This article follows from the previous two articles in my Brand Campaigns series, where we analyzed the commercial impact of Apple’s “Think Different” brand advertising campaign. If you haven’t done so yet, I recommend starting at the beginning (Part 1) or, at the very least, reading Part 5.2 before continuing.

Now, for a brief recap of what we found out so far…

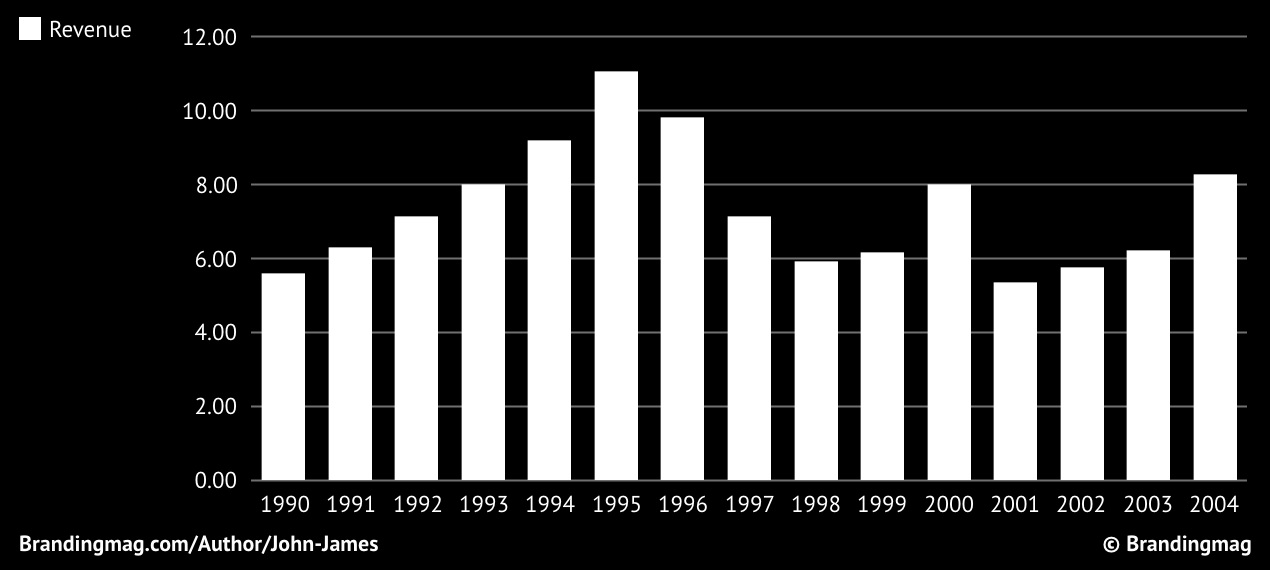

Did revenue increase?

The “Think Different” campaign ran exclusively as part of Apple’s 1997-1998’s advertising strategy, which had a $90mil annual budget. After 1998, the campaign continued in a supporting role alongside other campaigns until 2002. Apple’s revenue remained reasonably flat from 1997 to 2003, apart from a bump in 2000, with a noticeable increase only starting in late 2003 and 2004, nearly a year after the campaign ended. However, many commentators attribute this rise to a delayed impact from the brand campaign.

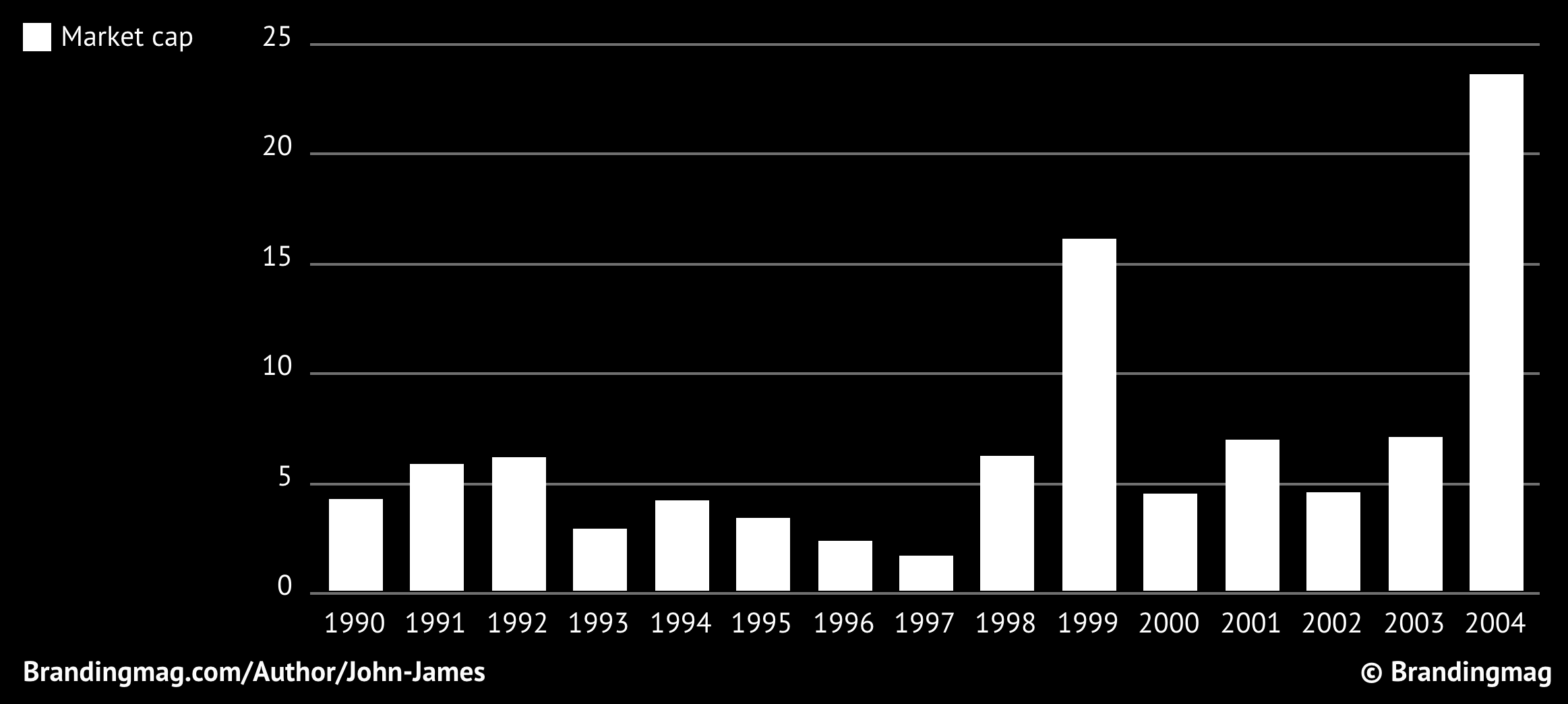

Did company value increase?

After a steep three-year decline in company value leading up to Steve’s return in 1997, Apple experienced a reversal. However, many companies in the tech sector also benefited from the widespread halo effect (the Dot-Com boom). This helps explain the extreme highs, leading to a peak in 1999.

Following the Dot-Com bust in 2001, the market cap declined and Apple didn’t see significant growth until 2004—a moment that aligns with another pivotal event, which we will explore further shortly.

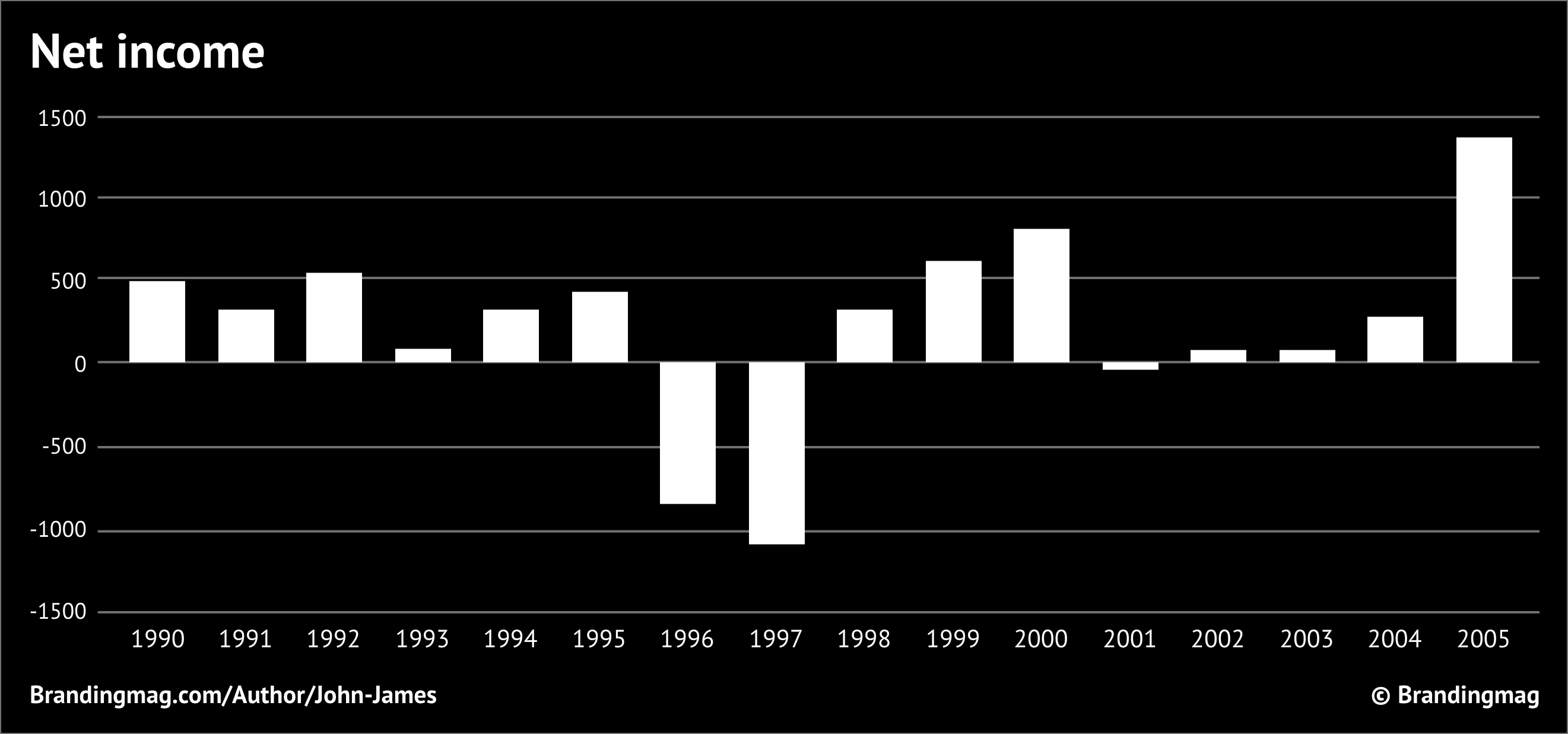

Did profit increase?

Apple saw a modest increase in their profit during the first three years of the “Think Different” campaign before retreating again. However, these gains appeared to have stemmed from substantial cuts to expenses, rather than any significant increase in revenue. Apple also reduced the prices of their new product range after identifying pricing as a key factor for poor sales. Therefore, the argument that this brand campaign somehow reduced price sensitivity and led to an increase in contribution margin and net profit is a weak one.

Did market share increase?

We didn’t examine market share in Part 5.2, but it seems there was no significant increase. Apple’s share of the personal computing market rose slightly to 4.1 percent by the end of 1997, but it hovered around 5 percent for the remaining years of the campaign (1998-2002).

Some major critics argue that the “Think Different” campaign actually hindered growth. They believe it focused the brand toward a niche audience rather than appealing to the broader market—a claim supported by empirical brand research.

“The hype about differentiation and positioning can easily lead to the conclusion that brands need to be strong on one or two CEPs to be successful. This ignores the important (empirical) fact: large share brands are linked to a broader range of CEPs (Category Entry Points) than smaller brands. This breadth of memory structures is a key part of their equity. If you want to create a big brand, you need to link the brand to the many different CEPs in the category—not just one or two.”

– Jenni Romanuik in How Brands Grow, Part 2

In Part 4 of my series, I discussed how one of the key strengths of a successful brand campaign is recognizing that growth depends on appealing to all buyers in the category including light-buyers—not just niche segments or die-hard fans. For Apple, this meant reaching all buyers within the personal computing market, not just those who were willing to buy into the ideal of contrarianism. Steve Jobs’ former publicist, Andy Cunningham, explains her view on why Steve chose to pursue this path.

“I think it was the Think Different campaign that took it from a downhill slide to an, ok, now we’re going to go on up. That is Steve’s greatest gift. is that he’s incredibly emotionally intelligent. He understands what people want before they do. He understands what people are going to do before they do, And that’s what he capitalized on when he came back with the Think Different campaign. So now he realizes, ok we have a cult here. Let’s protect that cult. Let’s feed that cult and see if we can get it to grow.”

– Andy Cunningham (Steve Job’s former publicist)

Arguing that creating cults are growth restrictive is a valid argument, as large cults are rarely seen. To grow, a cult must go mainstream and then, by virtue, it stops becoming a cult. Creating a cult is always a short-term, challenger brand pursuit. This is something well understood by those working on McDonald’s advertising campaigns.

“The brand’s associations and tentacles are just too big to make it stand for this one thing over there, and everything has to point to that [one thing].”

– Tass Tsitsopoulos, Planning Director at Wieden + Kennedy

The “Think Different” campaign might have been an effective way for Apple to reset its brand image—an initial step to clear the deck, stabilize any decline, and pave the way for the future. However, if we look at it through the lens of brand growth, Apple’s brand didn’t grow much, if at all. In fact, growth was doomed from the start by virtue of the creative idea!

This might explain why the “Think Different” creative theme was never repeated or iterated upon. Despite its popularity within industry circles, it ironically constrained the one thing they wanted to happen—growth!

So, if the campaign wasn’t responsible for their future success, what was?

Products FTW

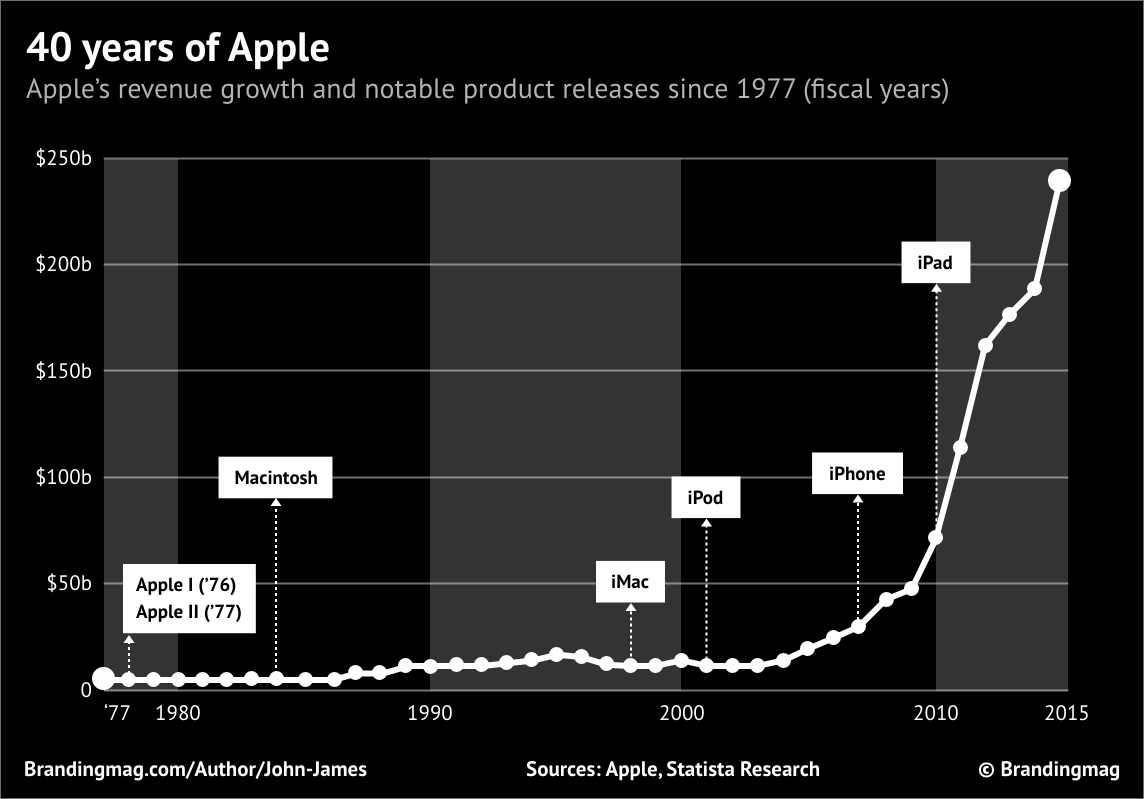

Contrary to what many marketers might claim, the product “P” of marketing was the most significant contributor to Apple’s commercial growth—not brand advertising, or any advertising campaign for that matter. And during the period we are most interested in (1997-2007), the iPod was the main catalyst.

That doesn’t mean we ignore the supporting role advertising played in contributing to Apple’s commercial success. However, advertising-biased marketers will routinely ignore the role products themselves play as the primary driver of growth. Just listen to what Steve says about the product here:

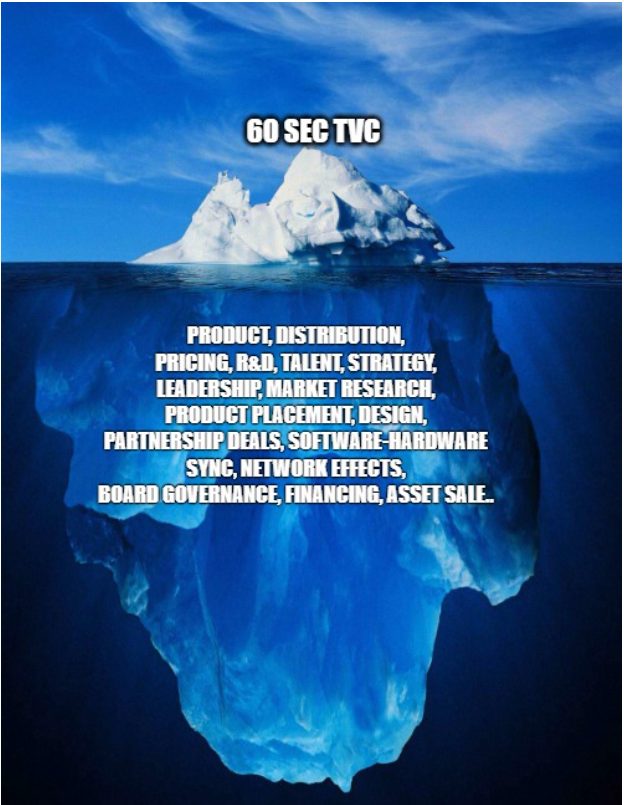

The importance of a product is something well understood by tech founders. Product-market fit (PMF) is a strong theme within the software-as-a-service (SaaS) growth community; however, in traditional business sectors (especially B2C consumer packaged goods), decades of departmental siloing has pigeon-holed marketers into pure communications roles. This leaves them unexposed and detached from pricing, product, distribution, and owned/earned media—some of the most powerful growth levers any business can invest in.

Marketers also forget that product experience is the ultimate test for all upstream advertising, especially brand advertising. It doesn’t matter how good your ad is, how many awards you win, how many pats on the back you get from colleagues, or how popular your content is on social media. You can’t “build a brand” if the product fails to deliver on the promises you’re making. And when you’re promising customers they’ll be able to “change the world”, that is an enormous promise to deliver on.

Rocketship iPod

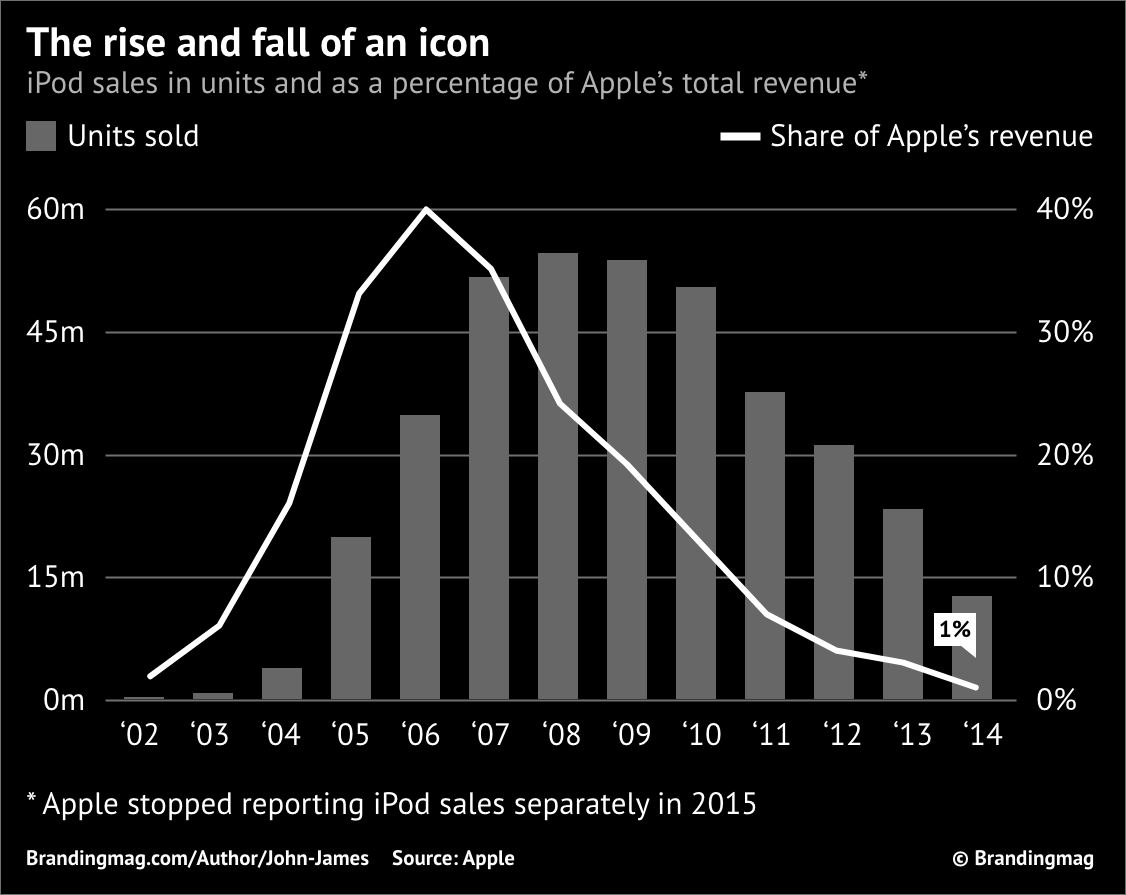

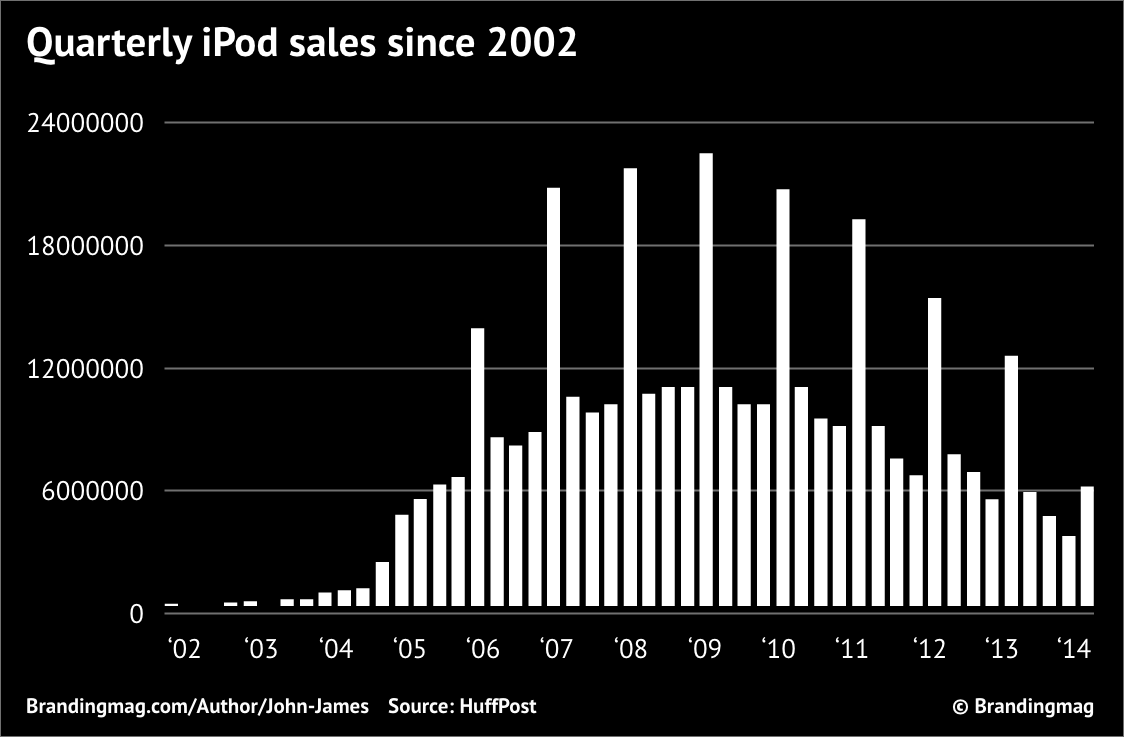

To understand how explosive iPod’s growth was, take a look at the following figures: Sales skyrocketed from 400,000 units in the first year (2002) to 4.4 million units in 2003 and over 20 million units by 2005. By 2006, the iPod was accounting for 40% of the entire company’s revenue!

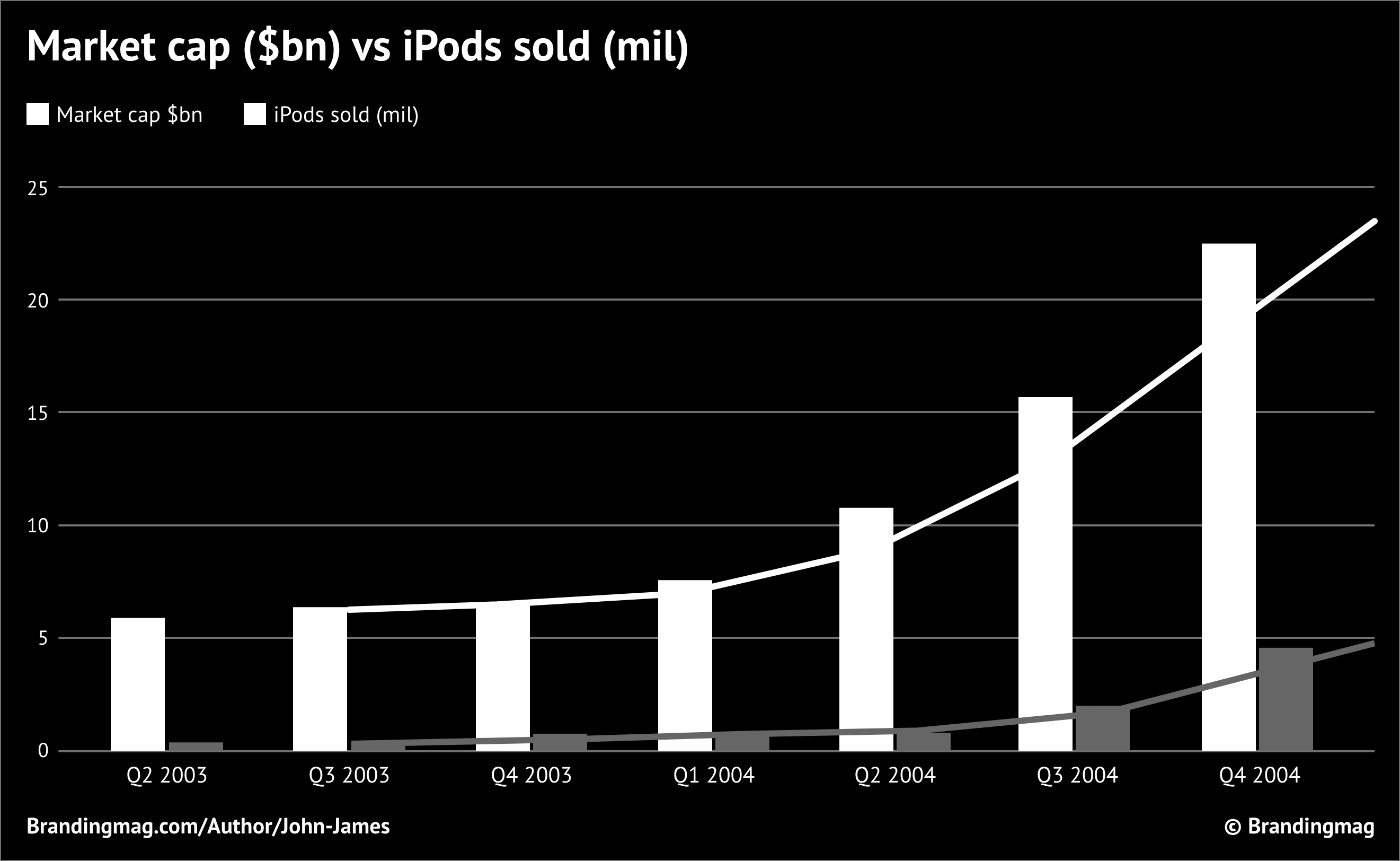

If we break this down by quarter, you’ll see a clear pattern emerge leading up to the stock’s breakout moment. In just four short quarters, Apple’s public market value quadrupled.

Investors and analysts love seeing rapid growth, especially the start of nonlinear, quadratic S-curves (see below). These product S-curves are considered reliable indicators of future earnings. And when Apple went from selling tens of thousands, to hundreds of thousands, and eventually to millions of iPods within just a few quarters, you best believe the stock market responded enthusiastically.

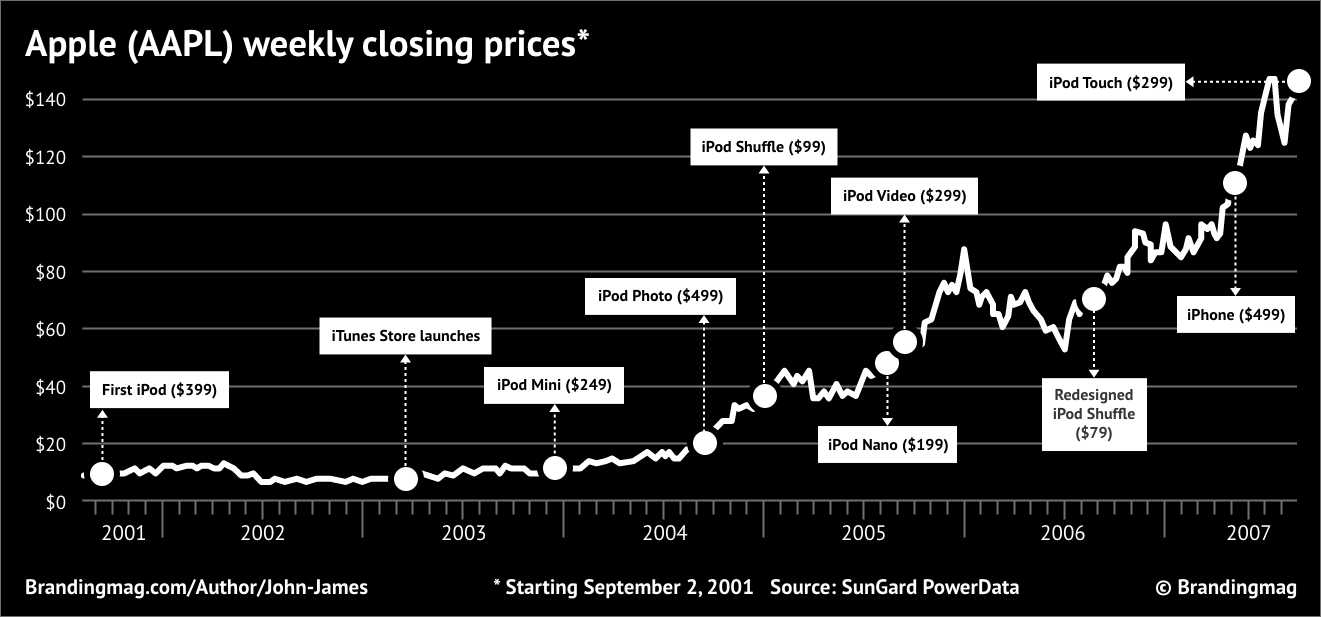

It’s important to remember, there wasn’t just one iPod. Many individual products, including iTunes, were released prior to the iPhone in 2007. Notice the different price points, too. The iPod nano, for example, was priced at roughly half the cost of the original, and Shuffle was half that again. This extended iPod’s appeal to a far broader market than would otherwise be the case.

The iPod was actually many people’s first Apple product and helped seed all future sales, including the iPhone.

The iPod’s success helps explain the massive rise in Apple’s market value starting around 2004-2005. A relationship that seems to be far stronger than anything we could find when analyzing their advertising, especially “Think Different” (which had ceased airing years before).

Product ecosystems and network effects

Even more impactful was how iPod initiated the creation of one the most powerful business growth levers there is: network effects.

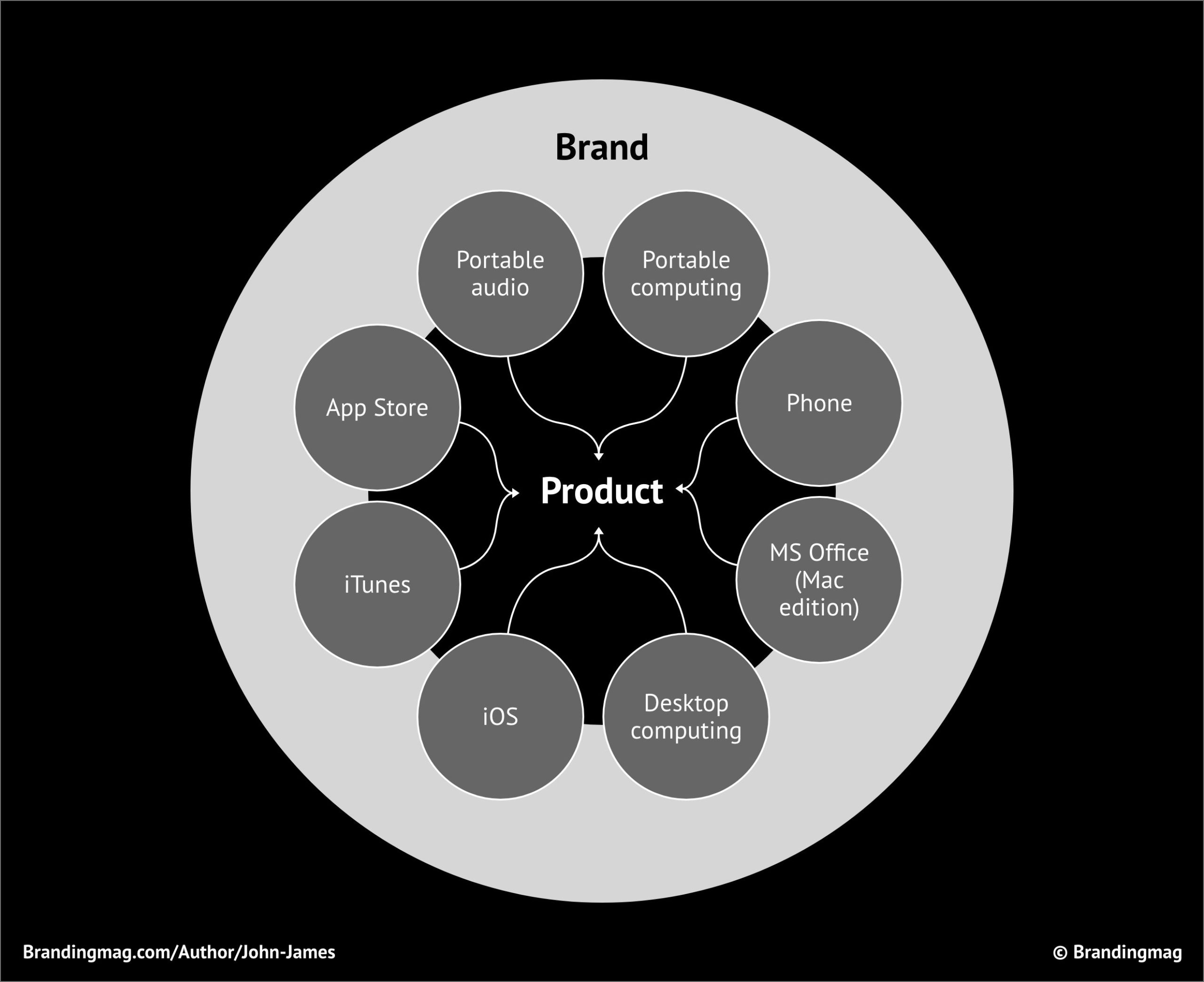

The iPod and iTunes took Apple from a company only known for personal computing and expanded the brand into new categories (entertainment and wearables). In Apple’s case, network effects started to take hold with the creation of what’s called a product ecosystem. This is where total customer value is increased beyond the sum of the parts—the more products customers buy, the more value they reap.

If you’ve used Apple products before, you’ve likely noticed how seamlessly they all sync with each other, and how poorly they sync with competing products. This is intentional. It encourages customers to remain loyal by buying multiple Apple products. Apple’s product ecosystem provides superior customer value, while at the same time, creating significant barriers to switching.

By the early 2000’s, Apple was rapidly evolving from a personal computing company into something much more, thanks to iPod and iTunes. The release of the iPhone in 2007, along with the launch of the App Store, increased this market once again. Apple’s walled-garden, hardware-software ecosystem continues to be a central part of the company’s growth strategy today—and one of the key reasons Berkshire Hathaway is such a fan of the stock.

“In business, I look for economic castles protected by unbreachable ‘moats’. I don’t mean big moats like China’s Great Wall… What I look for is any kind of barrier that keeps competitors from taking away market share.”

— Warren Buffet

Marketing myopia

Koen Pauwels highlights how easy it is for marketers to misattribute periods of company growth by fixating on communications campaigns exclusively.

“When teaching the iPod case, I always talk about how the ‘Silhouettes’ campaign coincided with (1) making the iPod PC compatible and (2) iTunes, which are likely much more important [to their growth story].”

— Koen Pauwels

Yet, within the marketing industry there seems to be a strong tendency to attribute cherry-picked campaigns to periods of business success, rather than recognizing it’s part of a much bigger picture. This oversight may be a byproduct of the advertising agency era where marketer’s spent most of their time and budgets on promotions and ad campaigns. There is also a tendency for marketers to ignore the product experience, opting instead to focus on “building the brand” by exposing aspirational ideals. However, even those working in agencies are getting sick of this and finally speaking out.

Getting the basics right

That rabbit hole aside, before we judge success factors from afar, I think it’s important to understand the context of this time first.

Many people forget that Apple’s marketing fundamentals were very poor before Steve Jobs returned. They had an abundance of products which were poorly positioned and overpriced. They didn’t have a great distribution network, product innovation was stalling, and management seemed to be resting on their laurels while market share gains from their first-mover advantages in the 80’s were being steadily eroded by IBM and Microsoft. This is a situation strategy expert Richard Rumelt clearly recalls Steve mentioning when they spoke in May of 1998.

“The product lineup was too complicated and the company was bleeding cash. A friend of the family asked me which Apple computer she should buy. She couldn’t figure out the difference among them and I couldn’t give her clear guidance, either. I was appalled that there were no Apple consumer computers priced under $2000. We are replacing all of those desktop computers with one, the Power mac G3. We are dropping five of six national retailers—meeting their demand has meant too many models at too many price points and too much markup.”

— Richard Rumelt in Good Strategy, Bad Strategy

Listen to how much Steve focuses on everything BUT advertising in the first 3 minutes of this video. The start of a famous clip, which curiously doesn’t make the cut of the version passed around on social media, can be found here.

The start of a famous Steve Jobs’ speech that’s omitted by marketers. Part 5 of the article series dropping soon! pic.twitter.com/j9sNJd1yCj

— John James (@adoseofjohn) October 30, 2023

Additionally, they had a team focused on process instead of content (aka, creating value). This bureaucracy was limiting their growth potential and keeping the company in a holding pattern.

Campaign conception

Curious omissions like these facts above were just one of the many things that surprised me while researching this campaign. And figuring out exactly how the “Think Different” campaign came about was more difficult than I anticipated. There were numerous contradictory points of view floating around, and everyone had their own version of events.

If you’ve been involved in a successful marketing campaign before, you’ll probably understand why. Once something becomes a success, it doesn’t take long for an army of gophers you didn’t even know existed to emerge. All eager to associate themselves with the initiative and claim credit, often spinning their own narratives.

But after some digging, one thing became clear pretty quickly. Contrary to what Steve himself said at times, “Think Different” was not a master-planned campaign commissioned by a visionary CEO. It was actually a reluctant choice by someone under pressure who had a soft spot for his former agency. Luckily, it just happened to become famous and advanced the careers of everyone involved.

Here’s how “Think Different” really came about to the best of my knowledge.

Return of the Jedi

Apple was a former client of TBWA/Chiat/Day before Steve’s departure in 1985. They helped create another “successful” advertisement called “1984”. But with Steve Jobs now gone, John Sculley switched agencies to BBDO shortly thereafter. And BBDO were the incumbent before the global account was put out to pitch in 1997 just before Steve’s return.

When Chiat Day heard Steve was back and the account was out to pitch, like any sales-indeed team, they quickly seized the opportunity. Luckily, executives at Apple already had a mandate to consolidate what had become an overly complex web of agencies around the world. As we all know, Steve had an affinity for simplicity, too. He preferred a simpler, streamlined operation with fewer vendors, especially during times of financial strain. Familiar faces that can be trusted never go astray when you’re looking to shore up political support. So, this was the receptive atmosphere TBWA/Chiat/Day were walking into in late 1997.

Although the final campaign was a collaboration of many minds, “Think Different” was arguably first conceived in raw form by Chiat Day art director, Craig Tanimoto. There was no formal brief or big strategy document with proper diagnosis backed by research—it was based on some early concept sketches Craig had completed, combined with a gut feeling Apple was a brand for people who thought differently.

The creative idea was straightforward. It was based on an assertion that people who have made significant changes to the way the world works are often considered outsiders or contrarian thinkers. Steve himself was an outsider, too, if you look at his early years, so it’s no surprise this creative idea eventually resonated with him personally.

The “Think Different” moniker also doubled as a counterpoint to arch rival IBM’s “Think” campaign, which was also running at the time. The creative strategy was simply inversion mixed with hard positioning with an appeal to competitive egos. Egos, logos, and pathos. The concept was simple and effective. Armed with this idea, the agency set up a meeting with Steve and pitched the idea in late 1997.

And he absolutely hated it.

“…he [Steve] was far from the mastermind behind the renowned launch spot. In fact, he was blatantly harsh on the commercial…“The crazy ones” script I presented to Jobs, as well as the original beginning and ending of the celebrated script, all ultimately stayed in place, even though Jobs initially called the script “shit.”’

— Former ad executive Rob Siltanen.

So, not only was the campaign not Steve’s idea, he didn’t even like it. However, I suspect three key points changed his mind. If you’ve read Part 4 of my series, where I discuss the pros and cons of brand campaigns, you should be familiar with most of these.

Convincing point #1: Product void

By late 1997, Apple had just cut several products and had no new releases planned for the next 10 months. They also had a ~$90m ad budget which needed to be spent, but they had nothing specific to advertise! And Steve wasn’t keen on promoting the work of his predecessors—many of whom were responsible for his exit. He likely preferred to avoid promoting products he planned to replace.

The reason “Think Different” doesn’t feature any products was a practical decision more than any deliberate pure brand campaign play. This point is especially important to note if you’re someone who believes brand campaigns shouldn’t feature products. We learned in Part 3 that here’s no reason not to because, in order for advertising to work commercially, it needs to form memories attached to a specific product category.

The notion that brand campaigns shouldn’t feature products is perhaps one of the most destructive influences this campaign has had on the advertising industry. Because in an effort to emulate Apple’s advertising prowess, people have misread this practical choice as a quality benchmark for brand campaigns.

“The way most people think about a brand campaign is, an intense marketing effort. Usually supported by a large media spend, and a bunch or TV ads or something like that, that doesn’t talk about the product. That’s actually how most people would define a brand campaign versus any other kind of marketing campaign… [so] what we’re playing with is this idea of the lofty brand campaign which is somehow emotional, aesthetic, and usually bereft of product or features – but full of ‘Feeling’.”

— Ethan Decker

Convincing point #2: Internal marketing

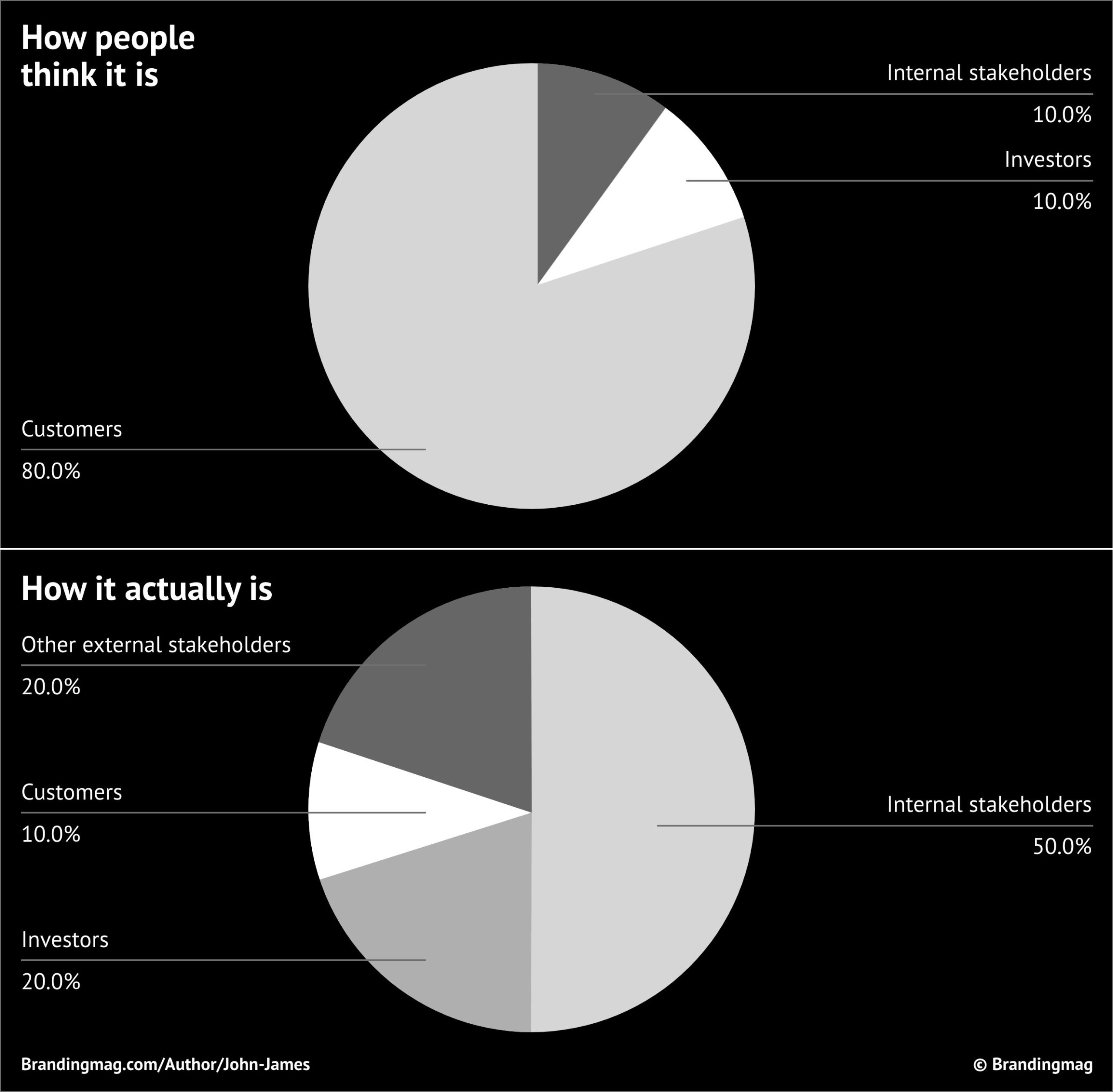

We can’t overlook the fact that a significant proportion of marketing efforts these days aren’t targeted at customers—and this is especially the case with brand campaigns. Company stakeholders include investors, the board, management, employees, partners, regulators, journalists, prospective employees, and more. For larger and more complex companies, addressing all these audiences becomes more critical.

Have you ever seen an ad and thought to yourself, “That was a terrible ad; they don’t even understand why we buy their product”? This might be why.

In Steve’s speech, he mentions that the brand had suffered from neglect, and the campaign was a way to restore it. He notes that staff were unaware of what Apple stood for and the direction in which it was going. So, “Think Different” was as much about communicating the company’s mission and vision to internal stakeholders as it was for potential consumers. It was a rebranding effort that spoke to both internal and external audiences. Moreover, if this turnaround was successful, the company would have to hire more employees—especially after laying off 4,300 of them. What better way to encourage political support, educate employees, and project confidence than with a $90m+ brand advertising campaign?

Anyone who has worked in senior marketing positions will recognize the graphs below to be true. This highlights the danger in emulating brand campaigns like “Think Different” and assuming they are effective at acquiring customers, generating revenue, and growing the brand.

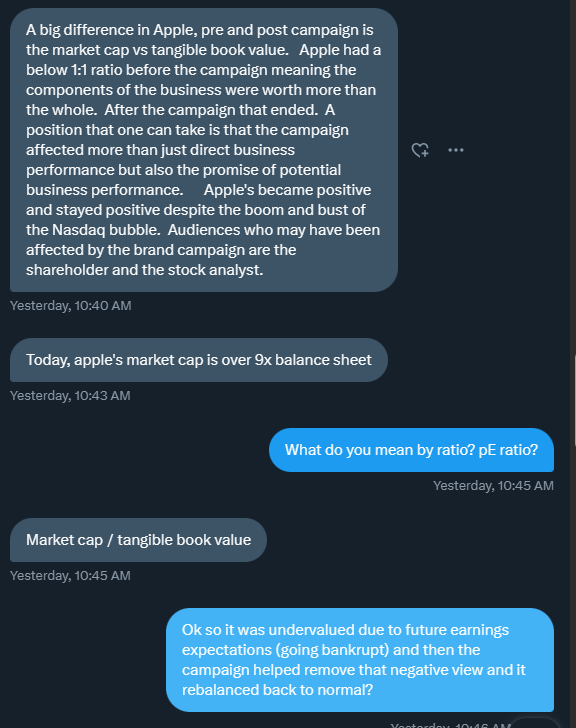

Convincing point #3: Finance

Edgar Baum, a brand finance expert, explains how the “Think Different” campaign likely focused on influencing the finance community (see conversation below).

For clarity, a price-to-earnings (PE) ratio is a rough measure of how expensive a stock is relative to the company’s earnings, whereas book value is “the value of the company according to its books (balance sheet) once all liabilities are subtracted from assets”. It’s also important to note that at the time, Apple had a large stake in a company called ARM. ARM’s valuation increased markedly in the years that followed, and Apple sold down this stake, reportedly making $1.1bn in the period between 1997-1999.

But this campaign wasn’t solely for financial analysts. It also aimed to instill confidence in another very important stakeholder: customers.

“…with the publicized record of Apple’s financial troubles, many of them [customers] were not purchasing new Apple systems for fear that the company would soon fold, leaving them with obsolete machines. ‘‘Our number one priority was to make people realize that we were still here and still fighting for this brand,’’ said Rhona Hamilton, a marketing representative for Apple.”

— Abey Francis

Thinking beyond customers

We can’t ignore these “beyond-customer” effects, because they can influence everything from supplier agreements and employer branding efforts to pricing and more. These are intangible elements that are often difficult to measure—a concept Alastair Thomson agrees with.

“I’m not convinced that everything worthwhile can, or should be condensed into financial numbers…just because something can’t be measured doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea”

— Alistair Thomson

The problem is that brand advertising marketers often use these indirect benefits as a get-out-of-jail-free card when questioned about the commercial impact of the investment.

One common example is, when faced with flat earnings after launching a brand campaign, many of these marketers fall back on the argument that brand campaigns reduce pricing sensitivity, which in turn leads to superior profit.

This, however, is assumes that all brands can increase their pricing power and that advertising is the best and most effective way to do so. In reality, it’s far more complex than that. This is something Charlie Munger found out the hard way.

Charlie Munger (CM): They’ve [LVMH] just got a brand people trust so much. It took them a century to do it.

Host (H): Our conversation then turned to comparing Kirkland Signature as a brand to Hermes.

CM: Kirkland is a brand the way Tide is a brand. And Hermes is a different kind of a brand.

H: Yeah, Ferrari doesn’t make detergent.

CM: No.

H: We’ve spent a lot of time studying these brands. How do you look at the value of a brand?

CM: Well, it’s hard for us not to love brands since we were lucky enough to buy See’s Candy for $20 million – our first acquisition, and we found out fairly quickly. That we could raise the price every year by 10 percent and nobody cared. We didn’t make the volumes go up or anything like that. Just made the profits go up. So we’ve been raising the price by 10 percent a year for all 40 years or so. And it’s been a very satisfactory company. It didn’t require any new capital. That was what was so good about it. Very little new capital.

H: So what do you think? So there are categories, like See’s, or Hermes, where brands lead to pricing power? So brands lead to pricing power?

CM: I think your chances of buying one of them is so low. I wouldn’t even look, I don’t even believe in looking at things that I might find. You’re not going to get a chance to buy it.

H: But why do you think there are extremely well known brands in other categories? Maybe packaged food or something where…

CM: Well there are a lot of original investors that buy nothing but branded goods? And the one they usually start with is Nestle. And. I mean, they just filter everything. They’ve done two or three points better than average, but it’s not a bonanza.

H: After that, our conversation turned to Kraft Heinz and why Heinz is able to have pricing power while Kraft is not.

CM: It was very interesting. It’s something about the flavor of ketchup on a goddamn fried potato. People aren’t really willing to change brands over. They want Heinz. And so we could raise the price of Heinz. Pretty much any, but you try to raise the craft cheese and everything goes into rebellion, including the final customer, the housewife. They don’t care that much about whether the cheese is craft or not.

H: Why do you think that is, that some…

CM: Well, on the sauce flavor, it’s happened elsewhere. In Korea, one guy, he’s a Chinese guy, he owns all the sauces. Every single major sauce, he controls at least 95 percent of them.

H: Is it because sauces have such a particular flavor that no one can imitate the trade secret?

CM: Yeah.

H: And that gives pricing power.

CM: Well people get used to it and they like it.

H: Is that Coca-Cola, as well?

CM: Yeah, sure.

From trepidation to relegation

Yet, with all these potential benefits at play, it seems Steve took some convincing before green-lighting the campaign.

“This is great, this is really great…but I can’t do this. People already think I’m an egotist, and putting the Apple logo up there with all these geniuses will get me skewered by the press.” The room was totally silent. The “Think Different” campaign was the only campaign we had in our bag of tricks, and I thought for certain we were toast. Steve then paused and looked around the room and said out loud, yet almost as if to his own self, “What am I doing? Screw it. It’s the right thing. It’s great. Let’s talk tomorrow.”

— Walter Isaacson

It might also surprise you to learn “Think Different” is actually the last pure brand campaign Apple ever ran. Of course, this depends on how we define a “brand campaign” in the first place—something that’s often unclear and is discussed in Part 1. But even Apple’s famous “1984” campaign explicitly features a product (Macintosh), with clear references in the copy and a product shot at the end.

“Think Different” stands out as an extreme outlier in a number of ways. If you look back through Apple’s advertising catalog, you’ll notice every campaign post-1997 clearly featuring explicit references to products, features, or product usage contexts. Recently, they’ve even moved away from the inspirational copywriting style they were once famous for.

There is nothing particularly inspiring about this ad. No talk about values or beliefs, no emotional pulls on our heart strings, and no lofty promises about changing the world. Apple even announced their first black MacBook Pro in 2024.

Has the brand now come full circle? Have they turned into the big, monochrome computer company they originally positioned against in 1997 with the “Think Different” campaign? Unsurprisingly, famous copywriters began asking why.

Did Apple discover “Think Different” style ads didn’t work? Or did the company simply grow so large now that they no longer need to focus on that type of advertising? Why, 26 years later, did their advertising switch back to being highly product-focused, rather than inspirational and visionary? And finally, if “Think Different” was such a lauded success, why didn’t they repeat it? Why didn’t they iterate on this “successful” award-winning theme? Why didn’t they continue investing in pure brand advertising campaigns?

This is particularly curious because Apple has far more money to spend than before. They have more freedom to be creative, more leeway to soft-sell, or even waste the budget if they want. You might be surprised to learn that they don’t even have a tagline anymore. Perhaps, this famous campaign lives more inside the confines of the marketing industry than it does with the general public.

Shifting tides

It seems we may have finally turned a corner, where operators are beginning to realize the core issues with investments in lofty, purpose-driven brand marketing efforts. Unilever recently admitted they went too far, and Mark Pritchard from Procter & Gamble expressed similar concerns. But this is nothing new; it’s not like we’re short of examples where values-centric marketing doesn’t end particularly well.

While we don’t have access to the commercially sensitive data we need to say conclusively how effective this campaign was, we can still make a well-informed judgment call. Feel free to challenge me on this.

Based on the data so far:

Q: Did “Think Different” help galvanize a vision for employees and attract new talent?

A: Most likely.

Q: Did that contribute to future sales success beyond 2002?

A: Most likely.

Q: How much?

A: In mild, subtle ways that are very hard to measure. But the impact of the product itself would have far outweighed any lingering brand effects. .

Q: Did it help rectify trust issues and the fears customers and investors had with the company’s continued operation?

A: Yes.

Q: Did it help create a political buffer for Steve Jobs? Helping appease the board and allowing him more time to implement the turnaround strategy and helping deflect any undesirable short term results?

A: Yes.

Q: Did Steve enjoy the boost this campaign’s success gave his own personal brand and ego?

A: For sure!

Q: Did it help Chiat Day win lots of advertising awards and new clients as a result?

A: Yes.

Q: Did it have any significant effect on the company’s earnings at the time?

A: Not really. It wasn’t as impactful as many people believe it was.

In Part 6, a brand campaign buyer’s guide, we’ll delve into this in more detail in part 6 but, if you’re thinking of buying into a large advertising campaign, it’s always best to introduce some independent oversight (hint hint). If advisory services are out of reach and you’re considering buying a brand campaign, I would encourage you to read from Part 1 all the way through to this article, and then follow this rough guide below.

- Understand what a brand is and how they work—including what it means to each different stakeholder.

- Realize your advertising doesn’t need to be based on inspirational, beliefs, or values-based messaging in order to be effective. Brand science shows you should tie it to a product category in order for advertising to be effective.

- If you’re a less mature, smaller, challenger brand operating in a different context to Apple circa 1997, it’s probably unwise to emulate anything from the “Think Different” campaign.

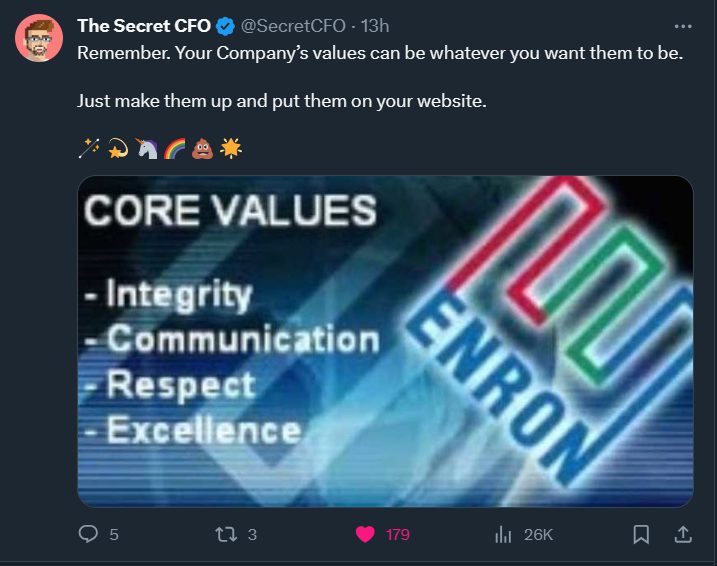

- Don’t cite “Think Different” as a good example when arguing for brand campaigns over any other type of marketing initiative. Including “performance marketing” (which wasn’t even around at the time). This campaign was an extreme outlier for Apple, and the by-product of a very specific point in history. There were also many other marketing initiatives—including direct-response style, product-specific campaigns, product placement, and product releases—supporting it at the time.

- Be very wary of anyone selling you a brand campaign under the premise it will lead to more sales revenue, profit, and market share.

- Understand the first principles of advertising and branding before falling into the trap of brand fluff or the “brand” vs “performance” false dichotomy. As Tim Doyle rightfully points out in his LinkedIn post, many are hoodwinked by this oversimplification.

Prove me wrong

I’ve argued that orthodox thinking about this famous “Think Different” campaign is wrong. But if you have a different argument, I would love to hear your perspective.

With all the things you’ve learned so far in this series here’s a quick practical test. Watch this video and tell me what you think about the arguments presented.

All of that aside, I still think these are the best 100 words of advertising copy ever written.

“Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.”

— Steve Jobs

Want to read more from John James? Don’t miss out on the other articles in this series:

— Brand Campaigns Part 1: What Exactly Are They?

— Brand Campaigns Part 2: Where Did They Come From?

— Brand Campaigns Part 3: How Does Brand Advertising Work?

— Brand Campaigns Part 4: Why and When Should You Use Them?

— Brand Campaigns Part 5.1: Thinking Different about Apple’s Think Different Campaign

— Brand Campaigns Part 5.2: Debunking Apple’s “Greatest Ad of All Time”

Cover image: Shahid Jamil