The production, collation, and consideration of 1,200 post-it notes of information may sound like ‘data overload’, but the depth of detail that can be uncovered from this exercise — plus the visual impact of the resulting findings — will deliver unparalleled insight. Such insight is of particular importance when attempting to fix a broken culture.

This may not sound like an obvious brand-driven project, certainly to people who work outside of the creative industries. But if we remember a point that strategic brand professionals constantly stress — that brand is not about the logo — it’s soon easy to see the role that brand and design thinking could play in an exercise of this nature.

An educational challenge

To give context, it is helpful to consider a recent project to understand the current ‘state of play’ within an organization that is potentially on the verge of crisis. A design-focused approach was adopted from the outset to uncover the true situation — not just perceptions — and suggest opportunities to improve the internal culture before the future could be tackled.

This business operates in the education sector, although the methodology undoubtedly applies to virtually all private or public firms. In this particular example, the organization faced a seemingly relentless challenge to attract more and more students, with less and less funding, while maintaining exemplary quality standards, and all in the face of mounting expectations, a pressurized teaching climate and ever-advancing competition.

The senior leadership team identified that following a period of significant change — and with further change inevitably on the horizon — this was a great opportunity to go back to basics. It was a chance to answer questions such as ‘who we are’, ‘what are our principles’, ‘what do we stand for’, and ‘why are we different’.

If organizations can’t understand and remember all of that, how can they go on a journey together? And, equally, how can they bring others — such as students and their parents — on the journey with them?

Exploratory workshops

This sets the scene as to why all the organization’s 230 colleagues, from the senior leadership team through to part-time administrative staff, were invited to attend a series of workshops, as were a number of students, governors, and other educational partners.

The group sessions sought to explore what is great about working for the organization, what it is renowned for, how it compares in the marketplace, and what could be improved, to name just a few themes.

To ‘warm up’ the participants’ openness to all-things-brand, they were initially invited to align their organization to a well-known supermarket, writing just one word on a post-it-note to explain their selection. While the exercise was initially met with resistance — not least because supermarkets and colleges are markedly different — the resulting discussion was very telling. For example, it soon became clear that singular words such as ‘quality’ could have extremely varied meanings from one person to the next, evidencing that brand is open to interpretation and what defines it is often a myriad of things.

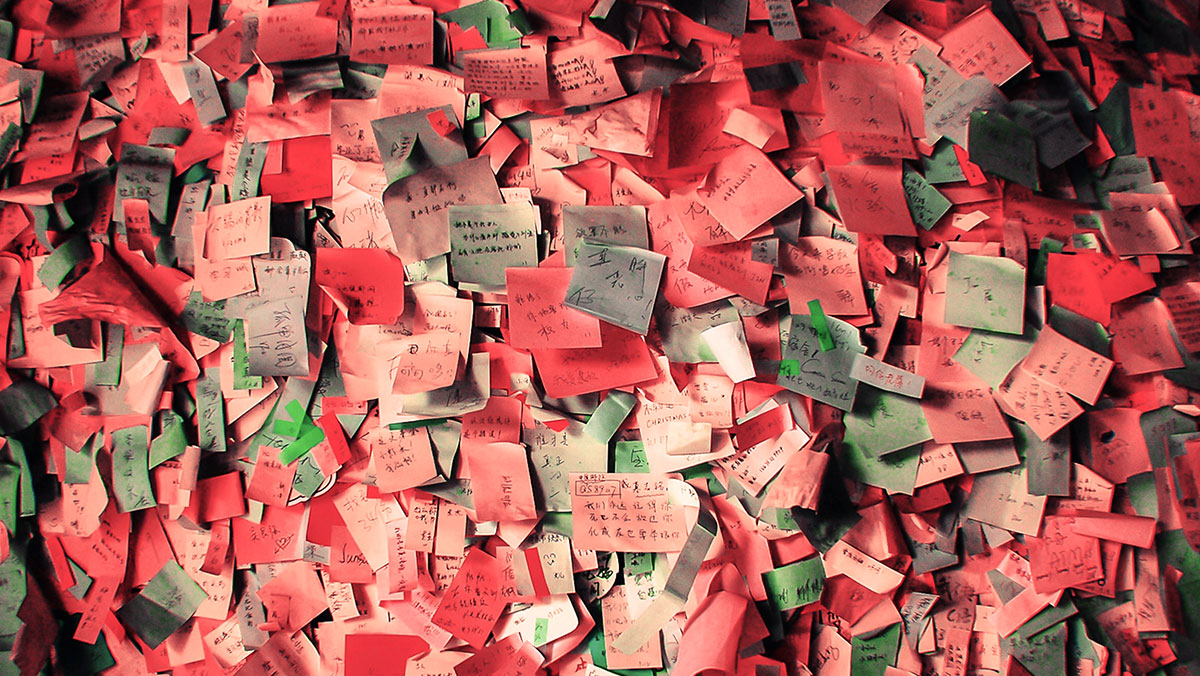

The core post-it-note exercise followed. Questions were purposefully simple, typically asking for one-line or even one-word answers to ensure participants did not overthink their responses. People were told to note their points, relatively privately, on colored post-it notes, before being invited to stick them on large sheets of paper that covered every wall in the room. This exercise followed the principles of the ‘rose-thorn-bud’ methodology, with the pink post-its (roses) representing what was good about the organization, green (buds) demonstrating the opportunities, and the blue (thorns) showcasing the lesser positive points, which could perhaps form part of the root cause of the broken culture.

Distilling the findings

The 1,200 post-it notes were then clustered to allow salient points to be presented back to the senior leadership team, in a separate session, away from the college. This clear methodology gave context to a mass of data and helped contextualize what may otherwise have been considered an overwhelming volume of information.

Importantly, ‘theming’ the 1,200 pieces of brightly-colored paper in this manner, meant they could easily be mapped against the organization’s currently articulated mission statement and values. This provided a really powerful, digestible, and effective way to distill the breadth of information down to a handful of must-know points. It also allowed the post-it-notes to do the talking — it couldn’t be dismissed as feedback from an external party that doesn’t truly understand the organization. And it clearly demonstrated that while the college may say certain things, these points perhaps don’t ‘show up’ in the eyes of the people who matter — the employees.

Every identified mismatch, however minor, was seen as an opportunity for change, a chance to review a potentially outdated value or practice that could otherwise contribute to a feeling of unauthenticity if it remained unaddressed.

What’s next?

The organization’s proposition — most notably its purpose, principles, and personality — is currently being rearticulated so that it can be replayed to everyone in the college as they move towards their future. It is hoped that, by rediscovering and redefining who they are, there will be a far greater chance of unity behind a shared vision, which should take people on the journey and encourage their collective appetite for change.

Again, visualizations will be crucial to conveying the new narrative back to the wider organization, with posters around college offering just one way to tell the story. This story won’t make external pressures go away. It can’t deliver a rapid fix. But it will hopefully help the organization rediscover its mojo, rebuild morale, and drive productivity and efficiency as they navigate the road ahead, together.

Involving some or all?

Meeting with a body of people — on this scale — is admittedly not an exercise for the fainthearted. But it needn’t be laborious, time-consuming, or restrictive in terms of timescales either. It can — and should — be fast and furious.

In the example above, groups of 20-30 individuals gathered in back-to-back discovery sessions which ran over 2-3 days and resulted in the unveiling of a significant amount of insight.

Would the same trends have been extracted if only a sample of people had been considered? Perhaps, if that sample was truly representative. But perhaps not.

Also, would the eventual ‘buy-in’ to any resulting project be as strong if only certain people felt consulted and therefore invested in the change project? Again, perhaps not, particularly in the cases of fixing a broken culture.

Sometimes, timescales or resources may dictate that sampling is genuinely the only option when undertaking such stakeholder research. But if this option is chosen because it is merely deemed a quicker fix, it must be accepted that the successful evolution of the brand project may be jeopardized.

To proceed or not to proceed?

Investing in the support of an external brand specialist may be the last thing on an organization’s mind when trying to rebuild a broken culture, especially if the situation is reflective of a business in crisis and potentially limited financial resources. To an extent, this is perhaps understandable.

However, the cost of not resolving the situation is undoubtedly far higher.

So, whether professional help is sought to mend a broken culture or not, the investment of time needed to undertake this visualization exercise and involve every impacted colleague, is certainly not something that should be avoided.

Cover image source: Victor He