Why? Why on Earth would we want a virtual shared space that supersedes the Internet, populated by virtual entities? The hype surrounding the metaverse often overshadows its essence, the conceptual idea. The “meta-why” for a metaverse is that it promises humanity a new frontier of human experience, a fresh canvas for human creativity and innovation, and an expansion of human connection, all beyond the constraints of physical space, time, and cultural boundaries. It’s a transcendent world that has the potential to revolutionize the way we live, work, and interact with each other.

For brands, the idea of the metaverse might be relatively new, but it has already created a hunger to reach younger generations Z and Alpha with avant-garde, innovative experiences in the metaverse. What they’re quickly realizing, however, is that the exploration of this new frontier (while exciting) requires hard and truly innovative work–pushing beyond the limits of the known and taking risks that others shy away from. Timing is everything. Brands need the right technological, social, and economic conditions to make something this novel stick with their audience.

There are differing opinions on whether the metaverse should be a singular virtual world, a big shared virtual “meta” space where users can interact with each other, or a network of interconnected virtual spaces or “verses” for users to travel between. Regardless, the idea that we can travel in 3D between different worlds in seconds gives us a new perspective on reality.

But isn’t digital interaction a poor representation of real-life communication, you might ask? Futurist Aragorn Meulendijks, who goes by the name MrMetaverse, explains how the metaverse can humanize communication and interaction in digital life:

“Digital communication has been stripped of humanity and erased 6 million years of human communication, body language, facial expression, and use of voice. That’s why chatting leads to so many misunderstandings; it goes against how we are wired. That’s why emojis entered the digital scene, they give more nuance to the human expression without bodily expression.

Now, enter the metaverse where 2D becomes 3D on your screen. People get bodies (avatars) which makes it easier to communicate with each other in a more natural way. In 3D, you stand side by side which can bring back respect and appreciation. You can dance together and give each other a high five. Since many metaverses offer speech, people (avatars) also get a voice, so that we can hear nuances again.”

Meanwhile, Kees Elands (founder of Trendsactive), is critical about the metaverse’s potential to enhance human connections: “People of all generations worldwide are searching for meaning and social ties. But forming genuine relationships takes time and effort. We’re seeing a surge in loneliness among both the young and old, and we know connections alone are not enough. For instance, young people may have 1,500 social connections, but only a couple are truly meaningful. The metaverse has the potential to deepen these social connections, but it’s got to do more than just bring people together in a virtual world or let them play games. Genuine interactions are the key.”

The need for a safe place for counterculture

Stripping away the metaverse’s hype reveals not only the meta desire for a transcending world, but also the need for a world that is safe and trusted. A place to escape the content mills, speak freely, and cultivate counterculture.

Counterculture has a profound impact on art, music, popular culture, and therefore brands. In the 60s, counterculture opposed the “man,” a white heteronormative professional who represented oppression. Counterculturists believed that if they overthrew the “man,” anything (including utopia) was achievable. In the 70s and 80s, counterculture continued under this binary but, in online spaces, this strategy no longer works.

To understand today’s counterculture, we must view it through the lens of the Internet: it’s rhizomatic. “The man” is no longer just the establishment, but anyone living within the digital ecosystems of Google, Apple, Meta, TikTok, and Amazon. Today’s online counterculture is pushing against various norms and requires multiple sincere spaces and communities to explore these new ideas and beliefs.

Web2-born social media platforms proved to be the wrong place for it: counterculturists easily feel exposed when expressing themselves, surrounded by people who prioritize self-promotion over shared culture. People who please the crowd and avoid criticism rather than expressing themselves authentically. People who adopt current counterculture in the making and sell it with a one-liner. People who use shock for clicks, spearheading a superficial and watered-down expression of the culture before it even starts.

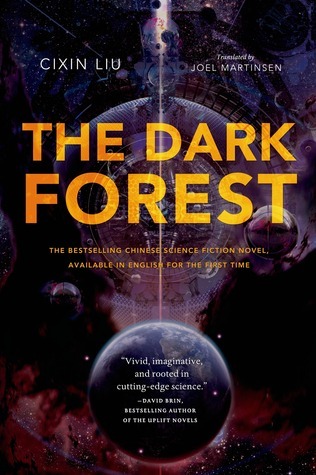

So, what does modern counterculture do? It seeks refuge in the dark corners of the Internet: in either the darknet or in so-called Dark Forests like Discord, Reddit, Signal, Telegram, and 4chan. There, users can engage without exposing their true identities to the platform. These places are less stressful and commercial, allowing counterculturists to speak and act freely without platform influence. And, since there’s a subcommunity for almost any specific interest or belief, this seems like a good solution.

These communities can, however, turn into echo chambers, reinforcing beliefs and shutting out or attacking opposing views. Insularity could very well be their downfall. If newcomers feel a barrier to entry and contribution, the counterculture space might eventually stagnate and fade out. As Aragorn told us, “In the real world, people can be held accountable for their actions. On the Internet, this is not the case and that leads to digital abuse. The forums or platforms can ban a user, but he can make a new profile the next hour from a different IP address. Internet culture becomes toxic because people don’t understand each other and fall into extremes. They communicate as if there are no consequences; you don’t get punched in the face for real. With Web3 solutions like Digital IDs, we can solve this.”

There’s an ongoing debate around DID’s and the (a)nonimity of avatars, but in a decentralized reputation system, an avatar’s interactions with others could determine their trustworthiness. This helps you decide who to trust and who to avoid in the verse–something you have difficulty gauging in mainstream spaces.

With this, the metaverse offers a new opportunity to both keep the Dark Forest subcommunity and offer more open connections. People in verses can freely experiment with rejecting mainstream values. They can create virtual lifestyles that prioritize imagination, collaboration, and community-building over materialism and consumerism. It’s a space where counterculture can be tested and built with surround visuals and sound, allowing people to immerse themselves in alternative lifestyles (some of which might eventually bleed over into real life).

The need for a qualitative and trusted Internet

The implications of all this goes well beyond the simple implementation of the metaverse.

Because even for those who aren’t looking to rebel, there’s a growing need for a new world free of the content farms that dominate the Internet today. The attention marketplace of the past decades was supposed to elevate good channels and drown out bad ones, but when the algorithm only rewards attention in the form of impressions and clicks, people and companies exploit it. The assumption that low-quality, dishonest, or dangerous content wouldn’t get enough interaction proved to be entirely wrong.

Content farms (or factories) have a simple and profitable business model: content for clicks. The more clicks on their channels, the more brands want to advertise with them, and the more revenue they generate. Their slick “life hack” pins, “test yourself” posts, and “wait for it!” videos are designed to look plausible and human-made only for you to find out that they don’t actually work. People try them, fail, and not only assume it’s their own fault but also react in the comments to ask why they failed, or why they can’t understand what went wrong. Since the content gets engagement (negative comments) and views, the algorithm rewards it by automatically pushing this content to the forefront. And the tech monopolies behind TikTok, Pinterest, YouTube, Instagram, and other channels have no incentive to change this because content factories generate ad money.

If low-quality content continuously dominates Internet suggestions, trust in content overall will decline.

But there’s more to it. Not only do algorithms prioritize factory content over cultured content (with the effect that people are less likely to see high-quality content), but the AIs of content factories are currently trained with human-made content. That’s their input at the moment. If the algorithm makes factory content outperform human-made content, however, humans will stop making cultured content for a living (or side hustle) since it’s no longer rewarding. It will become increasingly harder for the factories to find human-made content to train their AIs, leading to AIs trained on AI-generated content instead. It’s a downward spiral.

A very small man can cast a very large shadow

Another reason why the Internet will be roamed with factory content like never before is because of ChatGPT, Dall-e, and many AI video generators. Anyone can become a content factory now simply by giving these AIs prompts (including SEO and engagement guidelines) and sharing the resulting content on a regular basis. As Aragorn explains, “The magnification factor applies in the digital world. It’s like Lord Varys said in Game of Thrones: ‘A very small man can cast a very large shadow.’ In the digital world, one person can make a much bigger imprint than in the real world. He can multiply himself over different social media and forums. He can multiply photos, videos, text that might multiply again because people repost it, share it, engage with it. That magnification factor now becomes even bigger with AI. We can simply produce much more.”

Knowing that ChatGPT and all the other artificial content generators are trained with Internet content, it’s perpetuating the downward spiral of content quality: algorithmic in, algorithmic out.

As low-quality content also infiltrates Dark Forests like Reddit, people seek for a better Internet. One solution is a decentralized Web3 built with blockchain technology that destroys the monopolistic algorithms of tech giants. Since that solution is still in experimental mode, people turn to cultured content in Web2 creator pockets across Patreon and Substack. These types of platforms still, however, fail to address the need for a larger, trusted space–a space where culturists can live the content, touch it, experience it, and create it without algorithmic interference. A space, perhaps, like the metaverse that could (by the way) consist of many niche miniverses.

Knowing these very human needs, what can brands do?

Often, the first thing brands think of when ideating experiences for the metaverse is virtual events. Brands envision the crowds of avatars attracted to their experience, with everyone interacting, and they’re hooked. What those brands quickly discover is that ramping up an audience unfamiliar with being in verses doesn’t really lead to an engaging event. It takes time for people to know how to move, behave, and interact with others when in the presence of their avatars and those of others.

A better approach might stem from a shift in mindset: Knowing people want to test new, authentic ideas in a safe environment and that the metaverse might be just what they’re looking for, what can I (as a brand) do? This way, brands begin their meta journey thinking about how they can foster a sense of community among people who share similar interests in culture, help people connect with others who appreciate the same forms of cultural content, help people exchange ideas, and inspire people to collaborate on new projects.

One solution is offering a new way of creativity: born in the metaverse and only to be experienced in the metaverse. In other words, novel forms of cultural content that are not possible in the physical world. For example, brands can support visual artists and creators to create metaverse-only immersive artworks to be experienced via AR or VR, or invite musicians to use virtual instruments to create unique musical experiences that live in the metaverse but not on the likes of Spotify.

Kees has a rule of thumb: “Innovation should make people’s lives easier or more enjoyable. The success of social media and ChatGPT are examples of this. If the metaverse can simplify things for people, such as providing a platform for gaming, banking, and socializing with friends all in one place, it will become more interesting for people to be there. This is especially important in our complex society with too many choices and products, as it allows people to avoid constantly switching from one thing to another. Brands need to take note of this trend and adapt accordingly.”

Brands should also give serious thought to focusing on high-quality, cultured content made by humans. Sounds counterintuitive when discussing Web2.5, but more and more people are realizing that it’s not–it’s quite the opposite actually. And brands can capitalize on that in a way that’s conducive to the communities they operate (or would like to operate) in. One idea can be for brands to provide a space for the genuine creativity of those YouTubers and bloggers that once had a big following but were sidelined by the rise of content factories. The alt-TikTok community (TikTok’s counterculture known for quirky, offbeat content and a strong rejection of mainstream TikTok trends) is the perfect example of how a community can embrace individuality by featuring users with unique fashion styles, subversive humor, and non-conformist attitudes.

The need for trusted spaces within the metaverse

For brands that put social, cultural, environmental, and political issues ahead of profit, delving successfully into Web2.5 requires a focus beyond uniqueness. These are the brands that are well-positioned to create trusted unique spaces within the metaverse. This can be an intimate member-only miniverse, like a 3D version of a Dark Forest, where counterculture can thrive. These secure miniverses can be easily set up on platforms like Spatial.io to test the waters for a small group and (together) craft experiences that genuinely embrace countercultural principles and concerns.

Kees: “There seems to be a shift in online trust: the wisdom of the masses is a new foundation of trust. If the metaverse could become a hive mind, a place where people share wisdom, it can become a very interesting, trusted place for people to be in. Knowing that Edelman’s Trust Barometer shows that people trust brands more than, for instance, NGOs and governments, there’s an interesting role brands can play within that trusted metaverse.”

A metaverse’s safety depends on the creators’ and developers’ design decisions, so it’s totally doable. And if a brand can prevent the metaverse from becoming a cesspool of abuse and harm without resorting to surveillance (big no-no), it can earn trust and authority in the space. Not to mention that discussing safety with metaverse builders and shapers without resorting to surveillance would demonstrate leadership.

Brands need to let go of the data-driven ‘tracking your customer’ mindset. The metaverse is still an experimental place and the amount of user data collected by metaverses varies per platform. Generally, centralized metaverse platforms will collect personal information (such as name, email address, and perhaps age), device information (such as IP address and operating system), tracking pixels, and usage data (such as the frequency and duration of user sessions) but it doesn’t mean brands can access that data at all times. The same applies for data on user behavior within the virtual environment, such as interactions with other users, virtual items purchased or created, and the virtual locations visited.

Brands must realize that politics will inevitably creep into the metaverse as politicians and their influencers look for new ways to connect with younger voters and engage with audiences in an increasingly digital world. People (avatars) visiting brand experiences in the metaverse can have a political agenda and weave that into conversations with other visitors. Brands can attempt to maintain neutrality when this happens and avoid promoting specific political views or agendas, especially if they operate in countries with strict regulations on political speech and expression. Protecting user privacy and data of your visitors is especially important in the virtual world; in some countries, it’s considered a crime if someone with a political agenda talked to you, even if you didn’t talk back.

Which brings us back to the Dark Forests and counterculture. If a metaverse is centralized, identifiable, and commercial, the (counter)culturists will rather seek for the decentralized versions of the metaverse. Something to consider for brands when reviewing which metaverse fits their brand best, something I outline in the next article of my Web2.5 series.

Cover image source: anatoliy_gleb