My next-door neighbor has just gone out and bought himself a brand new, lime green Porsche coupé. It’s really standing out in my quiet street in southwest London, which is generally full of black Mini Coopers and white Range Rover Evoques.

A strange choice for someone who previously had a BMW i3 (fully electric vehicle) and a large Volvo SUV (combustion engine), the safest car on the market. It initially signaled a mid-life crisis, but I hadn’t realized that the Taycan is Porsche’s electric offer. Indeed, to the untrained eye, it looks very similar to a Panamera; there is no reference to electric, with no ‘e’ or ‘i’ in the naming, or equivalent branding on the back of the car. It got me thinking about how brands are approaching the brand portfolio strategy, brand architecture, and naming question when introducing electric models to the portfolio.

It’s an interesting area. Tesla hit the mainstream market hard in the developed world just over five years ago with an electric-only offering. A new electric car brand created from scratch, with no previous dirty polluting ancestors.

Finally, the electric car market had something sexy and aspirational to aim towards. Tesla exuded desire. Electric cars had become genuinely cool.

Now (as I write in February 2021) Tesla’s stock market valuation has gone through the roof, beyond the belief of many investors. “When will the bubble burst”, they are asking. Experts believe that Tesla is around 2-3 years ahead of all other electric vehicle competitors in terms of production capabilities. But those competitors are starting to catch-up. And there are some innovative players coming in and representing a serious challenge, in battery technology and in vehicle production itself, particularly in China, as well as other parts of Eastern Asia and in the US.

A crowded future ahead

If we cast our eyes forwards to 2025, 2030 even, the picture gets more competitive for Tesla. GM pledges to have 30 electric vehicle models on market by 2025, and VW Group pledges to have a whopping 70 models by 2030. Other players are also putting out ambitious targets in this space.

While Tesla dominates the market capitalization, sales of its Model S and Model X are falling, and Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi and Hyundai-Kia all sold more EVs in Europe than Tesla did in the first nine months of last year.

According to a recent article by The Economist using Bloomberg’s data, electric vehicles currently make up 3% of all car sales. That figure is predicted to rise to a third of all cars by 2030, and almost 60% by 2040. By that time, 5% could also be made up of hydrogen fuel-cell drivetrains, leaving internal combustion at under 20%.

Some start-ups in China and the US are seen as Tesla copycats and serious challengers – Nio, WM Moto, Xpeng, Li Auto (from China), Fisker, and Lucid Motors (in the US), amongst others. Others are mainstream players in mass markets offering a greener solution, some are premium and luxury players offering the sporty element of Tesla backed up by a legacy brand. Others target specific needs and desires, such as Lordstown, the world’s first electric pick-up truck, and Canoo, offering electric vans. Even the big tech giants are getting in on the action when it comes to electric, autonomous vehicles. For example, Apple is pursuing to build its own self-driving EV, with talks of Hyundai-Kia to step in for production.

LE: Hyundai-Kia announced that their deal with Apple isn’t going through.

With such a change about to occur, electric vehicles will become the norm. Given the life span of such high-performance machines, it’s worth looking at the brand portfolio strategy and brand architecture question now, with a long-term view.

The E-brand strategy

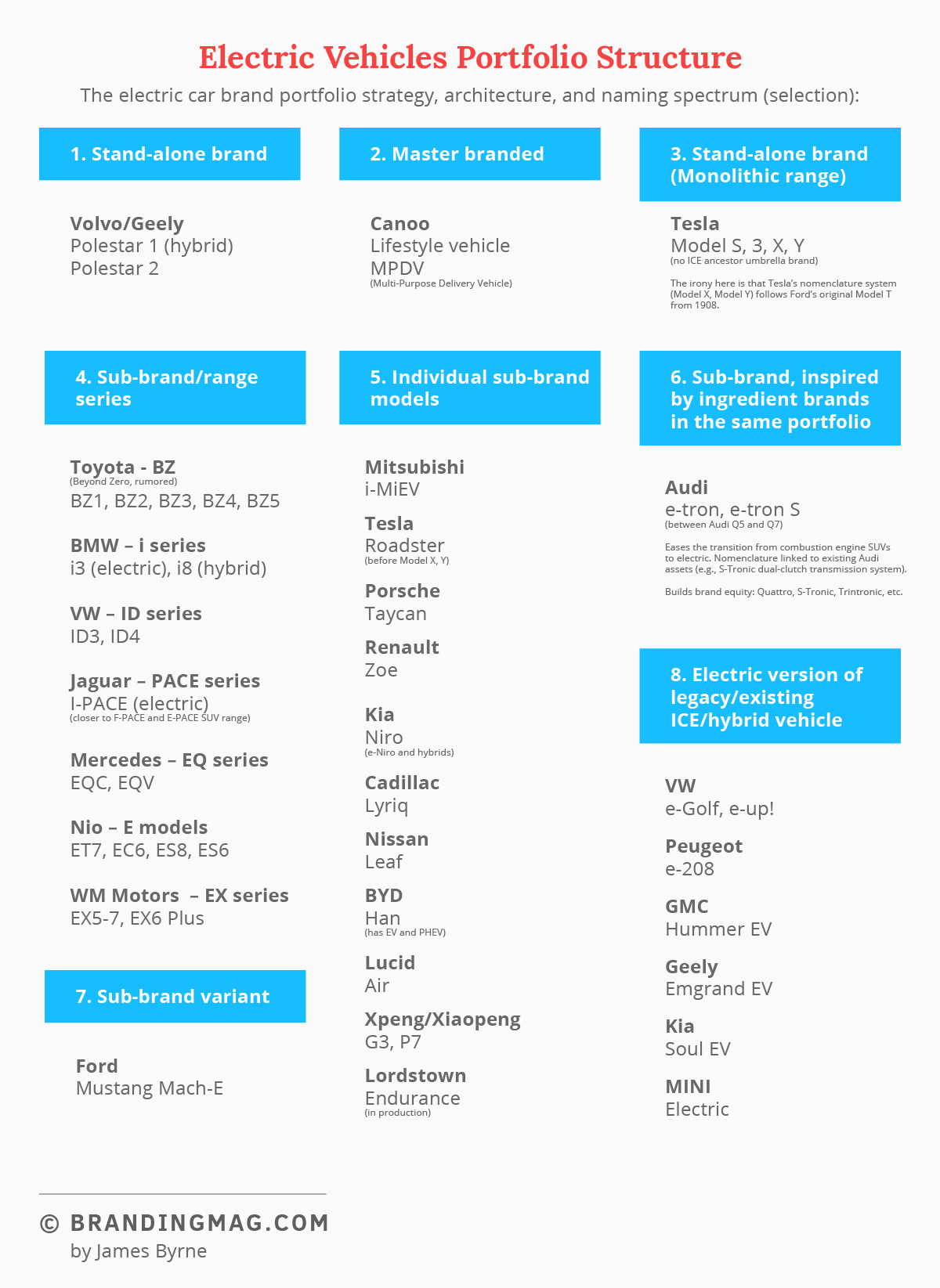

Brand portfolio strategy and brand architecture should offer flexibility to brand owners. Portfolio strategy should define roles for products, brands, and sub-brands. Brand architecture is the articulation of the relationships between products, brands, and sub-brands. Electric offerings are coming into portfolios alongside existing internal-combustion engine offerings, and, in many cases, hybrid combustion-electric offerings too (plug-in hybrid and self-charge).

The routes brands have chosen to take in respect to portfolio strategy and architecture vary, depending on a number of factors: when they were introduced, what else in the portfolio already exists/existed, and the connotations of those offers, and ambitions with the new electric launches.

As the old song goes – Old MacDonald had a farm – electric car models boast a pig’s stye of ‘E’s and ‘I’s.

The BMW i3 and i8 came along around the same time (the i3 launched in 2013) as Tesla’s Model S (2012) and looked visibly different from petrol car designs (especially the i3) deliberately standing out from the core ICE (internal combustion engine) range as a new electric offering, although the decision to use the ‘I-name’ system wasn’t particularly imaginative – taking inspiration from Apple’s nomenclature system (iPhone, iMac, iPad). Jaguar has followed suit with its I-Pace. ‘I’ means cutting-edge technology…but it’s confusing. Hyundai has its i-range – i10, i20, i30, and these are diesel and petrol engines as well as hybrids.

Other brands are using E instead of I. E makes sense, although it’s a little obvious. It’s short for electric in English and several other languages. We have already accepted into our vocabularies and dictionaries words such as ‘email’ and ‘e-cigarettes’, which are electric or electronic versions of their physical, manual, or combustion equivalents.

Many other brands have introduced a new range brand, or range series brand, which arguably could be considered a sub-brand – automotive brands are harder to classify than corporate brands or consumer packaged goods brands due to the complexity of the car design, spec, and additions/incentives.

Mercedes has just introduced its electric EQ series with the launch of the EQC SUV and EQV people carrier. The EQC is based on the X253 GLC-Class combustion SUV, and the EQV is based on the W447 V-Class. See how it’s confusing, when one of Mercedes’ core range brands is the C-class (mid-sized saloon car range)? In China, there are a lot of E-series model names – such as the Nio E models (ET7, EC6, ES8, ES6) and WM Motor EX series (EX5-7, EX6 Plus).

Toyota is rumored to have trademarked the BZ name as a range – for its electric models BZ1, BZ2, BZ3, BZ4, and BZ5. BZ stands for ‘Beyond Zero’. It’s a bolder move as a more stand-alone range brand, and Toyota has resisted generic naming such as I and E. There is a practical element behind the decision making too, though. Electric models require different wheelbase proportions depending on power output in order to make the car design more efficient – think BMW i3. That is why the Toyota (rumored) BZ will not look exactly like the RAV4, despite being modeled after it.

Audi has taken a different approach, introducing its e-tron range. While e-tron is a range brand, currently with the e-tron (an SUV in between the size of its combustion Q5 and Q7), and e-tron S (sporty version), e-tron is a sub-brand with flavors of an ingredient brand. The nomenclature is consistent with Audi’s S-Tronic automatic double-clutch transmission system, and its Tiptronic special transmission system. The word ‘tron’ is a consistent element as Audi builds its ownable brand equities with multiple elements – S-Line, Quattro, etc.

Ford has opted for the sub-brand variant route for its Mustang Mach-E range of currently three models.

Through the Mach-E marque, it looks to add more panache to the already strong Mustang personality and history, perhaps reassuring its power and sports credentials for any potential doubters.

Stand-alone architecture

Many players though are introducing new stand-alone sub-brands for electric offerings, from the smallest most accessible models such as Nissan’s Leaf, right through to Porsche’s prestigious Taycan. This approach is the most flexible, as there is no automatic wedding to combustion equivalents. The thinking from the brand owners is that if you’re in the know, and you want to know about electric models, you’ll seek out which models are electric.

That said, many brands are creating electric versions of existing combustion engine models. The same brand name with ‘E’, ‘EV’, or similar added to it. For example, the VW e-Golf, the MINI Electric, the Peugeot e-208, the Hyundai Kona Electric, and Kia Soul EV. Even General Motors has launched the GMC Hummer EV. This is done, presumably, where there is already a level of familiarity, reassurance, and comfort, or attraction and affinity with existing brands.

Mini has a huge history and heritage, that already made it an irreplaceable ‘lovemark’ – to quote Kevin Roberts – and its successful revamp in the noughties has only accelerated that love. So it makes sense that Mini would want to maintain that recognisability and brand affiliation. However, the Mini Electric might get confusing if Mini wants to then build various variants of the electric vehicle – think Mini Cooper, Mini Cooper S, Countryman, etc. This is why brand portfolio strategy and architecture are important. A similar argument exists for GMC’s Hummer, considered legendary in some circles.

However, less legendary brands do not need to emulate their combustion engine counterparts. Brand owners should question, “does my brand and model have a clear role within the portfolio?” If the answer is no, then the portfolio strategy should be revisited.

On the flip side, Polestar exists as a stand-alone marque, separate from Volvo ( its immediate parent) and Geely (parent of Volvo). Polestar 1 was a hybrid vehicle and Polestar 2 is fully electric. The brand has origins in racing teams, and a history interwoven with Volvo. But as Volvo, as a brand that stands for safety, and Polestar represent ultimate racing performance, it makes sense to exist as a stand-alone separate entity. A modern-day, electric-vehicle equivalent of the need to create a separate stand-alone brand that led to Toyota creating Lexus, Nissan creating Infiniti, and more recently Hyundai creating Genesis. Toyota, Nissan, and Hyundai represented everyday mainstream, and in order to reach the higher-end, luxury market, they needed to bypass those mainstream connotations.

Descriptors and ingredient brands

Of course, car brands also have descriptors and ingredient brands that can also convey drivetrain type and spec. Think of an Audi combustion engine. You might have Audi Q5 4.5(L) TFSI Quattro. Again confusing, at least to non-petrolheads, if you are using ‘I’ in electric vehicle nomenclature. TFSI stands for Turbo Fueled Stratified Injection. With combustion engines, electric, and hybrid cars, this can also be used to express what’s inside. For years, many Toyotas and Mitsubishi hybrids have had PHEV (Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle) branded on the backs of the cars as spec.

With new battery types, charging networks, and ranges becoming available, expect to see a new group of claims and specs on electric vehicles, with some B2B brands keen to getting their brand awareness out through their direct-to-consumer partners as ingredient brands (think Intel on Microsoft products). For example, Renault and Plug Power have a 50:50 venture – focusing on developing fuel-cell-powered vehicles and hydrogen turnkey solutions.

As technologies improve in battery technology, range, and infrastructures, expect more brand partnerships and new branded touchpoints in this area also. There will be more and more charging points separate from petrol stations and service stations. Shell has just bought Ubitricity, the leading charge point network in the UK. The eighth largest in the UK is Tesla’s own Tesla Supercharger network. Expect more battery brands to partner with car brands and energy brands in order to promote their technology. Those with credibility as “best in market” can become ingredient brands. The Pininfarina of electric. There will be more opportunities for brand associations through partnerships for battery and charging point brands. Imagine future equivalents of racing cars (e.g., the iconic Shell pecten on Ferrari F1 cars, Castrol logo on Nascar) albeit in more subtle ways – as battery and technology brands become more prominent ingredient brands.

Tesla has mastered the art of remote updating, so its cars are continually improved and updated in the same way Apple software is, without the need to bring the cars into service. VW also sees itself as a software company rather than an automotive brand at a corporate level. Daimler has entered into a tie-up with computer graphics specialist Nvidia for autonomous driving technology, and Aptiv has done the same with Hyundai (and branded it Motional). Expect to see tech ingredient brands emerging from these partnerships (like Siri from Apple).

On a more corporate brand and B2B brand level, we are already seeing platform brands emerge based on this world of electric and innovation. For example, BMW iVentures, The Toyota Mobility Foundation, Jaguar Land Rover’s Tacuna project, and GM Cruise (its self-driving platform).

Legacy and future

Porsche has gone all-in on electric with its Taycan, and it fits perfectly into the rest of its portfolio. Other supercar brands, however, have been more noncommittal on electric. While Ferrari has its hybrid SF90 Stradale, its CEO said last year he does not expect Ferrari to ever go full-electric. There is something in Ferrari engines and its history that means that 100% electric is not quite on-brand for the prancing horse. However, Ferrari could back and develop an electric supercar, but the brand might not be Ferrari as we know it.

It will be interesting to see how car brands introduce new electric vehicles as they become increasingly common amongst the traffic on our roads. In under 20 years, they are predicted to make up more than half of new cars sold. Will brand owners create more, new sub-brands, or will they continue to release electric versions of existing combustion engine sub-brands? The reasons for maintaining a sub-brand should be clear – it is a brand sufficiently loved and trusted by consumers? Does the design of the car itself reflect a progressive nature in line with the existing combustion engine equivalent? Can the new offers be introduced without creating a confusing portfolio of models while combustion engine models are still in circulation?

Brand owners can run insights workstreams to better understand consumer attitudes to buying electric and connotations of existing brands. But one thing is for sure: An exciting new electric car can easily warrant its own sub-brand, as Porsche’s Taycan has proven, and Polestar has taken that to the next level. And another thing is for sure, that the electric networks will mean brand portfolios will change significantly.

If we look far enough down the line, when electric cars are dominating the roadways, we might see nostalgia coming into play as brands seek to remind consumers of the days of combustion engines. Tesla’s nomenclature (Model X, Y) is already reminiscent of Ford’s Model T. As the quote dubiously attributed to Henry Ford goes, “If I’d asked people what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse.” Taycan means ‘soul of a spirited young horse’, comprising two terms of Turkic origin.

The future is electric. Or we should say, the future is not ICE. Hydrogen power is not yet competitive, owing to the fact that, in many countries, its network of stations is nowhere near as strong as it needs to be in order to operate nationally. Local and regional networks are starting to appear, but not yet national. There are a number of pluses to hydrogen fuel-cell power over electric battery vehicles. Hydrogen power is more sustainable than electric battery vehicles, it works better for larger vehicles (trucks, buses, etc.) and it works on existing drivetrains. Governments need to invest in and support hydrogen networks in order to make them a viable option. And when they do, they will be the ultimate eco-cars. And they will probably be stand-alone sub-brands too. The Toyota Mirai is already living proof.

Cover image source: John Holden