In this, the sixth installment of my Brand Strategy Spoilers series, I unpack the decision-making factors that explain shopper and consumer behavior–specifically, the four drivers of behavior and the five barriers that hinder decision-making. These factors are based on a wealth of knowledge from the world of neuroscience and psychology.

Together, these foundational why’s provide the tangible framework with which to reliably assess what’s really driving your business, what’s hindering your results, and what you can do to dramatically influence behavior out in the real world. And this installment touches the veritable third rail in marketing boardrooms and analyst notes the world-over: price.

Here are the facts: Everything is getting more expensive, and headlines remain awash in the consumer response to climbing prices. But where most are getting it wrong lies with the highly conventional assumption that as prices go up, consumption goes down. This traditional view of behavior elasticity is flawed.

This is not just theory; it plays out in the data. Particularly for categories like food and beverage, conventional price elasticity models have proven inaccurate in predicting consumption behaviors. This is in part due to the cathartic impact of the pandemic, but even in recent years, put plainly, consumers are buying more things (even as prices rise) than the number-crunching anticipated.

Why? Simply, because even a factor as seemingly straight-forward as price is highly emotional in the hearts and minds of consumers.

In fact, it’s not even accurate to lump “pricing” into one bucket, as people perceive the price of goods and services via distinct mental lenses. Looking at years of longitudinal data, neuroscientist T. Sigi Hale PhD and team have identified a deeper understanding of price perceptions as prices have continued to climb.

In short, when a person considers the price of something, they ponder specific questions deep in their subconscious mind:

- How much of a hassle will it be to determine if this is a good price?

- Is the price of this unfair or unjust?

So, when shoppers are looking at the price tag, they’re not actually looking at the price itself. They’re weighing the “cost” relative to the price. And herein lies the unlock for marketers attempting to navigate these treacherous waters.

Let’s start with what NOT to do. Because of the decision-making dynamic I described above, simply lowering the price alone won’t work. Why? Because when a shopper encounters a lower price, deep in their subconscious they’re thinking…

- Oh great, more hassle to figure out whether this is a good deal.

- Is this a trick? Is this price fair?

Not to mention the fact that, generally speaking, racing to the bottom on price promotions is low on the list for most brand, retail, and revenue growth leaders.

So, what should be done? In order to navigate consumer perceptions on pricing, marketers should assuage these subconscious concerns via three principles:

- Minimize the cost-behind-the-price

- Eliminate mental math

- Assure fairness and justice in pricing.

These are the ways to reduce the perceived “cost” in the hearts and minds of shoppers, and they’re instructive in guiding pricing strategy well beyond mere price.

Cost-minimization principle #1: Minimize the cost-behind-the-price

The principle here is that the hassle of figuring out prices is actually more emotionally costly than paying the prices themselves.

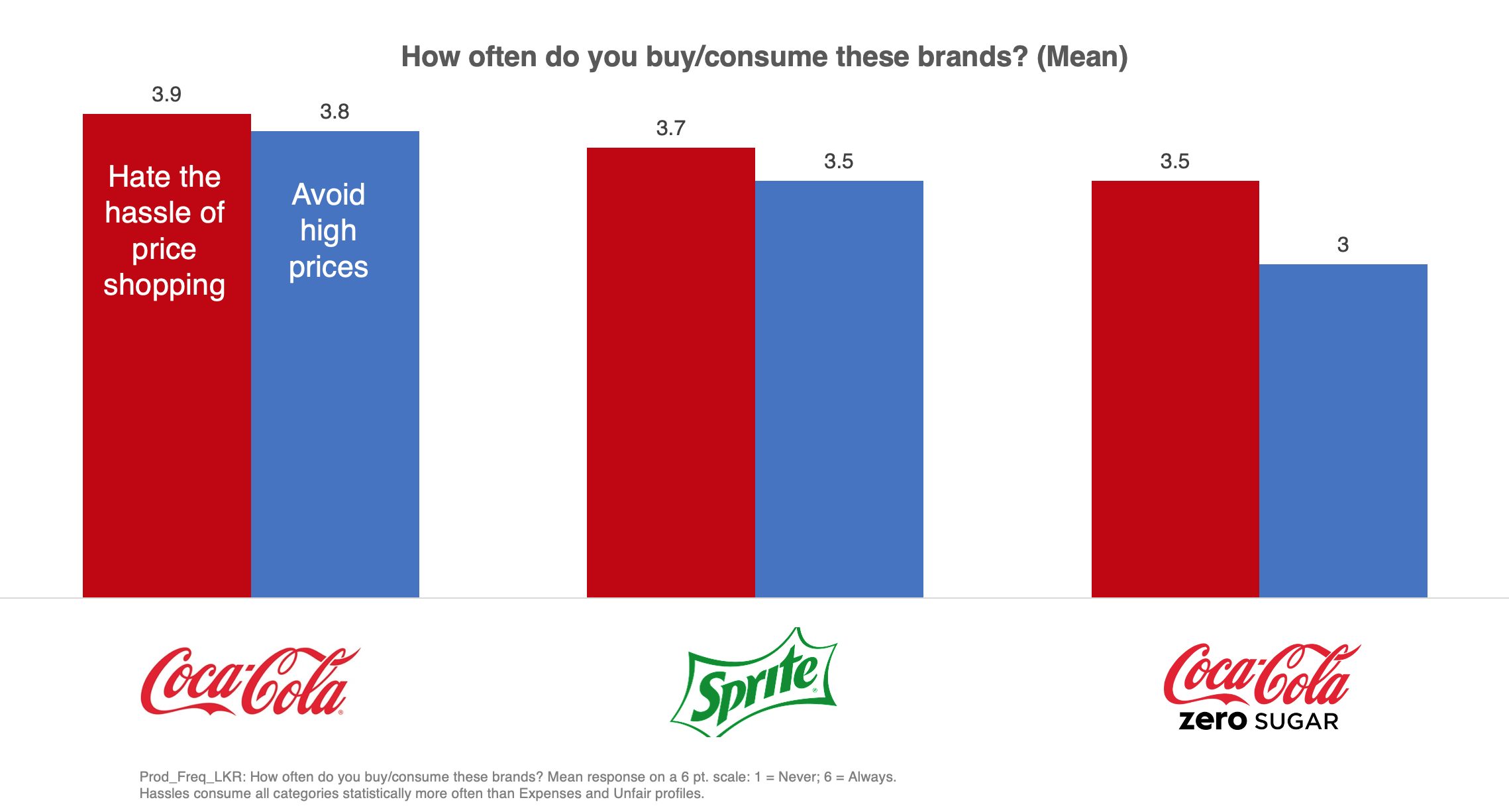

Looking at a familiar portfolio of soft drinks demonstrates this dynamic in action. Below is a table from a unique database of consumer sentiment, curated by Hale and team. This combines usage of these brands, with the cost consumers feel most strongly.

This assessment is measured in a unique way, capturing self-perception of usage. So, in the above, a person who consumes Coca-Cola frequently (1 = “never” consume, 6 = “always” consume, so 3.9 represents regular / frequent usage) is most hindered by the hassle of price shopping (the red). Whereas someone who consumes it slightly less is hindered simply by high prices (the blue). And the gap is wider for Sprite and Coke Zero.

This demonstrates that, for Coke’s most valuable consumers, the hassle of price shopping–comparing prices, looking for the best price across retailers, and so on–is actually their biggest barrier. The mental work required is the core of the perceived ‘cost’ even more than the price of the soda itself. Which leads to the second principle.

Cost-minimization principle #2: Eliminate mental math

Think of mental math as the accounting required to “solve for” the amount of savings, which is frustrating to the brain. Consider the example below: On the left you have some promotional prices for Coke and Sprite.

But just look at all the math! 12pk/12 fl oz, save $1.46 when you buy 3, $4.33 or $5.79 each.

Huh?

Now, cut to the real world of the shopper: This person makes purchase decisions and brand choices in nanoseconds. The byzantine equation outlined above is effectively meaningless. What’s going through that shopper’s mind is a mash-up of confusion and frustration.

The psychology discipline of heuristics–the decision-making shortcuts people use to navigate daily life–provides at least one remedy in the form of the “framing” heuristic.

In short, framing means breaking down larger amounts into smaller, incremental amounts to make the cost more transparent. In the example above on the right, the benefits of the framing heuristic become obvious. This takes the consideration from an MIT-level math equation to a simple statement of price. Less frustration, more purchase behavior. Even when the price itself may actually be higher, the perceived cost is likely lowered in the form of removed frustration for the shopper.

Cost-minimization principle #3: Assure fairness and justice in pricing

Recent years have created a high level of stress in general. People are experiencing an ambient level of anxiety, and many trusted conventions have been challenged by everything from the pandemic to inflationary pricing. One result of this ongoing stress is a level of mistrust. Is this price higher so the CEO can buy another vacation home? Am I getting the same deal as my neighbor? Is this company / retailer trying to manipulate or trick me?

This concern of “unfairness” directly impacts emotional perception when it comes to considering the price of a good or service. If a price is perceived as unfair or unjust, the actual price doesn’t matter.

Think of the last time you paid $5 for a bottle of water at a pro sports stadium. They had you cornered, so you paid the exorbitant price, but you’d never willingly repeat the behavior and certainly weren’t pleased with the transaction. And it’s not so much the $5, but rather the principle of being taken for a sucker.

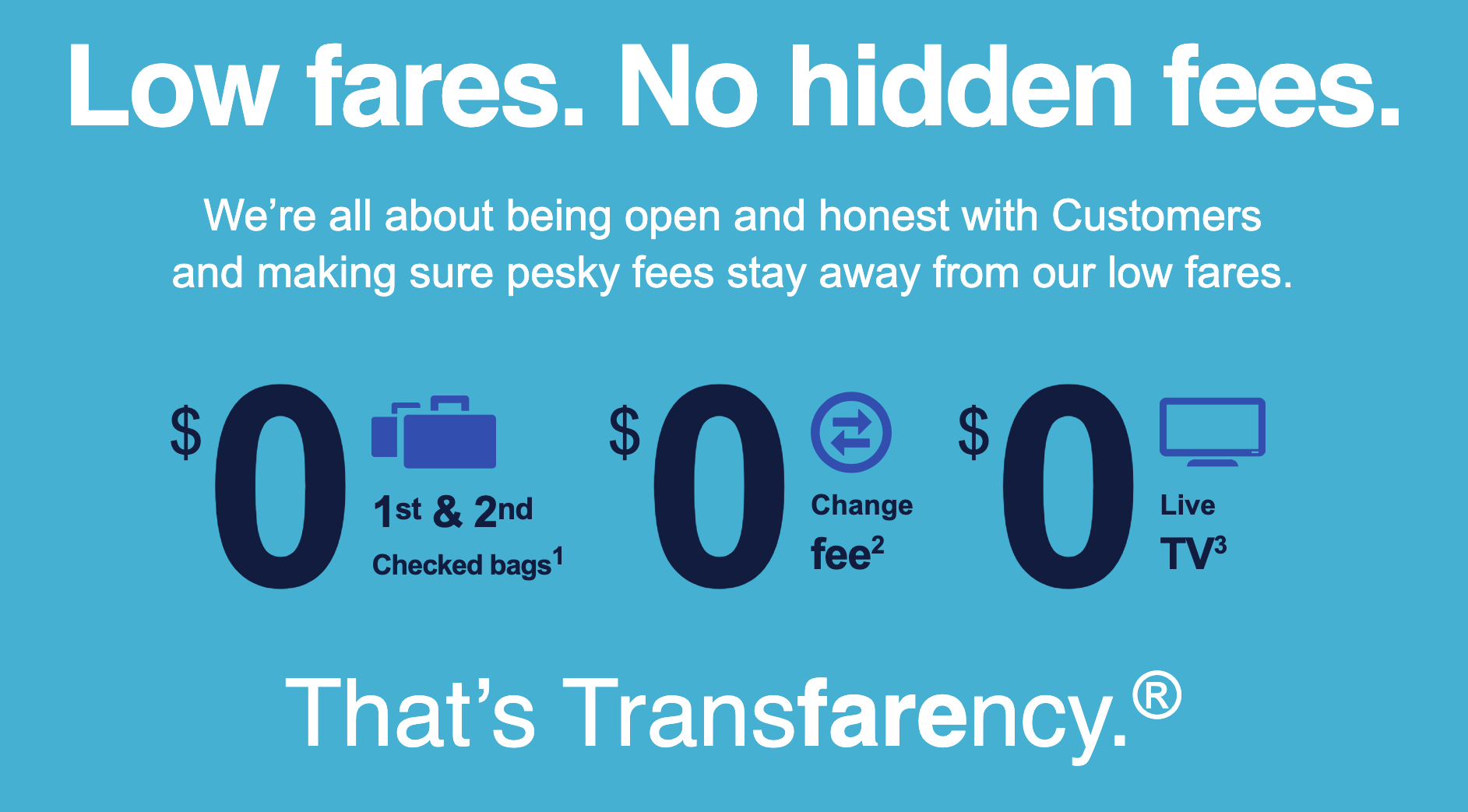

Southwest Airlines is a “discount” carrier that provides an excellent example of framing value via this cost perception. They’ve built their value proposition not merely based on “low fares” but rather on transparency and fairness–going so far as to trademark the strapline “That’s Transfarency”.

As a result, the brand consistently beats “non-value” carriers like Delta and American Airlines on guest satisfaction and loyalty. In other words, passengers think the airline provides a better experience, not just a cheaper one, all thanks to the perception of fairness and justice in their pricing.

So, as your teams ponder inflationary pressures, shopper leakage, trade-down / trade-out, and the gamut of price-driven business concerns, remember that it’s not always really about the price. It’s about the cost.

Cover image: ArtFamily