more than the usual objective criteria that made these names so bad. Something linked with the capacity to appreciate the beauty of a name and the use of intertextuality as a filtering criterion for such an evaluation.

Let’s take them separately to understand better what makes these gems imperfect.

1. ComeBuy

ComeBuy’s issue is that it says, in plain English, “Come and Buy” which is consumerism on steroids that echoes a lack of consideration for client relations. It tells the customer what to do. Unless you have some good humor or can read between the lines into the context of the close Chinese pronunciation, it is hard to adhere to this name choice.

But on the other side, the English words are simple and most Chinese could read them. For most Chinese, these 2 words “Come” and “Buy” are simple words and the combination is playful and lighthearted. They would not have the same cultural sensitivity towards consumerism and would not develop a negative relation towards the concept. The name actually could refer to building strong affinity or loyalty with a group of consumers, especially when you consider the name’s phonetic closeness to the Chinese word for “cheers” – an action done together. Such open mindedness towards the concept is not natural anymore for a Westerner but is still widespread in China… the more I thought, the more I became balanced in my judgement of this name.

2. Lancy From25

The most obvious mistake is the grammatical error of a missing space in the latter half of the name. The brand name also fails in that the number cuts off by a demographic: younger consumers may think the brand a good purchase, but consumers over the age of 25 will believe it’s too young or immature.

The deepest problem, though, is what it says about its owner: an overly-practical boss that decided to shortcut his message to hit a target demographic without trying to use metaphors and sounds, who instead went into a marketing book-like descriptor. Somehow it seems to fail in the same way as the previous name, ComeBuy.

However unlike ComeBuy which delivers some element of syncopation and openness, the name Lancy From25 suggests that its clothes are meant for one age group and one age group only. The irony in the name is that by trying too specifically to define a target market in its name, it becomes inflexible and imposing for the wide range of consumers aged 26-40: you consumer, you are not allowed to enjoy and appreciate the art I am creating for you, instead you are reduced to the role of a demographically defined agent!

The lesson is that Chinese business owners tend to be more practical and less sensitive to the established codes of elegant behavior that underline business creation in many Western countries. These codes command a more metaphoric and evocative name choice, avoiding overly descriptive names and certainly marketing-type classification words (CSP+, over25, etc…).

This is even stronger in Fashion and Lifestyle industries. With mounting exposure to the international cultural text of entrepreneurship, local Chinese entrepreneurs will become progressively more receptive and embrace the need for a more subtle approach to naming. We should see less of these types of names in the future.

3. Frognie Zila

A disturbing combination of Frog and Godzilla, is this a brand for toys? The association carried by the semantics bring Western audiences into a space that is ungracious and far from the elegance of premium Italian menswear.

But bring something else into the picture, Ermenegildo Zegna. You may not have thought about it when first reading Frognie Zila, but let’s look at it: “Fr” and “Er” are almost identical visually (just one “stroke” different) and we find a “gn” in both names. There is a Capital “Z” and a terminal “a” in both names…quite a lot of similarities despite a very different reading.

Chinese people see the alphabetic name more than they read it; the borrowing of code therefore emphasizes more of the letter shapes and disregards the issue of semantic denotations and connotations. The semantics in the name, in particular, are alarming; I can only encourage Chinese entrepreneurs to develop a sensitivity for that as well and gratify us with names that please an even wider global audience!

From a purely verbal identity perspective, Chinese consumers have minimal recognition of the name (there is no Godzilla in Chinese culture; frog is not read as evidently as for a Western English speaker). This illuminates the importance of the underlying Chinese name as the verbal identity asset which carries brand equity in China, while the alphabetic name functions as a more visual asset and plays a lesser role in anchoring the memories and brand associations.

In an increasingly connected world, a brand name benefits from testing associations in different cultures and languages, and we have seen the rise of services dedicated to international linguistic checks in the last few decades.

4. Helen Keller

I chanced upon this name not while walking on the street but during an article discussion about this name, however, I still feel that this name figures into this list of gems. If you do not know about Helen Keller – as a French man I had not heard of her before discovering this brand in China – it sounds like a pretty contemporary and fashionable name. It reminds me of Calvin Klein and it could be a brand that is its counterpart in delivering a vision of urban, sleek, simple, but elegant fashion.

The issue is that the owner probably chose this name because of the story of Helen Keller. Helen Keller, as I discovered, is a famous blind woman that helped a lot of blind people by being a role model at the turn of the 19th century. It feels silly and offensive to use for an eyewear brand. I believe that even a big portion of Chinese consumers will reject this type of branding: the recently-revamped website shows an overly-simplistic display with no option for bi-lingual visitors. Compared to other thought-provoking campaigns from Diesel and Benetton, this one fell short as it is unlikely there is sustainable value that can create a durable relation with customers.

Formally a nice name, but the intertextuality here is inexorably damaging the brand.

5. Greenland Being Funny

This name sounds so inappropriate that I caught it while jogging in Shanghai. Even in the midst of the running effort, it was too hard to miss! The name is grammatically a phrase. As ComeBuy, it uses simple English words to do a transliteration. This can be almost acceptable in some cases, unless the phrase in English has a derogatory meaning, as is the case with this example. It is a long name that tries to convey the fact that it is a mall for a relaxed lifestyle, with an entertaining twist.

However, the name does not make it clear that Greenland Being Funny can stand out against the numerous malls that are quickly building up in China with digital components and modern style, such as touch screen navigational displays and multi-story elevators. The name, to some degree, points towards an outdated understanding of how to deliver impactful brand name associations in the highly competitive real estate development market.

BeingFun or BeFun, while far from perfect, would have been a better choice and an immediate improvement.

6. Biemlfdlkk

Is this seriously a brand name, you must think? Astonishing as it is that this could even be chosen as a brand name, it is. And it is quite a big chain no less – with stores in prime locations, such as the main railway station of Shanghai!

The name stands out but is not memorable. Empty shells are good for names as they can be populated with new associations and become a vehicle for the brand idea. This is actually a valid naming strategy: only having light connotation and association, sharing subtle codes that define a category or a trend.

Yet while it seems to be a unique name especially with the design of the logo, it fails to stand for something. Even if we break the one word into two parts “biemlf” and “dlkk.” Or “biem” and “lfdlkk.” Or even into three parts “biem” “lf” and “dlkk.” It seems so arbitrary that it really goes over the top. We cannot even make an association.

Conclusion

Alphabetic names may go very wrong in China. We have seen quite an impressive collection above, which is only the fruit of last year’s harvest. Chinese business decision makers overlook alphabetic naming and allow derogatory denotations, connotations, and intertextual associations that they will probably avoid when choosing Chinese names. By looking at what makes these brand names as faults, alphabetic brand namers can discover the mechanisms that we have taken as reflex and better understand what we pursue and how we pursue it when crafting a name.

China is an exceptional laboratory of creativity and is a place for brand pioneers and global namers to reflect on their art, evolving brand names from a necessary asset into surprising gems and magnificent diamonds.

A well-designed name encompasses these elements in order to be appreciated by the passerby. The quality – the full shine of the name – is only revealed to the eye of the reader who has been molded by exposure to various cultural texts, as designing such a diamond is not easy. Beauty has to invoke the right level of intertextuality, which is heavily influenced by the language of culture. This requires a fluency in multiple languages to perceive and project associations as a guide of local tastes.

To put this back in a broader context, Häagen-Dazs could have looked like an uncommon name a few decades ago when it was launched. Yet it has since stretched our perception and acceptance of what a nice brand name is, as it arrived on time to offer an expression for a premium space that was needed in the category. With the rise of Chinese consumers and their influence in the global economy, there is a lot to learn from the mechanisms that still allow the occurrence of “bad” alphabetic names in China, and what new verbal identity spaces could be created for the future brands of the world.

Images: Max Pixel, hans-johnson