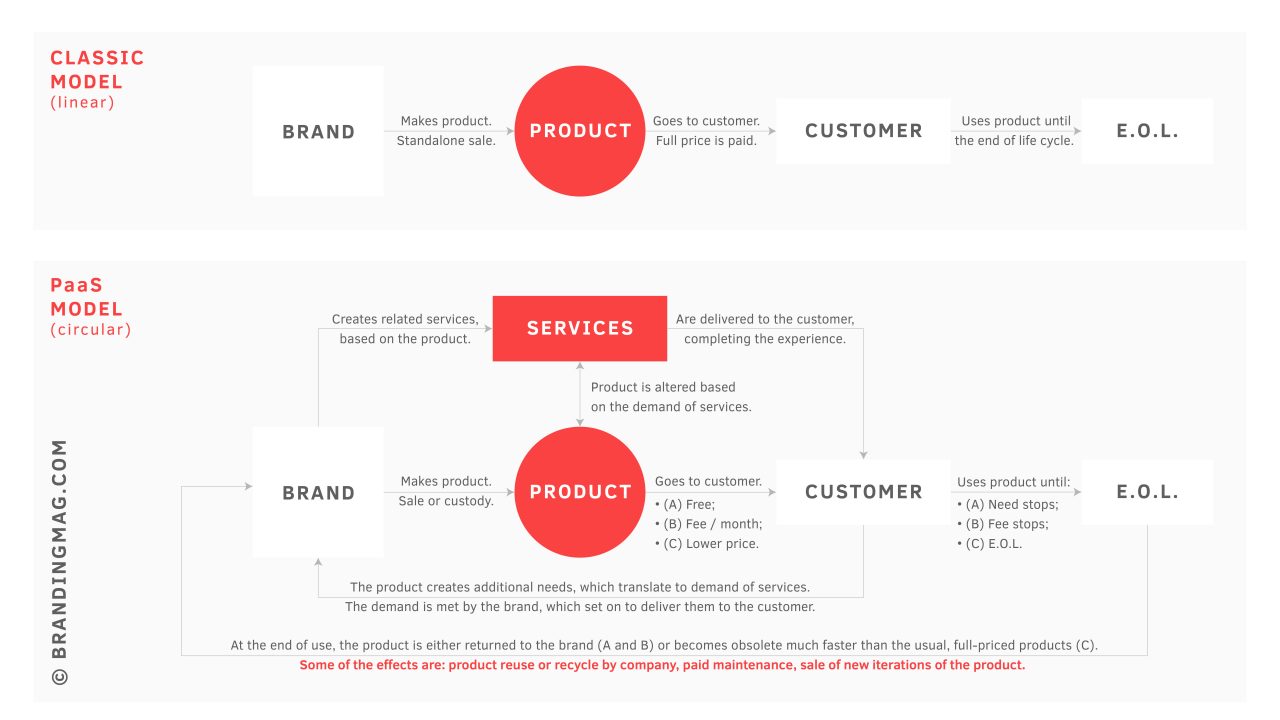

A high-rising trend among modern business folks is the “product-as-a-service” model, also known as PaaS. Originally coined by Rolls-Royce in 1962 as “power by the hour,” the concept has become increasingly popular in modern markets, as it seems pretty simple on the surface. In reality, however, the PaaS model brings about direct and indirect changes, making it difficult to implement in the right way. Revenue is likely to drop in the early stages and managing the transformation throughout the company can be quite a handful. From financial workflows to marketing strategies, every single aspect of the organization has to adapt to fit new requirements.

PaaS turns the product from a direct source of revenue to a supporting element for additional services. The product, sometimes offered for free, helps drive interest and request for services, which then become the main revenue sources for the company.

*Note: In the web market (e.g., Google Apps), PaaS is also used as an abbreviation for platform-as-a-service, which is an applied version of the model.

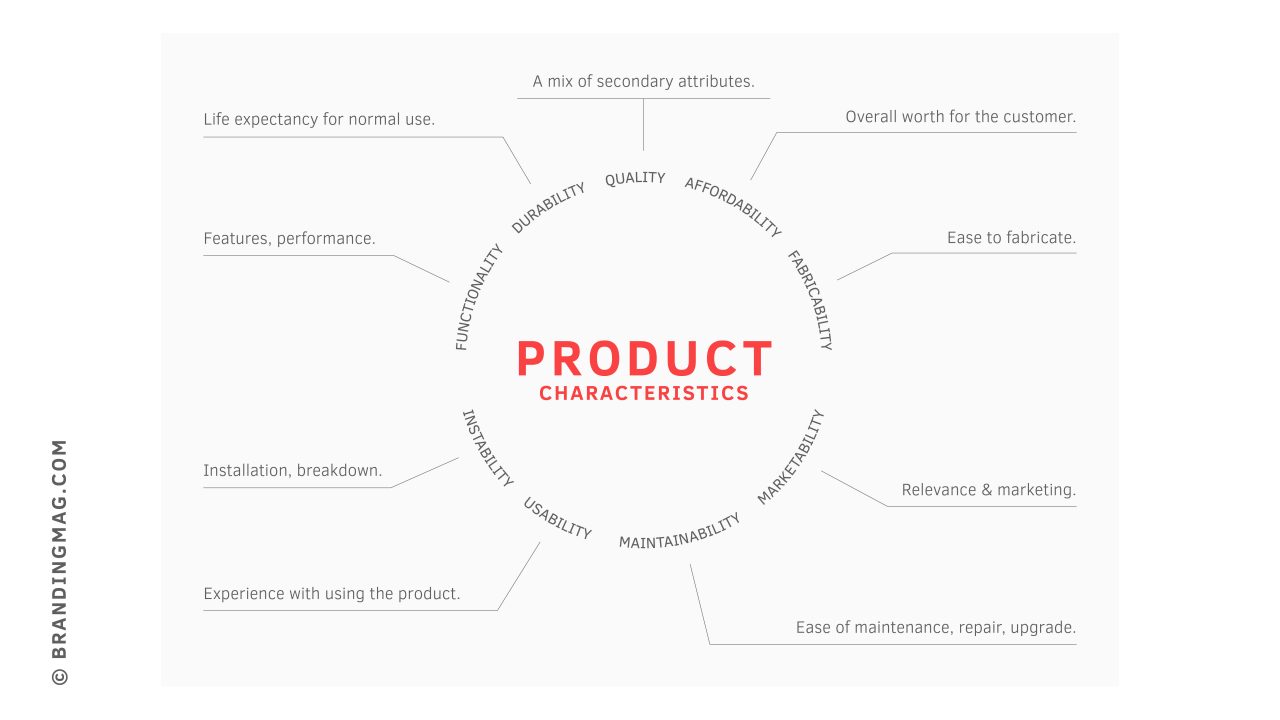

For product-selling brands, the actual product stands at the core. Everything revolves around it and its ability to satisfy the consumer’s needs. The business, brand, and marketing strategies depend on how well the product fits the market and its consumers, adjusting each of the product’s characteristics for that exact purpose. Until recently, the concept was simple: in order to stay relevant and competitive, the product had to meet the highest score for each characteristic and stay ahead of the competition. For consumers, this translated into a constant supply of innovation.

The adoption of the product-as-a-service model brought about some changes in the way companies evaluate products’ characteristics. Whereas in the classic model better characteristics translated into competitive advantage, sales, and brand equity, companies applying the PaaS model no longer strive to achieve those high scores. Each characteristic is evaluated based on its ability to produce auxiliary services which, in return, produce service-based revenue. This can turn out to be costly for not only the customers, but also for the brands.

How PaaS alters product characteristics

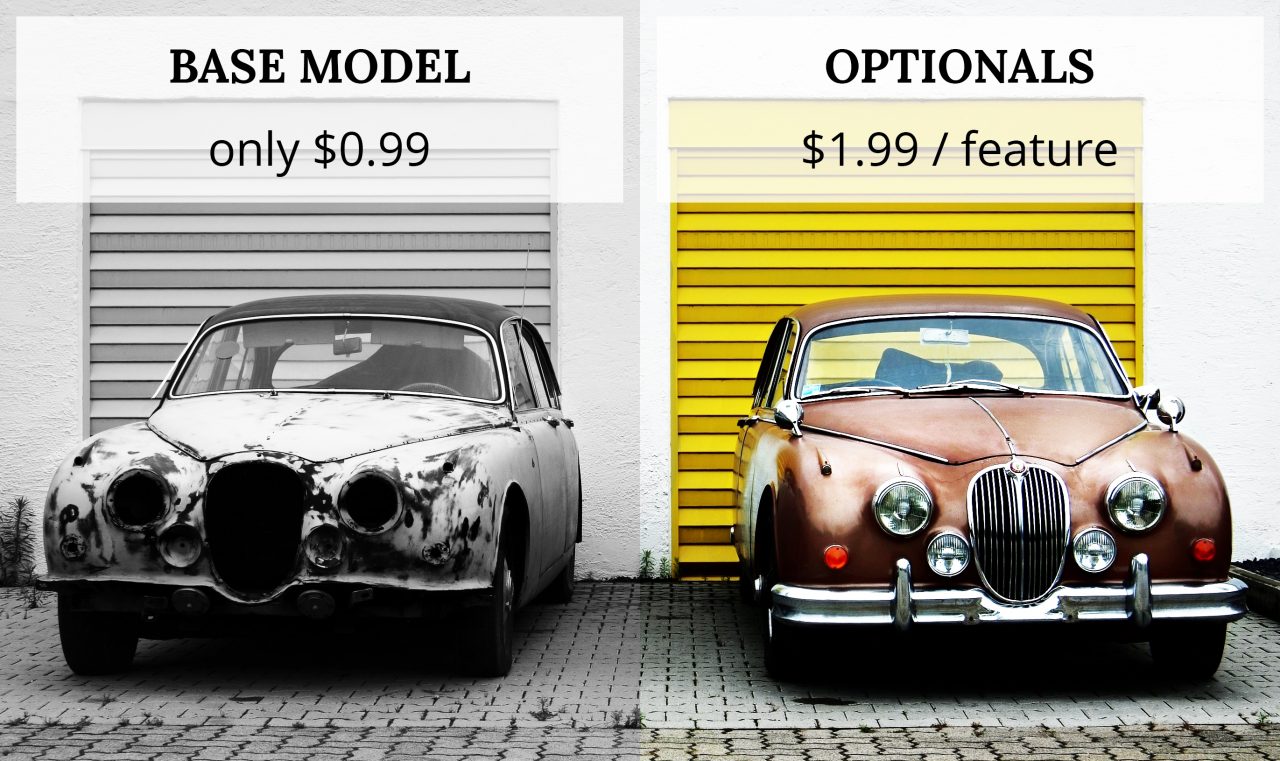

Functionality – Usually, this is the key differentiator. Better functionality makes for a better, more likable product for the consumer. Not the case anymore. In the PaaS model, non-basic features are removed from the final version and sold separately, as add-ons. This is a trick that looks good on paper, but also one that cost software industry giant Electronic Arts $6B in stock market value just last year.

Durability – A quality indicator that shows how the product will perform over time. Products that behave well over the course of their existence generate a high amount of equity for the brand, attracting loyal customers in the process. Yet, high durability is not something that PaaS-driven businesses desire. Auxiliary, out-of-warranty services and the sale of spare parts are beneficial for the company. The target is to design a product that will behave well during the warranty period and then gradually or suddenly deteriorate, forcing the customer to request paid, post-warranty services or acquire new product generations altogether. A move like this – a move through which the company purposefully and secretly slowed down older iPhones through software updates – translated into over 24 grand lawsuits for Apple in 2017.

Quality – Somewhat vague, this characteristic embodies multiple aspects of the product: aesthetics, context, variation, etc. An example of how the PaaS model affects product quality can be seen in variation. Brands are no longer offering a high variety of product options from the get-go. Customization is mostly served through additional costs or through 3rd-party suppliers of personalization options.

Affordability – Probably the only aspect that is improved by PaaS. The model relies on reducing the price of the base product, giving it away for free (in custody), or requesting a recurrent fee for its use. For the customer, this means cheaper products, but only from a very superficial point of view. Taking on a lease or subscription for a product, for a long period of time, can reveal an even higher cost, in the end.

Fabricability – This is the characteristic that helps PaaS brands the most. The model sets away customization and embraces standardisation, making it way easier for the company to automate and improve production flow. This effect can generate lower, end-market costs or higher revenue, depending on the pricing strategy of the brand.

Instability – Just like fabricability, instability is highly reduced by the PaaS model. Better control over product creation, distribution, and usage translates into more insightful data, which can help engineers and planners reduce product instability.

Usability – A characteristic that reflects aspects of functionality, durability, and quality. Usability tends to be reduced when the PaaS model is implemented. For greedy brands, this is an opportunity to increase usability through auxiliary services, add-ons, and paid customization. Not really a reason for customer joy, but certainly a money-making tactic for brands. Clearly, this can lead to a severe bleed in trust and equity. A poor take on the PaaS model led to the downfall of consumer printers and the rise of professional printers for rent. Consumer printers may have been cheap, but they had low usability scores “thanks” to poor printing efficiency and costly consumables.

Maintainability – Where customers suffer and brands win, big time. In the past, brands designed products to be durable and easily maintained by both customers and professionals. More skilled individuals (or those who couldn’t afford authorized interventions) could fairly easily maintain their own products. Changing a few car parts, switching a few computer components, or changing your mobile phone’s battery did not require a lot of expertise – not to mention that the products’ engineering allowed for such interventions. Nowadays, most products need to be sent to authorised specialists even for the smallest of needs. Vehicles have nuts and bolts that can’t be fitted back in or require strange tools to remove in the first place, while most mobile phones have non-removable batteries. It’s not that these aspects couldn’t be done in a different, more customer-friendly way; it’s just that auxiliary services produce additional revenue.

Marketability – A very good score for PaaS brands. Because characteristics that would otherwise be part of the basic product can now be sold separately, marketing departments have more toys to play with. Apple’s removal of the 3.5mm headphone jack helped them introduce a new, “revolutionary” product: the Airpod. And that’s not all… Apple’s marketing department certainly had fun promoting strings that attach to the Airpods, so consumers don’t lose them. The bottom line is that Apple used a PaaS strategy to actually sell overpriced headphones, and it worked.

When talking about marketability, we also address how long the product will remain market-relevant. Most of them become obsolete after a short period of time (due to their initial, deliberate design), while future iterations are not really different. Brands are essentially selling the same product for an extended period of time, marketing each iteration as a “new generation.”

As you can see, the product-as-a-service business model has a lot of beneficial implications for adopting organizations, but not as many for the customer and brand. In classic terms, brands strove to achieve the best product-serves-customer level and draw their spoils from the brand’s intangible value. Innovation and constant improvement were the high game of market leaders, leaving customers to enjoy a never-ending sea of products and features. This way of doing business has transformed brands such as Sony, BMW, or Nike into superlative adjectives. They have reached a point where their names or logos were a “good enough for me” endorsement for any product. Equity was high, loyalty and trust were high, revenue was high. The war of brands was all about who could better deliver on their promise, but it seems that fairness has never been an established characteristic of war, not even in that of products. Some companies seem to have adopted branding only because it was a trending tool and not because they really wanted to center their brands more on customers than revenue. PaaS is now the trending tool and brands are risking everything by going about this transformation the wrong way. It’s not that the PaaS model is an evil-doer, but it does bring with it a lot of temptations that seem irresistible to some.

How to actually keep your brand’s focus

From a strategic point of view, I can only suggest one thing to those desiring to follow the PaaS model: keep the customer and the product at the center of your activity. Great brands take a lot of time to grow and their food is trust – customer trust. When building or evaluating your brand, keep in mind that marketing follows brand and brand follows business.

PaaS can be beneficial, if used in the right way, but it can also lead to the brand being labeled as deceitful or untrustworthy by the consumers. And that’s a label that costs a lot of money to remove. Many PaaS paths seem tempting at first, but following them can have a serious negative impact on the long-term equity of your brand. So, before you start transforming your business into a PaaS-driven one, make sure that you weigh in the following aspects very carefully:

- A brand’s purpose is to resolve customer needs. Think of your customers with empathy and put yourself in their shoes. Would you still like a stripped-down version of the current product? Will it still serve customer needs as it should? If not, then don’t do it. Keep the product at the center of your brand. Innovate, make it better, and think of customer expectations in advance. Don’t just be reactive. Be proactive.

- If you really think that PaaS is the way to go, that it will get your company on the right track, then at least do it right. Yes, use the product to drive consumers towards other services, but make them supplementary. Design your services so that they come in addition to the product, empowering the present customer experience rather than restraining it.

- Take the honest approach and build a fair, post-acquisition strategy. There’s no way that a consumer will be happy to know that the warranty doesn’t actually cover anything (thanks to legal loopholes) or that fixing or upgrading their product will cost them as much as the product itself. For many users, these strikes are good reasons not to trust the brand anymore.

And, as a final thought, here is a summarized version of how product characteristics are being affected by the two variations of PaaS implementation:

Image sources: Dietmar Becker, Wccftech