If you were to closely follow the sports world (as I do), you’d often hear podcast and radio hosts blurt out, “According to The Athletic…”. It’s an amazing achievement, considering the publication’s organic roots and the fact that ESPN is still the titan of that industry. Yet, The Athletic owns a disproportionate amount of sourcing, authority, and overall clout within its market.

The question is, how did it get here? And what can you learn from the brand’s ascent?

The Athletic, by the numbers

In November of 2024, The New York Times announced that its sports subsidiary, The Athletic, had hit just under 5 million total subscribers. This put the sub-brand up 1.72 million subscribers year over year and on a path toward profitability. Not surprising given it was just that summer that Reuters had reported a 30% jump in advertising revenue for the publication.

These are significant achievements considering that legacy brand Sports Illustrated has only three million subscribers. Meanwhile, the self-proclaimed global sports leader ESPN has 25 million subscribers to ESPN+ (its premium service), with reports stating that it lost 700,000 subscribers in 2024 alone.

To put this in perspective, ESPN+ doesn’t just offer its users access to premium sports analysis but to actual streaming sports. That has to be considered when comparing it to The Athletic, which does not. It also doesn’t surprise me to see ESPN subscriptions continue to sink. The brand has come under fire for its approach to sports reporting and is struggling—but we’ll touch on all of that later.

It’s interesting to compare ESPN to The Athletic. The latter is on the rise, while the former is seeing cracks in its seemingly impenetrable armor. I know, I’ve thrown out a lot of premises thus far that I have yet to substantiate in way, shape, or form. So, allow me to bring in a bit of data.

A deeper data dive into The Athletic vs. ESPN

While the bottom line matters, let’s leave subscribers and revenue aside for a minute to focus on The Athletic’s overall “digital performance”, instead. The outlet doesn’t thrive on social media the way some of its competitors do. (Social media is an area The Athletic should focus on more, to be honest.)

At the time of this writing, it only surpasses Yahoo! Sports in follower counts on both X and Instagram. Its engagement numbers relative to its followers are nothing special either, appearing rather ordinary upon cursory review.

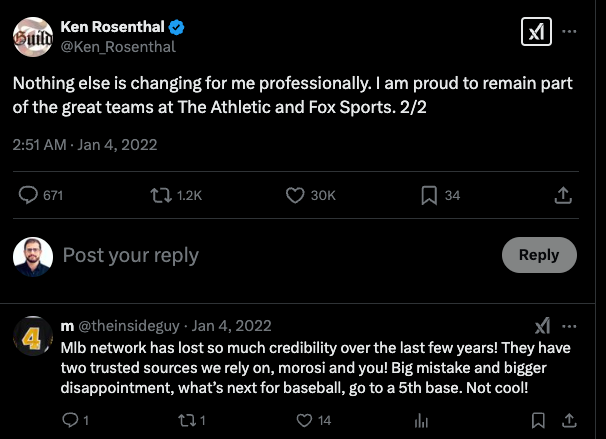

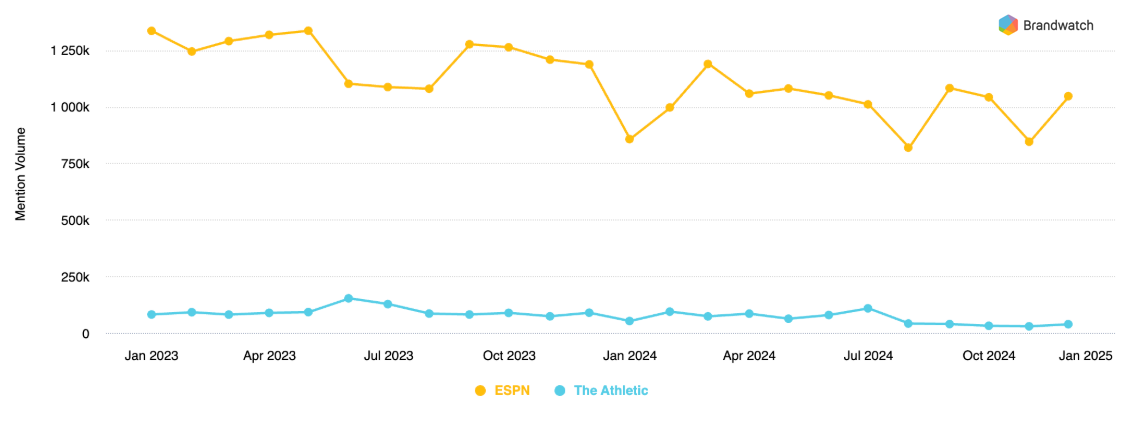

Yet, something interesting is happening on social media: Between January 2023 and 2025, for example, ESPN’s total mentions across social platforms went noticeably down (see chart below). As were The Athletic’s.

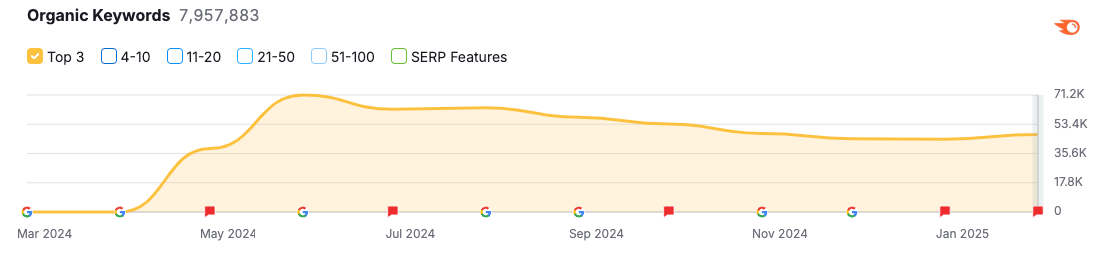

But the narrative is more complicated. In May of 2024, The New York Times killed theathletic.com and migrated the site to the main New York Times domain: www.nytimes.com/athletic You can see the site migration with traffic to the above folder (/athletic) only starting to accrue on May 28, 2024.

I speculate that people who once mentioned The Athletic by name have now begun mentioning The New York Times instead. It even took Google a month or so to pick up that The Athletic was now living under The New York Times domain. This correlates with when The Athletic started to see diminishing social mentions.

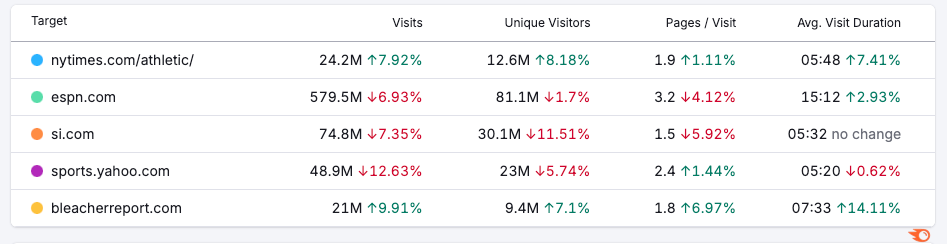

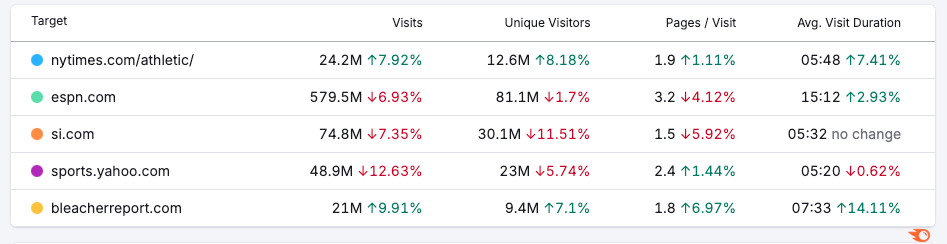

Speaking of website traffic, ESPN still dominates with 81 million unique website visitors per month and a total of 580 million visits over six months. Similarly, legacy outlets like Sports Illustrated and Yahoo! Sports outpace newcomers like Bleacher Report and The Athletic with a far larger number of unique visitors and total site visits from across all channels (e.g., Google, paid media, social, and referrals).

But that’s where it ends. All the other trends go in favor of the new kids on the block. Just look at the graph below: From the total number of site visits and unique website visitors to pageviews per session and how much time people spend on the site, The Athletic and Bleacher Report are the only domains seeing a growth trend across all metrics shown.

Again, what I see doesn’t surprise me. Sports Illustrated suffering a loss in unique website visitors of more than 10% is most likely due to their AI content scandal, for example.

A quick note about Sports Illustrated and AI content

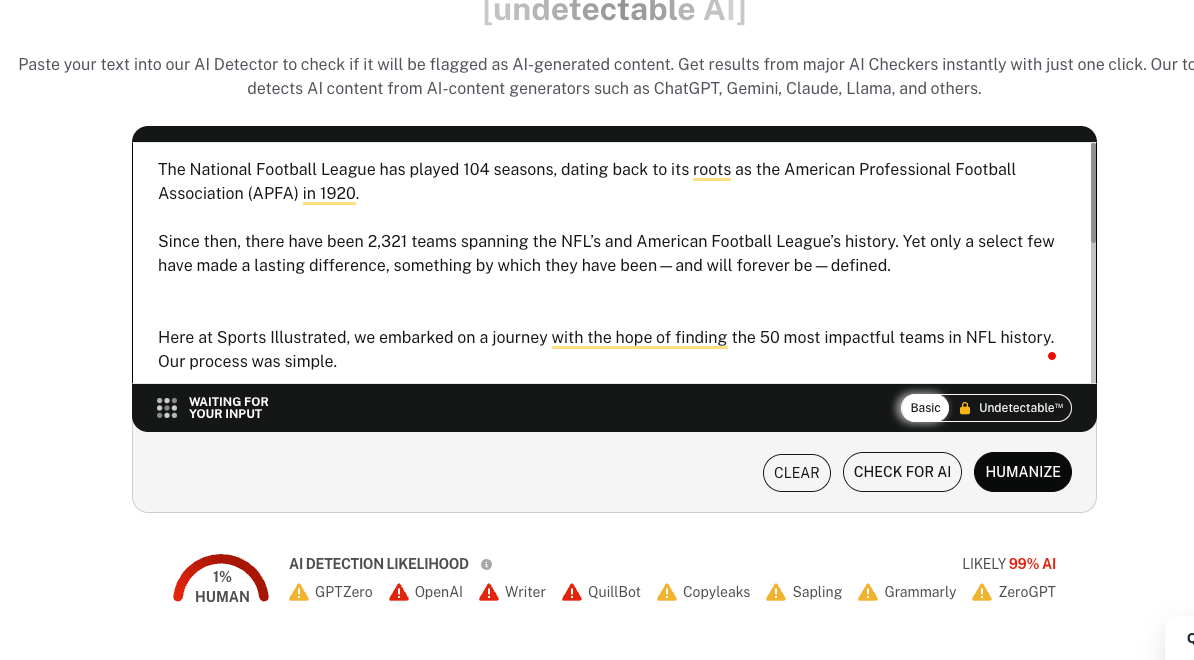

In 2023, Sports Illustrated was found to be using AI to create articles. After having been “caught” using AI-generated content, Sports Illustrated reported that it had removed the content from its site. And while that may be true, I’m here to tell you that it seems they’re still using it to generate new content.

According to AI detection tools, Sports Illustrated is still possibly using AI to generate content. It doesn’t matter if the tool is accurate or not; you can still see in their articles how the outlet tries to get around detection, relying heavily on large sections of quotes to counteract the AI content used. It’s all a bit nefarious. To me, this is a bit nefarious, considering how the outlet tried to get around detection.

The entire linked article seems to have been written for SEO purposes, which means that (once again) it’s no surprise that the site is seeing its brand and unique visitors both drop off extensively. The outlet hasn’t earned its trust back.

And the article in question is also not a one-off—it’s part of a bigger pattern. SI follows the same format for another article (also written for SEO, the way I see it) about Mike Tyson’s worth. If you remove the quotes, which again, I assume were only added to fool AI detectors, the results show the content has a 99% chance of being written by AI:

Here’s another example, this time about disgraced NFL quarterback Deshaun Watson’s girlfriend:

Below is another all about wrestler Hulk Hogan:

It took me only half an hour to find these examples. So, while Sports Illustrated may have taken down their AI-written content, it seems they have returned to using AI for a portion of their articles and are trying to be more covert about it. I cannot confirm this 100% given I don’t work at SI, but if it’s true, then you can see why the brand is all but dead in the water. Even if they aren’t using AI (again, it very much seems like they are), all of these articles smell like content written to rank on Google, not to be helpful or intriguing to humans.

The authority data driving The Athletic’s growth

While AI content has not plagued ESPN’s reputation, other things have (more on that later). Let’s bring back the chart from before:

Judging by these analytics, if it weren’t for average website visit duration, ESPN would be on a downward trend across all of its key performance indicators. And it’s likely the reason why this one metric is green is more because of live game streaming and less because of anything brand-related.

The “worldwide leader in sports” lost 7% of its total site visitors over the past 6 months. The Athletic? A 7% gain (and an 8% gain in unique visitors). With Bleacher Report showing similar numbers, something big is happening in the sports media space, and we’re about to get into the thick of it.

While ESPN is at an inflection point, I would argue Sports Illustrated and Yahoo Sports are already done (a story for another time). The real story here is that ESPN is on the verge of brand decline, while The Athletic and Bleacher Report are ascending to take its place (partially).

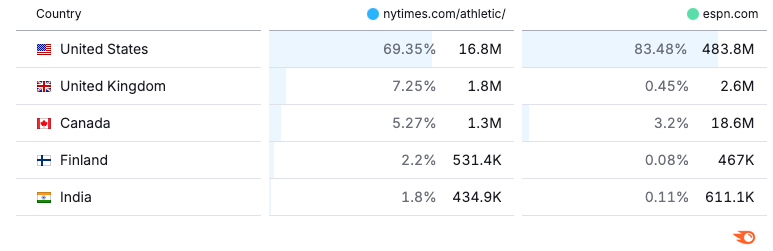

That’s all the more clear when you look beyond ESPN’s North American audience. In the UK, ESPN.com has only 800k more site visitors than The Athletic, and the gap narrows as you start looking around the world.

The online performance of The Athletic isn’t just part of some advanced performance marketing program (we’ll get to that, as well). It’s the result of its newfound market authority.

We’ll look at what the publication has done to earn its place in this niche later, but since we’re already talking about data, there’s one metric I’d like to share that directly points to The Athletic’s authority and may very well be the driving force behind its ascent.

Backlinks.

If you’re familiar with search engine optimization (SEO) data, then you know that the number of “backlinks a site has” become “signals” that Google uses to rank websites. That said, even SEO professionals often forget the origin story of the backlink.

What separated Google from the likes of AOL, AltaVista, Ask Jeeves, and the Yahoo’s of the world were links. Unlike other search engines, Google didn’t just look at the words on a webpage, it looked at links to the webpage, as well. This was called PageRank, and it’s the reason why Google is, well, Google.

The philosophy behind it was that links serve as a vote of confidence. If one site links to another, it must be because that site thinks highly of the content on the other site. A site that has accumulated many links is, therefore, more suitable for Google to showcase than one with fewer links pointing to it. While this is a bit of an oversimplification of things, the basic premise still holds true—when one site links out to another site, it means that they trust the site they linked to with their audience.

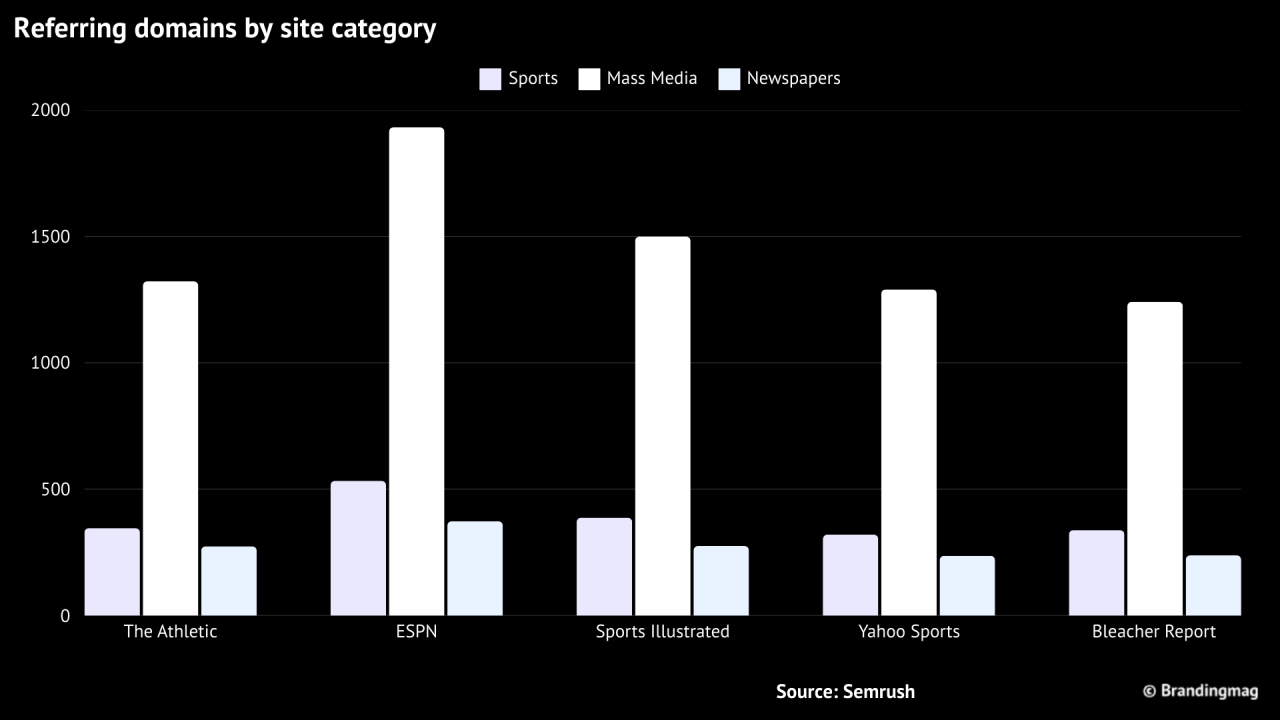

This is why I pulled the number of referring domains (that’s fancy talk for the “number of websites”) that link to The Athletic, ESPN, Sports Illustrated, Yahoo Sports, and The Bleacher Report. I didn’t look at the number of links, just the number of websites. This is because legacy sites, such as Yahoo Sports, will have accrued more links over time merely because they’ve been around longer.

But if we look at the number of websites linking to these sports outlets, we get more parity. One website can link to another an endless number of times. For example, Substack links to Brandingmag 279 times. What I wanted to know is not how many links these sports outlets have in total, but how many different websites found them worthy enough to link to.

I’m using the number of websites linking to these sports outlets as a proxy for how much affinity and authority they have across the web. I’m literally doing what Google used to do back in the day (and still does to an extent). And the numbers are interesting as hell.

First off, I only looked at websites that were relatively authoritative—meaning I filtered out all the spam sites that fill the web. Then, I parsed the number of sites linking to each outlet according to three categories:

- Sports websites (e.g., nccaasports.org, wnba.com, olympics.com)

- Mass media outlets (e.g., nbcsports.com, cbssport.com, foxsports.com)

- Newspapers (e.g., houstonchronicle.com, colordaosun.com, baltimoresun.com).

The pattern is consistent. The Athletic (and again, Bleacher Report) more than competes with the legacy brands. It has more mass media websites linking to it (i.e., is sourced more) than Yahoo Sports and Bleacher Report. Aside from ESPN, only Sports Illustrated has more sports websites and mass media websites linking (i.e., sourcing) The Athletic. Even ESPN has less than 100 more newspaper websites sourcing it via backlinks than The Athletic.

The reason why this data is interesting to me is that it means The Athletic is highly relevant. Sports sites and other media outlets are quoting The Athletic; in the real world, that’s what these links mean. They mean that other reputable websites are sourcing The Athletic just as much if not more than, than they’re sourcing Sports Illustrated and Yahoo Sports (and getting pretty darn close to ESPN outside of mass media websites).

That’s incredible. The Athletic has built quite a reputation for itself.

From my personal experience (as a sports fan)

It’s not fair. I’m coming at you with a lot of data and information, and it almost seems slanted towards The Athletic’s benefit. That’s because I’m starting from a far more anecdotal place. I consume an absurd amount of sports content each day. YouTube videos, podcasts, sports radio, you name it.

Too much, as my wife often reminds me.

One of, if not the only benefit, is that I can tell you firsthand that The Athletic’s content is disproportionately sourced within the sports media world (which is why I knew the backlinks data would show what it showed). It’s not ESPN, it’s not Sports Illustrated, and it’s not the Bleacher Report. It’s The Athletic.

I cannot tell you how many times a sports analysis show of whatever kind will say, “A report from The Athletic says…” The Athletic is breaking and breaking down sports news like few others. And you don’t have to take my word for it, you saw the data.

Still, it’s hard for me to show you what I mean since I assume you don’t consume hours of sports radio. (Ironically, I listen to ESPN Radio’s New York vehicle a lot). What I can attempt to show you, however, is just how often The Athletic is quoted on some of the industry’s most important outlets.

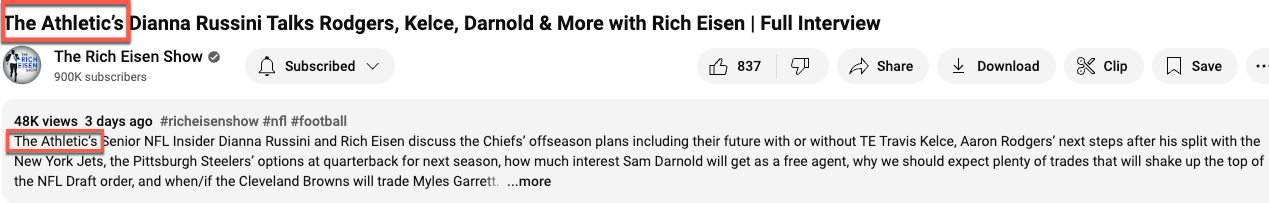

There’s no data (at least that I have access to) that can show you this. But, I do know—again, due to the copious amount of sports content I consume—that when a sports show interviews someone and throws up a YouTube video of it, they list where the guest is from.

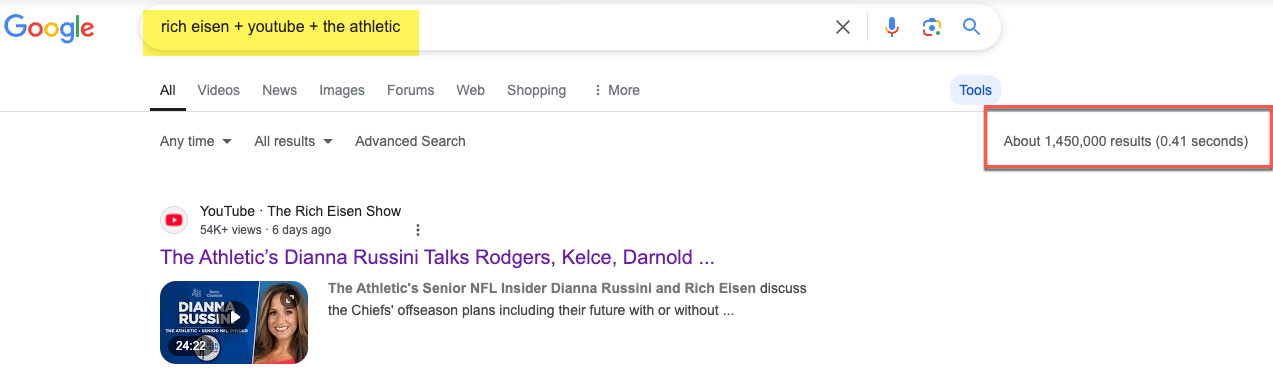

This means we can run a Google search (show name + youtube + outlet) to bring up only YouTube videos where the outlet is mentioned and see how many results we get.

This is not, by any means, scientific and is filled with a slew of methodological flaws. However, with as many off-the-mark results as you get here from Google, you also get videos where the media outlet is only mentioned verbally. This is because Google is able to take YouTube transcripts and recognize entities that were verbally mentioned. Given that connection, Google can show these YouTube videos as results for when someone searches for that named entity.

You can literally see this process right on YouTube.

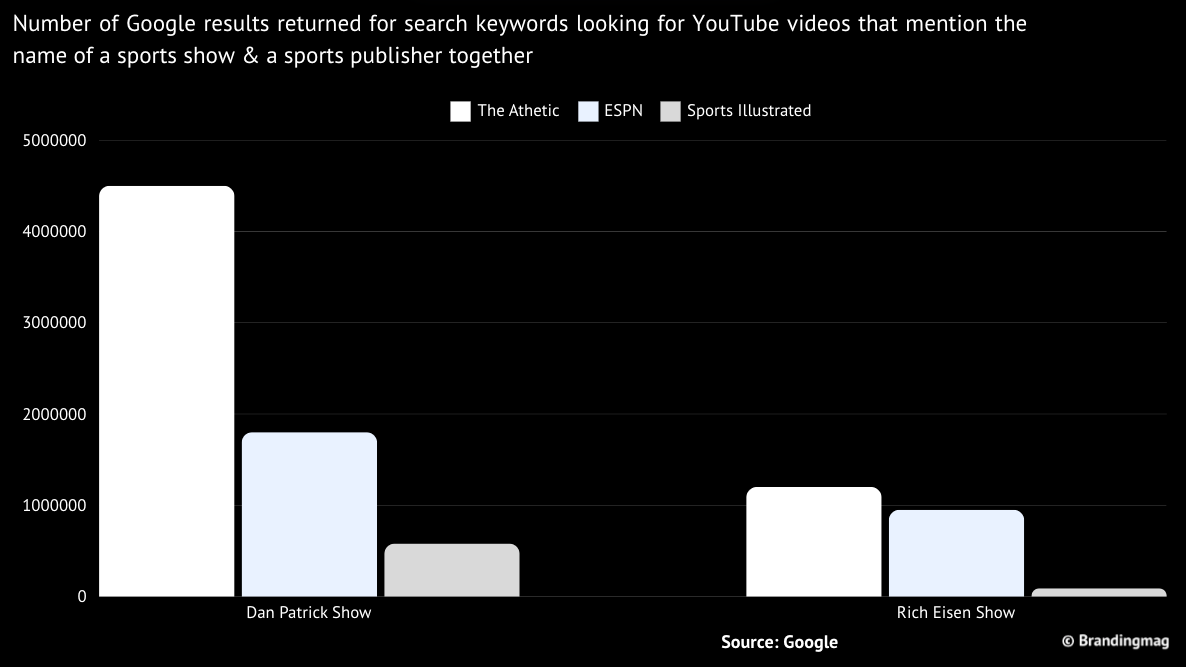

For whatever it’s worth (which is questionable), I ran this for ESPN and The Athletic using two popular syndicated sports programs that host content on YouTube: Dan Patrick and Rich Eisen. Why these two? Because they are extremely popular, deeper than most of these sorts of shows, and both used to work at ESPN.

Again, all I did was run a query like dan patrick show + youtube + espn and compared the total number of Google results to those resulting from a query like dan patrick show + youtube + the athletic.

Here’s what Google gave me back:

It’s not even close. Despite their ties to ESPN, both shows pull up far more results on Google for The Athletic. In the case of the Dan Patrick Show, we’re talking two million more results.

It makes sense to me. I hear The Athletic’s name come up far more often than even ESPN’s. To corroborate this, the number of results for Sports Illustrated brought up for the same kind of Google searches is just paltry. This aligns with some of the traffic data we saw earlier and is a big part of why I think this publication is basically done.

As an aside, this really shows you the power of brand on performance—a topic that isn’t discussed enough. Building a brand the right way results in its ability to perform better and for less money. The surge in subscribers, traffic, sourcing, backlinks, etc. that we’ve seen The Athletic garner is a direct result of its brand positioning.

But why exactly?

The Athletic is a story of two brands (not one)

To understand what makes The Athletic tick, it’s important to realize that it’s not one story about one brand. What makes the narrative of The Athletic so compelling is that it’s really the story of two brands.

The publication started as an independent sports news and analysis website in 2016. In a way, it was ahead of its time, offering a subscription-only business model.

That’s important to know because it speaks to what the publication has been about for years—authority and depth (which are the same thing). You can’t sell a subscription-based product where free alternatives exist unless you offer something above and beyond. That concept is built into the DNA of The Athletic.

But that’s also a very hard model with which to make a profit. For example, RollingStone tried this approach when the print magazine went out of fashion. The last I saw, it had 500,000 subscribers and couldn’t earn enough revenue. So, it ungated some of its content—about refrigerators. I’m not joking. RollingStone now reviews random products to bring in traffic from Google, and since the content (unlike the rest of its website) is ungated, it can try to earn additional revenue via advertising while killing its overall brand identity.

This problem eventually led to The Athletic being bought out by The New York Times in 2022. By mid-2024, The Times had ceased to write sports content under its banner; instead, all of the New York Times’s sports content was done via its sub-brand.

And it still works. Why? Because both brands have identical identities.

The New York Times, unlike RollingStone, was quite successful at pivoting to a digital-first world that relied on subscription. At the end of 2024, for example, The Times claimed it had over 11 million paid subscribers.

To understand The Athletic, we need to understand The New York Times. In a 2008 NPR interview, The Times’s Bill Keller was quoted saying, “Good journalism does not come cheap.” That’s a concept they banged away at for years. In 2023, I sat on a panel with Chanelle Kalfas, the Head of Brand Marketing and Strategy at The New York Times. Chanelle laid out the entire process they used to market getting people on board with paying for the news. Essentially, it was positioning not the brand but the news as something that can’t come cheap if you want it to be good.

The results speak for themselves. It’s a brilliant approach that’s both accurate and effective. It’s also the same approach The Athletic had taken for years, far earlier than even The New York Times to a certain extent.

The brilliance of partnership (and acquisition) in action

The brilliance of what The Times did here wasn’t that it acquired a well-respected publication; it was that it bought itself. It acquired an entity that seamlessly fit into its narrative. Too often, brands partner with or acquire someone that doesn’t align with who they are. There’s too much daylight between them for the partnership to work as they envisioned it to.

In acquiring The Athletic, The Times looked at the synergy not just the revenue possibility. It took a brand-first approach because it recognized the power that brand has in driving conversions and, ultimately, revenue.

When a brand looks at the revenue possibilities first, it pigeonholes the brand synergy. As a result, the partnership can’t be truly impactful. (I’m curious how the Nike collab with SKIMS will work out because of this factor.)

Identity alignment was and continues to be the bedrock that allows The Athletic to flourish. It’s the root cause of everything we’ve already discussed and will discuss here.

Allowing for sub-brand independence

Initially, The Times was running two separate sports departments. It had its own classic sports section and The Athletic.

That’s interesting in its own right. The Times didn’t try to absorb The Athletic. More than that, it allowed for total independence. I can’t tell you how rare that is. I’ve worked with publicly traded brands with various sub-assets, and there’s usually a turf war over the content.

Not so with The Athletic.

In an interview from November of 2024, Claudio Cabrera (VP of Newsroom Strategy & Audience at The Athletic) specifically discussed the dynamics between the parent brand and its sub-brand.

“I think what’s been really good about the relationship with The Athletic and The Times is that it’s been pretty independent, for the most part. So, there hasn’t been, ‘You need to do this or you need to do that.’ We are like two separate newsrooms…. When it comes to keyword targeting, those types of things too, there haven’t been any clashes or anything of the sort….” – Caludio Cabrera, VP of Newsroom Strategy & Audience at The Athletic

The point about keyword targeting is unique, and it speaks to why this whole thing has worked. Enterprise brands rely heavily on Google traffic to drive both eyeballs and revenue. So, when multiple content assets cover a similar topic, the performance (or SEO team) will fight to own those keywords in order to keep their key performance indicators up to snuff.

Seeing The New York Times sports section not try to dominate the “conversation” in order to keep its traffic metrics up is unusual and commendable. And it’s a big part of what allows The Athletic to maintain its brand positioning.

The Athletic is different from many of its competitors. ESPN hosts the NFL, NHL, NBA, and MLB (among other leagues), so how objective can it be? Will the NFL network ever say something negative about the NFL?

Sports media outlets having financial ties with sports leagues question their ability to remain objective. The Athletic, on the other hand, is independent. It doesn’t host live games or have financial contracts with the various leagues. People, therefore, trust that it’s not holding back.

This has been and remains The Athletic’s brand positioning.

“What we really try to communicate to the audiences when we introduce them to The Athletic is that this is a brand that’s independent of any sports leagues. Therefore, we can report anything and everything. So, we can hold the brands to account, we can hold TV networks to account, pretty much anything associated with sports. That allows us to gain the trust of the audience overall, versus there being this feeling like, whether it’s ESPN, NBC, or any of these other networks that have league ties, a viewer kind of saying, ‘Oh, are they not criticizing them because of this reason or that reason?’ And we try to really just keep that independence, in the same way that The Times does….” – Caludio Cabrera, VP of Newsroom Strategy & Audience at The Athletic

Allowing The Athletic to function independently was equivalent to allowing The Athletic to retain its core identity, brand promise, and market positioning. If The New York Times had done what so many brands do by imposing guardrails and performance restrictions around its sub-brand, I would not be writing this article right now.

It’s a pattern we see throughout the way the New York Times treats The Athletic, even now that it has become the sole provider of sports news within their ecosystem. (As we’ll soon discover when we talk about how the outlet treats its journalists.)

The performance impact of brand positioning

Before I explain how The Athletic leverages its journalists to build its brand, I want to go back to the first paragraph of this article.

“According to The Athletic…”

It’s not an accident. The Athletic is disproportionately referenced because of its brand positioning. Being an independent sports authority hyper-focused on quality and integrity pays off. It builds trust.

For the reasons I mentioned already, The Athletic set out to position itself as having an unparalleled level of depth, nuance, and reliability. The net result of positioning itself this way is that every sports podcast and talk show host now quotes one finding from The Athletic after another. These shows have built up the publication’s cache over the years. They fundamentally serve as a loudspeaker that says, “If you want great and unique sports coverage head over to The Athletic.”

The brand positioning is why the publication gets sourced so frequently. It’s literally how I first became aware of the news outlet. That’s the power of brand positioning done well.

The question is, how did The Athletic do this?

Advocacy is a brand power tool

Ken Rosenthal.

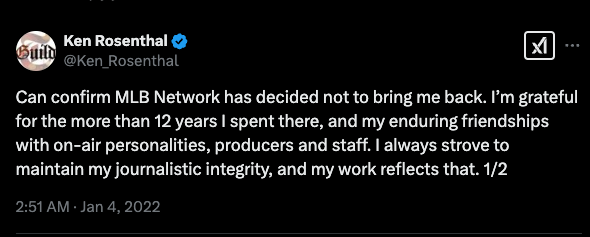

Known for his bow ties as much as his baseball, Ken is an on-field reporter for Fox’s coverage of Major League Baseball. Until 2022, he was a reporter for the league’s official cable TV network, the MLB Network.

He was fired for speaking truth to power. After 12 years at the network and after repeated criticism of the league’s commissioner, he and his 1.4 million followers were let go.

It’s everything we’ve discussed thus far. Where there are financial relationships between sports leagues and media outlets, there’s censorship. It’s a good thing The Athletic is around to stand out as a beacon of truth in the sports industry (assuming you care about sports).

Here’s the second part of his post:

I “forgot” to mention that Ken is one of The Athletic’s most recognized names, having written there since 2017. And the first comment under his post says it all. Ken has authority. Getting fired for calling out the commissioner of a sports league on the league’s own network gives him an extreme amount of “street cred”. And Ken uses that cache naturally (whether consciously or not) to build up the authority of The Athletic.

I’ve run advocacy programs for a good portion of my career, and I can tell you that brands do this all the time. They bring in a known figure from their vertical and build authority off their backs. It’s more than a brand ambassador, it’s a brand advocate.

Advocates, in my experience, are most effective when they’re not peddling their company’s product or service. They’re effective for a brand when simply “doing their thing” and interacting with their community as organically as possible.

This is essentially what’s happened over time at The Athletic. Is Ken Rosenthal going out there telling everyone, “Read The Athletic!”? Nope. He’s writing strong content and interacting with his community authentically by doing interviews, being quoted, etc. He’s not peddling his content to talk shows. He’s a natural member of that community that’s gaining exposure—and The Athletic is gaining that same exposure with him.

More recently, The Athletic has been lifting authority from its main competitor by bringing on big names in the industry from ESPN. Reporters like Dianna Russini and Andrew Marchand have left what’s commonly known in the sports world as “the mothership” for The Athletic.

What makes that so brilliant is that these people are friends with current ESPN TV and radio hosts (having worked with them for years). This results in The Athletic being mentioned on ESPN’s own broadcasts regularly.

As a result of its brand reputation for serious and unbiased sports reporting, The Athletic has become a “neutral entity” that is regularly hosted on its competitors’ outlets. That’s good branding right there.

The freedom lives on

I want to return to Rosenthal because there’s a stark contrast between how ESPN and The Athletic go about their employee relationships.

A few former baseball players got together and created a massive sports podcast network called Foul Territory. The main reporter and one of their hosts is none other than Ken Rosenthal, which is interesting because he’s sharing information about the very things he writes about for The Athletic. You might think The Times would frown on this or outright prohibit it.

But they don’t, and I get the sense they actually encourage it.

As a result, not only does Rosenthal grow his authority, which directly benefits The Athletic (and The New York Times), but his colleagues have a place to gain more visibility as well. Due to Rosenthal’s natural connection to The Athletic, his co-workers are frequent guests across the podcast network. Double win.

This is noteworthy in and of itself. Most brands would never allow high-profile employees this kind of latitude. It’s the kind of forward-thinking that sees the trees from the forest. Sure, there might be a topical overlap between the articles on the publication and what its journalists share for free on podcasts. But at the end of the day, it brings more brand awareness and a significant amount of relevance and authority—both of which help the brand now and in the future.

This stands in sharp contrast to ESPN and its relationship with its employees, which comes off as semi-contentious at best. In fact, it often seems their Disney drama is not only a category of motion pictures but a way of operating. Case in point: There was a time when ESPN imposed an embargo on their employees, forbidding them to appear on a competitor’s show. Ironically, the show in question was eventually leased out to ESPN (we’ll talk more about that show later).

Then, there’s Stephen A. Smith—the most popular sports talk show host in America who also happens to run ESPN’s most important daily show.

In 2022, Smith launched his own podcast, and the timing was not accidental. There’s no way Smith ignored EPSN’s short-lived ban on its employees’ right to appear on competitors’ shows. (Again, notice how different that is compared to The Athletic, who seems to encourage it.)

ESPN has clear issues with the freedom of association its employees have. That didn’t sit well with their biggest star, who rightfully feels he helped build the brand as it is now. (Again, the contrast is amazing. While The Athletic sees the value of transforming staff into advocates, ESPN shoots themselves in the foot by tightening the leash.)

“And for me to have my own studio, to be able to build and make the kind of investment in myself, it was a statement per se, just in my mind, that I’m moving on up and I have future aspirations that extend far beyond the corridors of ESPN…and I wanted to send that message and I wanted the world to know that.” – Stephen A. Smith

You don’t see The Athletic’s employees trying to send messages to management about their independence the way a 13-year-old might to their parents. At this point, it should come as no surprise that Smith’s ESPN colleagues don’t ever appear on his podcast. There’s no sharing of the brand authority wealth like you see with The Athletic. No, in this case, it’s all about Smith—and only Smith—and it’s palpable.

The irony is that by divorcing the show from ESPN entirely, not only is Smith not adding to the brand, but he’s also speaking volumes about it without ever saying a word. This is the flipside of brand advocacy: It’s often not what the advocate says that resonates, but what they don’t say (or do). Audiences attuned to the patterns and tendencies of a brand advocate can smell blood in the water—they can tell when something is wrong by the advocate’s silence.

Google is a good example of this. The megabrand has a group of so-called “Search Advocates” who help digital marketers better understand how Google works. After years of being incredibly active, this entire team took a step back, and the digital performance industry took notice immediately.

The same goes for their “Search Liaison,” Danny Sullivan. Danny was the founder of Search Engine Land (an industry news site) and was known for his criticism of Google. Google did the smart thing by bringing him and his street credibility among digital marketers in-house. Yet, over time, it became clear that Sullivan was being “nudged” to follow the party line and, therefore, avoiding to say certain things. The industry immediately recognized what Sullivan wasn’t saying and used it to draw conclusions (mostly negative) about Google. Search marketers’ perception of Google tanked as a result.

Like with Google, Stephen A. Smith isn’t the only one at ESPN “not saying things”. It’s a bit of a trend. Smith’s co-host, NFL Hall-of-Famer Shannon Sharp, has his own podcast. Not surprisingly, Sharp isn’t looking to help his ESPN “friends” out either. Seems that Sharp also knows the value of independence when working with large sports networks. The worst part for ESPN is that, while Smith has a nice audience, Sharp can get over a million views with one YouTube video alone.

That’s a lot of potential visibility and authority-building lost by ESPN. Because, even though Smith and Sharp defend the network publically, Shakespeare’s “Thou doth protest too much” rings through the airwaves (or, in this case, fiber cables).

If this doesn’t exemplify the benefits of brand advocacy, then I don’t know what does. For it’s clear that the leeway and freedom given to its employees (i.e., advocates) is the reason why The Athletic doesn’t have any of the negative stigma and drama that surrounds ESPN.

And ESPN only seems to be making matters worse. Now, in order to gain viewership, ESPN has gotten very “loud”. While The Athletic focuses on positioning itself as unbiased and nuanced, ESPN is literally doing the opposite by going all in on getting the most clicks rather than creating sourceable content.

Its shows are notoriously built on hot takes, heated arguments, and the like. ESPN poured gasoline on this fire when they paid Pat McAfee, a former NFL player with a widely popular and antic-filled YouTube channel, to run his show on ESPN. (Ironically, it was McAfee’s show that ESPN forbade its employees to appear on.)

In response to this, The Atlantic ran an article in May of 2024 entitled, “Pat McAfee and the Threat to Sports Journalism”.

Ouch.

There’s an entire Wikipedia page dedicated to the criticism of ESPN (no such page exists for The Athletic) on which it says, “Throughout its history, ESPN and its sister networks have been the targets of criticism for programming choices, biased coverage, conflict of interest, and controversies with individual broadcasters and analysts.”

More ouch.

In contrast, a February 2024 article by The Atlantic singled out The Athletic for its commitment to journalism by saying, “Many sports reporters continue to do vital work, of course, with The Washington Post and The Athletic (owned by The New York Times) leading the way. But their ranks are thinning, making it easier for athletes, owners, and leagues to conceal hard truths from the public.”

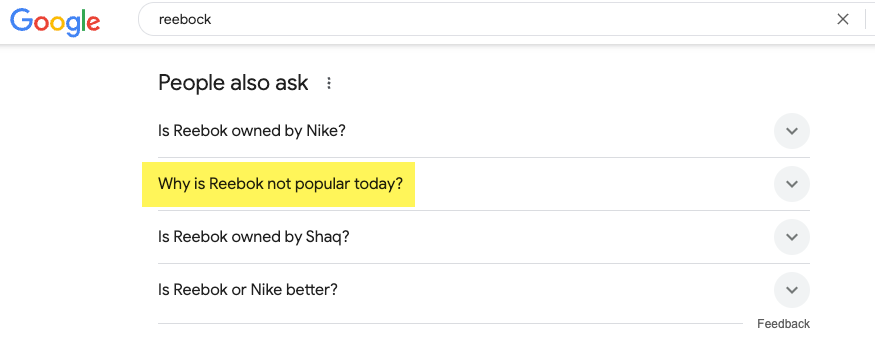

This sentiment compounds over time (as all brand sentiment does). You can even see it play itself out. One of the least utilized data sources for user sentiment is Google’s “People also ask” feature.

For many Google searches, the search engine displays a little box of commonly asked questions that users are asking. When you expand the tab to see an answer to the question, additional questions load. This way, it becomes a rabbit hole that helps you understand how people relate to a brand (among other things).

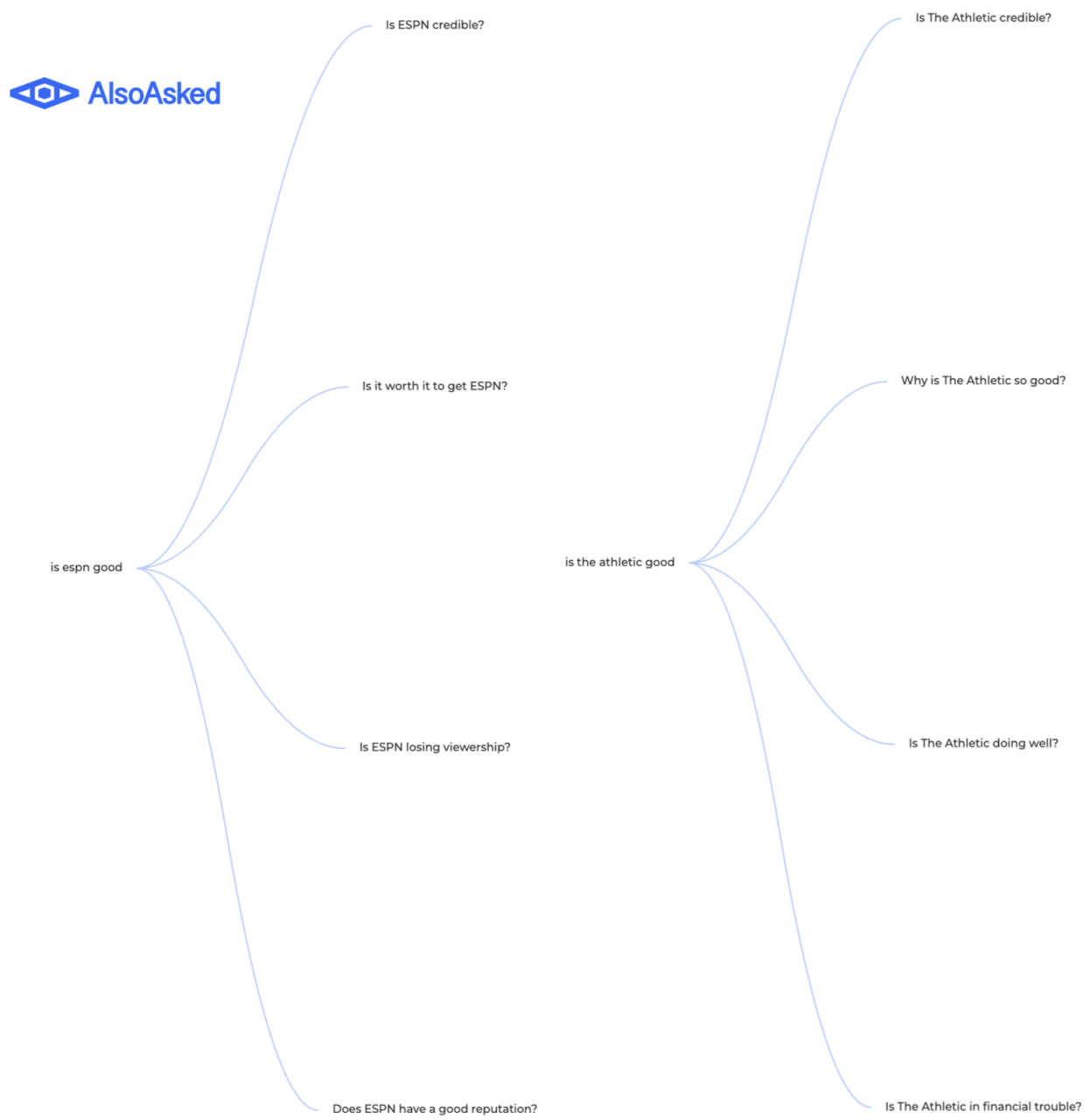

I ran the queries “is espn good” and “is the athletic good” through a tool called AlsoAsked that helps you mine this Google feature. There’s a very stark difference in the sentiment reflected in these questions.

Off the bat, the credibility of both brands is brought into question, and I want to make a point about this in general. There’s always consumer skepticism and hesitancy. It doesn’t matter how trusted or authoritative your brand is. People will always have a voice in the back of their heads asking if they should trust you with their hard-earned money.

Good brands get ahead of this. They understand that skepticism is healthy and normal, and they aim to address it. We’ve already discussed at length how The Athletic actively and specifically addresses skepticism around their credibility.

When I see the questions regarding ESPN’s and The Athletic’s credibility, it is just par for the course. Questions like “Is it worth it to get ESPN?” don’t signal anything negative about the brand. It’s pretty run-of-the-mill.

However, when you see the question “Does ESPN have a good reputation?”, you already know the answer is no. Why else would that question be one of the top four people search for in relation to the keyword “is ESPN good”?

In contrast, you have a question within the keyword “is the athletic good” that signals people assume the brand is great. If “Does ESPN have a good reputation?” implies negative brand sentiment, then the question “Why is The Athletic so good?” implies positive sentiment. You can see the net outcome of everything outlined thus far compounding and reflecting in these two seemingly innocent questions. In a way, they say it all.

The challenge ahead for any sub-brand

Leaving aside the volatility in sports media consumption and all that jazz, The Athletic not only has a challenge but an imperative going forward: To maintain its independence, authority, and brand freedom. From experience working for and with enterprise companies, this is easier said than done and is 100% not the norm.

It’s not easy to maintain such individuality in a big organization long term. While The New York Times has done an admirable job thus far, it’s all still very new. Can The Times keep big brand tendencies in check and allow The Athletic the breathing room it needs to thrive? I think it can.

It goes back to the perfect synergy between the parent brand and its sub-brand. They are one and the same. There’s absolute alignment at the identity level, which will continue to prove itself invaluable. The tension and subsequent struggle with competing goals that ruin things for so many brands in similar spots doesn’t exist here. I’m optimistic that The Athletic will have what it needs to thrive because what it needs is synonymous with what its parent needs.

That’s what a good acquisition looks like.