Quietly but surely, cause-related marketing emerged as a major trend in Japan in the 2000s. Instead of simply sending positive messages to society, companies and advertising enterprises began aspiring to facilitate activities that could actually benefit society through the framework of marketing campaigns.

One framework involved donating a portion of product sales to a good cause. Most of those campaigns were designed to turn users of expensive or luxury brand goods into loyal customers and to differentiate those brands from low-priced products that had been commoditized. Sales even increased for many products marketed in this way.

In Japanese, the word advertising is written using Kanji characters that mean “widely inform.” However, members of Japan’s advertising industry had started questioning whether their mission was only to inform consumers. They saw cause-related marketing as offering the possibility of both boosting product sales for clients and benefiting society.

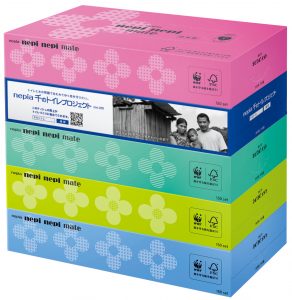

I felt a sense of excitement when I became involved in the Nepia (a popular Japanese household paper brand) 1,000 Toilets Project, launched in 2008. It provided funds for installing toilets in East Timor by donating a portion of the sales of Nepia brand products. I visited the country to inspect many of the toilets that had been completed and still remember how impressed I was.

A few years later, the shift to cause-related marketing in Japan rose to another level following the Great Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami that struck the country’s northeast Tohoku region on March 11, 2011.

The disaster had a huge impact on how Japanese companies viewed their place and role in society. Even today, I believe some companies have yet to properly deal with the changes brought on by the 2011 calamity.

I remember transportation routes being completely cut off and affected areas isolated, like landlocked islands.

Three weeks later, I went to one of the areas as a volunteer and saw firsthand how money no longer served as a means of exchange in the region’s economy. Volunteers, whether acting as individuals or on behalf of companies or non-profit organizations, all pooled their resources.

Locally, supermarkets allowed spaces to be used for emergency shelters, while bicycle manufacturers provided people with bicycles on which to move around. Musicians played songs in the shelters and volunteers distributed food. In one of the shelters, I made a simple picture-book gallery using picture books sent in from all around the country and furnishings donated by a furniture maker.

Until that time, Japan’s corporate and non-profit sectors had been rigidly separate, but now people from both sectors were working hand in hand. Through that process, many companies came to realize that they had resources that could help solve challenges confronting communities.

One of those businesses was Yamato Transport Co. Ltd., a door-to-door delivery service provider that operates a distribution network covering every corner of Japan. In the aftermath of the disaster, elderly people staying in temporary housing units had become isolated, and some even died alone in those dwellings. To address that problem, Yamato Transport started offering a new service: checking up on elderly residents along their delivery routes. Its resources were recognized as helping communities tend to their elderly members.

Like Yamato Transport, a growing number of companies adopted an approach of contributing to society through their business activities and services, rather than just by making monetary donations. That was one lesson we learned from the 2011 disaster. The approach also followed a broad international trend: Corporations in other countries were making social contributions through core business activities. This idea of “Creating Shared Value” (CSV) was originally conceived by Michael Porter.

In 2020, we face another major challenge: Covid-19. It is completely different from what confronted the country following the 2011 disaster. Then, we had been able to distinguish between victims and those offering their support. This coronavirus outbreak, however, affects everyone and so is a serious problem for society as a whole.

Restaurants are struggling, due to fewer customers. As a result, the agricultural and fishing industries that supply them are seeing sales decline. Meanwhile, hospitals and clinics are being overwhelmed with patients. Individually, we are having to take various steps to help prevent the spread of the virus.

Measures for dealing with such problems must be taken across the board. To do so, it is essential to reconnect people who have been separated – due to stay-at-home requests and other restrictions – and help rebuild their communities. Since many communities needed help with rebuilding even before the coronavirus outbreak, the disease has served as a catalyst.

The internet is being used to connect consumers to farming and fishing communities, while hospitals and clinics have begun meeting with people and patients online. Little by little, initiatives like these are beginning to have an effect.

Bringing together people and rebuilding communities in response to the Covid-19 outbreak is also a new challenge for the advertising industry. Indeed, I believe it marks the latest approach to social contributions taken by Japanese companies.

Historically, there have been four approaches:

- First, advertising companies began creating socially conscious messages.

- Second, marketing campaigns were used to help improve society by, for example, donating income from product sales.

- Third, companies began designing businesses to benefit society.

- Fourth, companies have started creating communities that reconnect people who have been separated from society.

Since the early 1970s, clients aspired to have their companies contribute to society and, I believe, that has helped drive the growth of advertising companies in Japan.

To satisfy the requests of their clients, Japanese ad companies have offered overarching support and assistance which, in turn, has broadened their capabilities and operating scope.

Besides advertising, the ad enterprises can create far-reaching marketing campaigns, design businesses, and plan digital transformations to expand connectivity. In fact, their scope is now so wide that they can hardly any longer be called advertising companies.

The latest challenge for the advertising industry is just emerging. In the next installment, I would like to shift my focus and discuss some of the most recent findings of data-driven marketing and their relevance to society.

The first installment in the series: A Better Future, Part 1 – Socially Conscious Advertising

The third installment in the series: A Better Future, Part 3 – Will Data Create Dystopian Nightmares?

Cover image source: Tim Mossholder