I traveled out of Nigeria for the first time in 2019, on a short business trip to Dubai–an experience that left me with a huge aftershock. Though a significant number of Africans (up to 8% of the total population) were living in Dubai, there was no African brand in sight. For a tourist destination like Dubai, one would expect to see at least one major brand from the second most populated continent in the world, but you move about the city interacting with so many global brands–apart from any major African ones.

This piqued my interest, and I have been restless ever since, struggling with the question: “Why are African brands not going global at scale?”

Tosin Balogun (a colleague of mine) and I originally hypothesized that a major issue with African brands is a limited understanding of how brands exist, grow, and expand. Based on our combined 2-decade involvement with local brand owners and a simple assessment of the curriculum of major business programs in the continent, we concluded that there is limited scholarship on the conversation of branding and building ambitious, larger-than-life brands in the region. Corporate Africa needed to be reoriented towards the most effective strategies to develop and expand ambitious brands capable of going global in our lifetime.

Recently, however, I had a chat with James Cornford (senior lecturer at the Norwich Business School) and introduced the question “why are African brands not going global at scale” to get his insight. James has vast experience working with global brands, and rather than provide me with a simple answer, he helped change my perspective on the entire question. I realized that applying the decomposition method used by computer scientists and engineers is the best way to answer a question as complex as mine.

Is it about our brands’ Africanness?

From James’s response, the first question African researchers, academics, and brand owners will have to answer is: Is our Africannes a barrier to global penetration? Are we creating brands that solve global problems or just African problems? Not sure if you’ve noticed, but most African products in international markets are packaged goods targeted at the global African consumer rather than global consumers overall. Which begs the question, as more Nigerians migrate globally (for example), are we creating brands to follow them abroad and keep them connected to their roots? Or are we interested in creating brands that are open, malleable, and adaptable to the local interests and nuances of global markets to attract a more global consumer base?

A quick look at the UBA UK website will show you that though the brand has an office in the heart of London, its interest is to simply facilitate trade between Africa, Africans, and the global market. Though there is a large banner of the London Bridge on the website banner, the statement on the website reads, “To be the conduit for international business to and from Africa.” Compare that to the banner on the J.P. Morgan Chase South Africa website, which reads, “We are committed to our business in South Africa, and we are one of the most prominent financial services firms in the country. From Johannesburg and Cape Town, we provide clients with products and services from across our asset management and corporate and investment bank lines of business. J.P. Morgan is a global leader in financial services, offering solutions to the world’s most important corporations, governments and institutions in more than 100 countries.”

You can clearly see the juxtaposition between J.P. Morgan Chase’s narrative in South Africa and UBA’s in the UK. Although J.P. Morgan originated in North America, it entered Johannesburg as a South African brand not as a North American brand helping the world do better business with North America. The statement positions them as a global bank, for the South African people. You could argue that the challenging experience of making financial transactions to and from Africa presents a unique opportunity for UBA to position themselves as a bank interested in solving this problem.

In their paper “The Influence of Global Brand Distribution on Brand Popularity on Social Media”, Kim. N.Y et al (2019) argue that global brands “are those with more than one-third of sales generated outside their home country, awareness beyond their home customer base…” If we’re concerned about African brands struggling to go global at scale, then it makes sense to begin by looking at their global branding strategies. This means interrogating their brand purpose or expanding it to be truly global, rather than having it simply represent a local brand with an international office.

Are African brands aspiring to enter through the wrong sectors?

When African brands attempt to go global, are we playing in global sectors? If yes, do we have a competitive advantage in the sectors we’ve chosen? These questions are important to answer because the quality of impact we can have in the global market is tied to the quality of influence we can bring to the global market.

In the context of economics, finance, and business, “global sectors” often refer to the major categories of the world economy in which businesses operate. These sectors encompass broad segments of the economy and help investors, policymakers, and analysts categorize and understand the economic activities of various industries on a global scale. One of the prominent sources that classifies industries into sectors on a global scale is the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS), which was developed by MSCI and Standard & Poor’s (S&P), Some of the primary global sectors include: Consumer Discretionary, Consumer Staples, Energy, Materials, Industrials, Healthcare, Financials, Information Technology, Real Estate, Communication Services, and Utilities.

As African socioeconomic and sociopolitical commentators, we talk a lot about our global presence and African renaissance, facilitated by African music, food, and fashion. While these are market segments in which we have distinct cultural differentiation and have been able to demonstrate impact on the global conversation, the functional mechanisms behind these segments are not areas in which we’ve shown significant strength. The truly global sectors that set the foundation for these expressions are still foreign.

Our true power and influence in penetrating global markets will become evident when we begin taking hold of any of the 11 global sectors. But first, we must think about which of the sectors we can own. Other countries and continents drive the world’s supply in some of these sectors, so in which of the sectors do we have the advantage? And can we displace the current leaders with our own scalable, global brands?

Do African brands have a global marketing capability issue?

Global marketing involves using marketing techniques and principles on a worldwide scale. It covers such issues as international promotion, international strategies, global finance, international government regulation, global sociological and anthropological targeting, and resource allocation. A quick search for an international marketing or global marketing course by an African university will give you insight into the huge knowledge deficit we have in preparing business leaders for global leadership.

We cannot solve problems we are not prepared for. Marketing and business management curriculum in our tertiary institutions need to be adjusted to accommodate the need for training globally-minded business leaders. We need more people that really think global.

In his 2018 paper entitled “On Globalizing Business Training in Africa: Toward a Theory of Business Education and Managerial Competence”, Vishwanath V. Baba argues that “in order for the curriculum to serve the needs of globalization well, one has to make all aspects of the classical curriculum sensitive to globalization theory through a process of infusion. This will result in a more contemporary management training where it becomes second nature for a student to interpret theories of business in the context of globalization.”

Have African brands missed the moment of globalization?

In my interaction with James Cornford, another subquestion we identified was: Is the African renaissance simply late? Those that have been following globalization conversation will have encountered, at some point, the saying that “globalization is dead”. I love the opening of Silvia Mărginean’s 2018 article “Globalization Is Dead: Long Live the Globalization!?”

“Globalization was the mainstream paradigm in the last 70 years, long enough to create and explain prosperity and welfare in a connected world. Recently, there are many signs that we are reaching a turning point. Globalization, as we learned about it in the 1990s, is based on three pillars: international trade, foreign direct investments, and ICT (information and communication technologies). The 2008–2009 crisis was a turning point for many things, including ideas and theories. During the crisis and also during the recovery, globalization was a central debate, for two reasons: some voices claim that the cause of the crisis is globalization and its rules and others say that anti-crisis measures and recovery are limiting the free trade, and foreign direct investments slow down because there is not enough capital available and the risks are too high, so the globalization looks to be in retreat.”

This highlights the possibility that our aspiration and goal to achieve global scale may be driven by the wrong perspective and timing. The war between Russia and Ukraine, the situation between China and the United states, Brexit, COVID, and other conflicting global issues are making the walls go up. The consumption of local brands is encouraged in nearly every country around the world. So, while our vision may be to leverage the impact of our soft culture power and pop culture influence to scale African brands to global dominance, will global markets be open and receptive to this ambition? Some countries have implemented protectionist policies, favoring domestic industries over foreign ones, like the Build America, Buy America Act. This could be a barrier for local brands looking to enter certain international markets.

Silvia Mărginean closes her paper with some hope for us:

“The world is changing, and we are confronting a new kind of globalization. First, this new globalization is still related to trade, but there are new and different patterns of trade: we are registering huge digital flows (old globalization was more about moving goods); the growth and competitive advantage for today’s companies are about complex value chains and about production processes sliced up in different stages and countries; and also, the flow of goods is changing – it is wider, and a higher number of countries are involved in the global processes.”

Is globalization only an African problem? Or is it a Global South problem?

This challenge isn’t exclusive to Africa; it reverberates across many regions of the Global South. By asking this subquestion, African business leaders can potentially draw parallels with their counterparts from other Global South territories, leading to a richer understanding of the shared challenges they face. It’s not that brands from the Global South haven’t made their mark internationally. Huawei, Jumia, Tata, and Embraer are testimony to the innovative prowess these regions possess. Nevertheless, scaling their presence in the global market has been a formidable hurdle.

Historically, many economies in the Global South (including those in Africa) have navigated a colonial past that cast long shadows over their present economic structures. Such histories often left these nations playing catch-up with the rest of the world, sometimes in terms of infrastructure, sometimes in terms of policy environments conducive to business, and often in terms of access to the kind of capital that worldwide scaling requires.

Financial constraints remain a significant barrier. While there’s no shortage of entrepreneurial spirit or ideas, there’s often a stark lack of resources to bring these ideas to the global stage–a reality compounded by supply chain complexities. When we begin to look at what other economies are doing to push their brands globally, we find lessons that are relevant for us in Africa.

Is the globalization of African brands a generational issue?

When discussing global markets, the key regions are often categorized based on their economic characteristics, geopolitical influence, and historical significance. These regions are: North America, Europe, Asia-Pacific (APAC), Latin America & the Caribbean, Middle East & North Africa (MENA), Sub-Saharan Africa, and Central Asia & Caucasus. Most times, an African brand hoping to go global will try to cross from Sub-Saharan Africa or MENA to North America, Europe, Asia-Pacific (APAC), and Latin America & the Caribbean. These regions may be enticing because they have the money we need and the consumerism culture to sustain international businesses, but a critical question arises: Do they possess the population that we can effectively target?

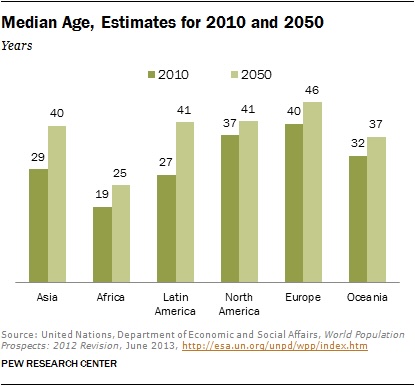

According to a study by the Pew Research Center on “Aging in Major Regions of the World, 2010 to 2050”, the markets we are targeting have a high old-age dependency ratio. This means that they have a population more concerned with pensions, healthcare, and retirement benefits. Brands that will be relevant to them will be brands that have locked in their loyalty over the years. These folks mostly lean towards brands they are familiar with rather than trying something new.

In their study of Older Consumers’ Adoption of Innovation in Japan: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Age, Emmanuel Chéron and Florian Kohlbacher concluded that age can affect innovation adoption. The study discusses how demographic variables, including age, can impact new product adoption behavior. This means that if our globalization efforts are aimed at trying to sell to the West, we must remember that they won’t be too open to trying new brands given the ratio of young to old people.

What’s the point of all this?

This article, unlike others I have written, wasn’t intended to provide answers to the question “Why are African brands not going global at scale?” Its purpose is to encourage us to reframe our thinking by exploring other questions that can guide us in unlocking the right theories and evolving the right strategies for expanding African brands globally. It is also meant to help us adjust our visions, ambitions, and expectations as we continue engaging the world in an attempt to build truly global businesses.

Cover image: EvgeniiasArt