In May 2019, Coca-Cola European Partners unleashed a premium range of signature mixers on the UK market. At launch, the range was heralded as an ‘exciting new frontier’ for the brand: building on its proud history in drinks and cocktail culture, updated to reflect a growing appetite for more complex flavours from an emergent generation of enthusiasts. The company collaborated with an international brand consultancy to develop an identity for the range, as well as investing significantly in a launch campaign that spanned social media, digital, outdoor, experiential events, bartender training, bespoke glassware, back-bar displays and menus.

Three years later (in October 2022), the range was discontinued. Why?

Certainly not through a lack of investment. The product had been co-created with mixologists. The opportunity had been validated through consumer research. The identity communicated the proposition clearly.

While the pandemic certainly didn’t help, a spokesperson for the brand explained to that the business was focusing instead on a streamlined portfolio of ‘hero’ products. Based on sales performance and feedback from consumers and customers, the decision was taken to focus on maintaining Schweppes’ leadership of the mixer category, rather than attempting to evolve Coca-Cola into a premium mixer brand.

This isn’t an exceptional case. It’s easy to find failed attempts at premiumisation. And if the world’s most valuable packaged goods brand can fall short, anybody can. Despite this, ‘premiumisation’ is a trend that never seems to go away. I work on brand portfolios across all sorts of categories (B2B, B2C and everything in between), and the question of when, where and how to premiumise crops up as frequently in B2B software and professional services as it does in tea and biscuits.

The sense is often that there’s a party going on and everybody wants to be a part of it. But there are good reasons to hold back.

I generally try to dissuade clients from making any assumptions about the attractiveness of the ‘premium’ segment of their market or sector. It’s easy to be seduced by the size-of-prize analysis, the high price points, the low price elasticity and the ability to talk about ‘craft’ or ‘provenance’ or ‘authenticity’. Instead, I try to focus on three questions:

- Is the party worth joining?

- What, if anything, can we bring to the party?

- Will joining the party enhance, complement, distract or detract from our current business?

Is the party worth joining?

It seems an obvious place to start, but you’d be amazed how frequently it is taken for granted that the ‘premium’ end of a market is a good place to be, particularly when ‘premiumisation’ is so often presented as a macro trend. I’m going to use anonymised data to illustrate my thinking here: they are real-world data points, with all the labels either stripped out or genericised. The below data is taken from a retail packaged goods sector in which brands have been categorised as either ‘budget’, ‘mainstream’, ‘premium’, ‘super premium’ or ‘artisanal’. I selected this example because the client was extremely keen to discuss premiumisation: the belief was that our (mainstream) brand was under threat from Private Label and that there was significant headroom for growth in more premium parts of the market.

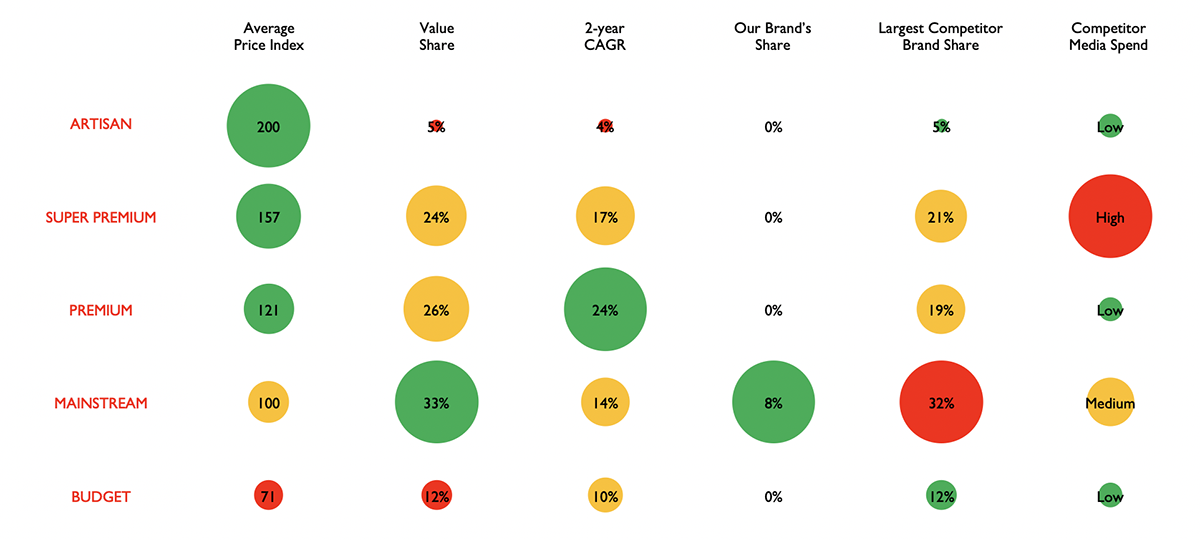

For each segment, the visual below indicates average price index (versus mainstream), value share of the total market, 2-year historical growth, segment share of the largest competitor brand and indicative competitor media spend. The ‘Our Brand’s Share’ column relates to our client’s brand: it has an 8% share of the ‘mainstream’ segment (far behind the segment leader, which has a 32% share).

So, based on the data below, is there an opportunity to premiumise?

Although our client’s brand doesn’t currently have a foothold in the ‘premium’ part of the market, this segment does look attractive: it accounts for just over a quarter of total value, it’s the fastest-growing part of the market, and brands in this space don’t seem to spend much on media, yet they command an average 21% price premium over mainstream equivalents. And based on the share of the biggest competitor in this space, the segment looks less intensely competitive than the mainstream space where we currently compete, which is dominated by a brand with 33% share.

The ‘super premium’ space is also potentially interesting: it’s also around a quarter of the total market value, it’s also growing impressively and brands in this space can command an average premium of around 60% over mainstream equivalents. However, the price premium comes at an obvious cost: a lot of money is being pumped into media by brands in this segment. This could be an expensive segment to enter.

The artisanal segment looks far less attractive: this is a tiny segment in value terms and isn’t growing significantly.

This is a small data set, but illustrates two general truths about premiumisation:

- Firstly, premiumisation isn’t a ‘thing’. Opportunities to premiumise are highly category-specific and there are typically different levels and types of premiumness to consider (and different ways to premiumise within each of these levels, so beware any catch-all advice on how to premiumise successfully).

- Secondly, the opportunity tends to tail off towards the upper echelons, as the distance from the ‘hump’ part of the market becomes greater.

So, we know based on the data above that there are two parties we’re potentially interested in joining.

Who’s at those parties? Will we be competing for space on a packed dancefloor? Or are there some empty spaces we could fill?

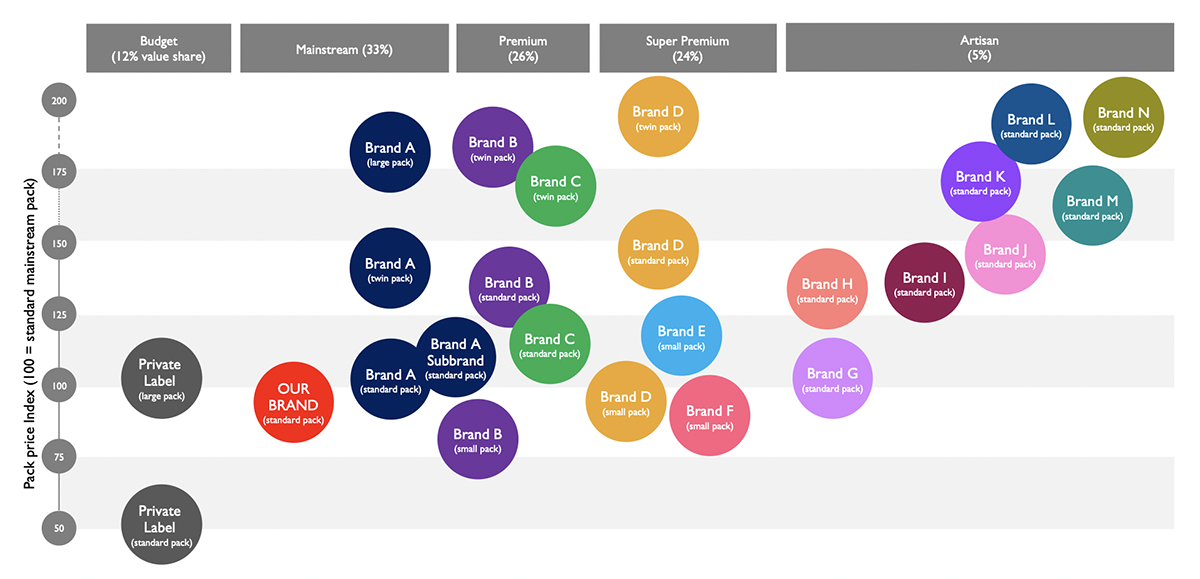

It’s helpful to map out the competition visually to see how crowded each space is, and if any gaps are revealed. The diagram below provides an indication of who the competition is and where they sit in terms of a price ladder (in practice, we’d look at a much broader data set across more dimensions but I’m trying to avoid this article becoming a thesis). At the bottom of the ladder are Private Label brands, which sell at a 50% discount to the mainstream average (indexed at 100 on the vertical scale). At the top of the ladder are artisanal brands in standard size packs, mainstream brands in large formats and premium/super premium brands in twin packs.

Our client’s brand (the red circle) competes in the mainstream segment with Brand A, which has a 33% share of the segment. It’s worth noting that the brand is priced to undercut Brand A’s standard pack: we’re the challenger brand in a segment dominated by a single large brand (which is available in a variety of pack sizes that stretch the brand across the price ladder). It’s also worth noting that while there’s space below us (only PL is cheaper in standard packs), there’s very little space above us: every rung on the price ladder contains at least one brand available in a standard pack. To extend our party analogy, these dancefloors are already busy and it’s difficult to see an obvious or large space we could fill.

Our client’s brand (the red circle) competes in the mainstream segment with Brand A, which has a 33% share of the segment. It’s worth noting that the brand is priced to undercut Brand A’s standard pack: we’re the challenger brand in a segment dominated by a single large brand (which is available in a variety of pack sizes that stretch the brand across the price ladder). It’s also worth noting that while there’s space below us (only PL is cheaper in standard packs), there’s very little space above us: every rung on the price ladder contains at least one brand available in a standard pack. To extend our party analogy, these dancefloors are already busy and it’s difficult to see an obvious or large space we could fill.

The artisanal party in particular is bursting at the seams: eight of the fourteen competitor brands are packed into this tiny space and many of these have clearly been squeezed down the price ladder: Brand G is selling at parity with mainstream Brand A in standard packs. In pure commercial and competitive terms, the artisan segment looks like one to avoid.

But the premium and super premium segments are also busy. We’ll have to contend with Brands B and C if we want to compete in the premium segment, as well as a ‘premium’ subbrand from Brand A (our mainstream rival). From a price perspective, this presents us with a challenge: our main rival has arrived at this party before us and is undercutting the incumbent brands. Our ‘challenger’ status has been challenged. And the super premium segment is being driven by Brand D, which has grown aggressively through a high and sustained marketing investment. There are few obvious gaps to fill: we’re late to both parties and they are in full swing. If we want to gate crash successfully, then we’d better make sure we can bring something interesting with us.

What, if anything, can we bring to the party?

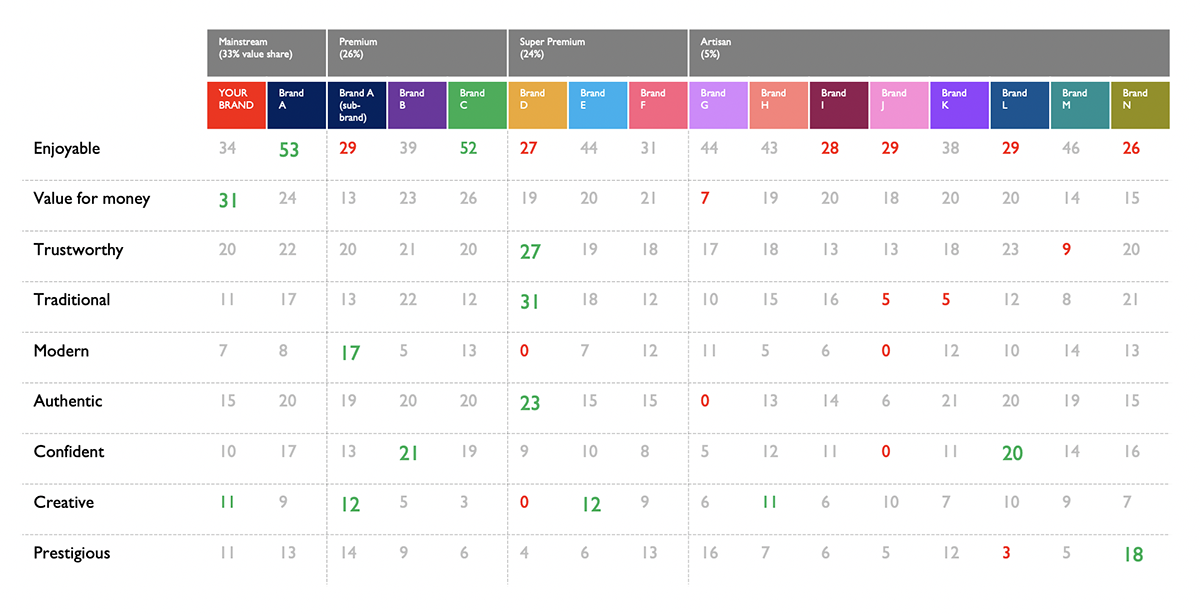

Below is some example data from our client’s brand equity study: top two box agreement with brand image statements (based on all consumers in the category who are aware of each brand).

One obvious point to note is that there are few genuinely strong brands in the category: Brands A and C have strong associations with enjoyment, but beyond this most image associations are weak. This isn’t good news for a category that’s worried about the threat of Private Label brands. Our brand trades heavily on value for money associations, so our client’s concern about this threat is well-grounded. But this is also likely to limit our ability to compete in premium and super premium segments of the market, where the leading brands rely more on emotive attributes, such as enjoyment, tradition, modernity and authenticity. Our brand is too weak to compete on those terms, so we’d either need to reposition our brand (away from value) to be able to stretch into more premium spaces, or we’d need to create an entirely new brand to compete in these spaces. There’s very little in the data to suggest that our brand has any chance of stretching successfully into premium segments.

This is a strategic issue that many brands face when they contemplate premiumising: there’s a great party going on, but they’ve got nothing (or at least nothing compelling) to bring to it.

In 2019, Coca-Cola saw that premium mixer brands like Fever Tree, San Pellegrino and Fentimans were attracting significant attention with stories of exceptional growth and decided it wanted to muscle in on the action with its enormously powerful mass market brand. By 2023 the GB market made it abundantly clear to Coca-Cola that they didn’t want to mix their super premium spirits with an enormously powerful mass market mixer. In the end, the people at Coke clearly decided that there are other opportunities out there that the brands in their portfolio are better suited to meet.

Will joining the party enhance, complement, distract or detract from our current business?

To recap: our client’s business is reliant on a brand that competes as a value-for-money challenger to the mainstream category leader. Although the premium and super premium spaces are commercially attractive and the brands in these spaces generally have a weak image, our brand is ill-equipped to compete. We could respond by creating and launching a new premium brand with a stronger positioning and identity than the competitive set, but we have finite resources and the Private Label threat to our existing brand remains a concern.

So, what do we do?

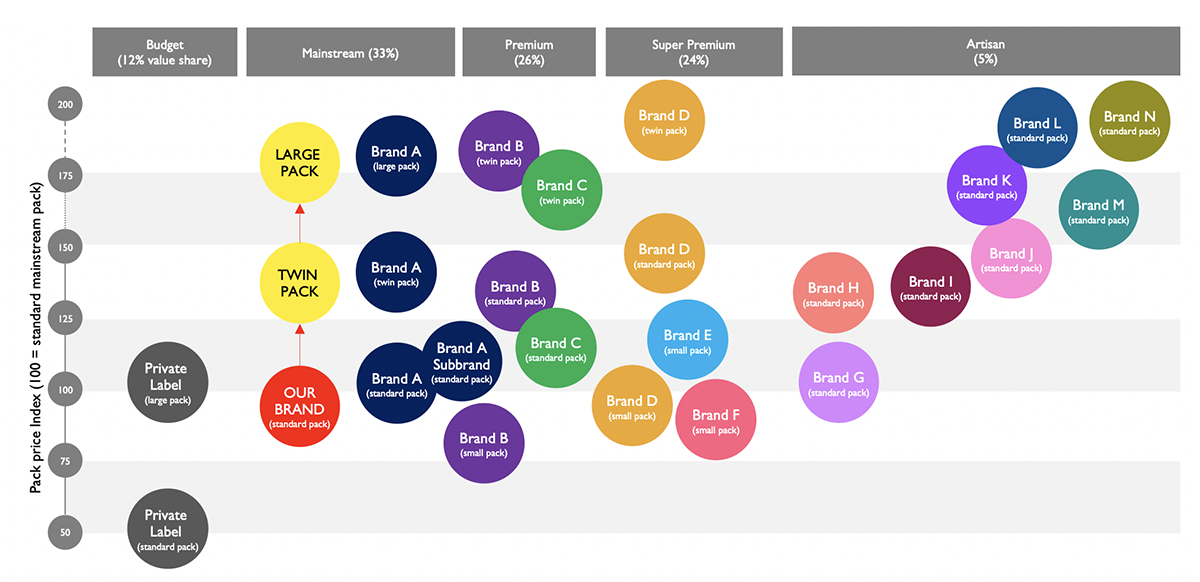

Brands A, B, C and D all sell twin packs and large format packs, in addition to their standard packs. In fact, a significant proportion of their sales are through these formats, which also give them greater visibility at fixture and more room to manoeuvre when contemplating pricing and promotional strategy. Our brand is currently only available as a standard pack, so a more obvious route to growth would be to expand the existing brand into new pack formats.

Brand equity data also suggest that we’ve got significant work to do to strengthen our brand, particularly if we are to fend off Private Label brands. So, the next most obvious thing to do would be to cultivate a clearer and more compelling brand image: priority number one is to strengthen the brand’s ability to compete against Private Label brands and Brand A in the mainstream segment, but there’s also an opportunity to explore whether repositioning the brand could help us to stretch into premium spaces in future. It was reasonable of our client to explore the premium opportunity, but closer examination suggests this should be regarded as a slow burn: there is a risk that committing to a strategy of premiumisation could have distracted our client from growth opportunities that are more significant and more attainable in the short-term.

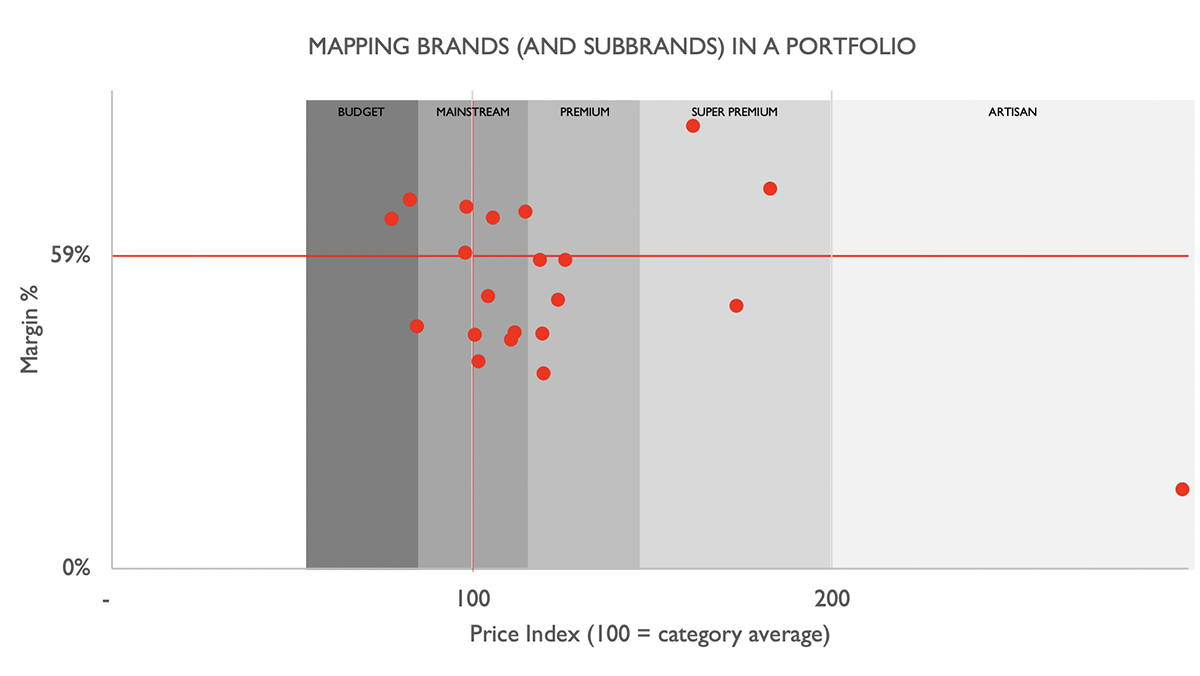

So far, I’ve focused on a client with a single brand and a single product, but what about portfolios involving multiple brands, subbrands and ranges that compete at different levels of premiumness? Here’s another anonymised data set from a client in another category:

Each dot represents a distinct product line and the chart above maps their level of premiumness (measured based on a price index, where 100 is the category average) against their average margin, expressed as a percentage of net sales. The average margin across the portfolio is 59%: any ranges that deliver below the horizontal line are margin dilutive, while ranges above the line are margin accretive.

Each dot represents a distinct product line and the chart above maps their level of premiumness (measured based on a price index, where 100 is the category average) against their average margin, expressed as a percentage of net sales. The average margin across the portfolio is 59%: any ranges that deliver below the horizontal line are margin dilutive, while ranges above the line are margin accretive.

The eagle-eyed amongst you will have noticed there’s some odd stuff going on here.

Most obviously, the range with the highest-price premium is also contributing the lowest margin (the solitary red dot at the far bottom right of the chart). More generally, there is no obvious relationship between the premiumness of a product line and the margin it delivers.

This is both a good thing and a bad thing.

On the positive side, this is because the business is actually pretty good at generating strong margins from product lines that carry a low price: you don’t need to have a premium product to generate strong margins. And that’s good news for this client, as 80% of their sales are in the top left quadrant of this chart: low-priced, high margin lines.

On the negative side, this also means that the business is poor at generating strong margins from higher priced product lines. And that’s a huge issue because all those dots in the bottom right quadrant are undoing the great work that the core product lines in the top left are delivering. Nearly half of the product lines in the portfolio are premium (or above), but every time the business successfully persuades a consumer to ‘trade up’ to one of these more expensive lines, it loses money (with two or three exceptions). This is the opposite of what should happen: if we’re going to ask people to trade up to more expensive lines, then we should make more money as a result. In cold, hard financial terms, premium ranges are detracting from the core business.

And this isn’t an exceptional or weird example: it’s very typical of the type of data I see. Premium brands and product lines are more expensive to deliver than budget and mainstream equivalents. This is something that’s easy to forget but vital to bear in mind if you’re contemplating premiumisation: being able to create a desirable premium brand or line is only half the problem: you have to be able to deliver it more profitably. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find out this was part of the reason for Coca-Cola’s discontinuation of its signature mixers. Coke has hundreds of years of practice at producing fizzy drinks efficiently at large volumes for the mass market. Inevitably, it is less experienced in how to produce artisanal mixers for a discerning niche audience and still make a healthy margin.

Succeeding in premium segments often involves learning to play by a different set of rules.

And that’s what explains the solitary red dot at the bottom right of the previous chart: it belongs to a small, artisanal pilot brand. The intention is not to try to find a formula for immediate success in the premium space, but to learn by managing a brand at the extreme end of the category. It sells through a channel that the business has no prior experience of (direct-to-consumer). It’s reaching an audience that the business has never traditionally interacted with. And it’s enabling the business to work with suppliers and partners that it wouldn’t normally deal with. Everything the business learns will eventually inform a better and more profitable approach to unlocking premium opportunities.

The charts and data that I’ve peppered throughout this article may have given you the impression that premiumisation is best approached with a cold and critical eye, but that’s only partly true.

Brands that live and breathe ‘premium’ are a different beast to mainstream and value brands.

Premiumness is embedded in their culture and decision-making. A large part of the difficulty in managing a portfolio that extends from mainstream to premium segments is that success involves deliberately cultivating cultural differences. Most organisations prefer to have a strong, single culture, rather than one where a ‘premium’ team invests lavishly while everyone else keeps one eye on costs and the other on consumers. Consultants like me experience this all the time: working with Prada and Wimbledon is different to working with Mars and Hyundai. It’s no simple thing for an organisation to be able to accommodate both ways of working.

That solitary red dot represents an organisation’s desire to learn to walk and chew gum at the same time. Premium lines are currently detracting from their business (and in many cases are distracting time and attention away from the lines that deserve greater investment). In the short-term, there will be an inevitable scaling back of premium lines and a focus on driving greater profitability across the portfolio. But the long-term opportunity is significant enough that the organisation is willing to channel some of those profits into experiments that help people gain first-hand experience of how to deliver ‘premium’ brilliantly.

The goal is to develop an approach to premium lines that complements the approach to budget and mainstream lines: the business will have learned to work at two different speeds.

Seen this way, it’s very possible that Coca-Cola’s signature mixers experiment will yield long-term dividends. Lessons may have been learned the painful way, but I’d expect that the teams involved have gained some valuable insights, relationships and ways of working that will carry forward into future successes. There’s no shame in an organisation dipping its toes into the premium space and often this is a more realistic approach than expecting to ‘win in premium’ by employing a playbook that has only been applied successfully to the mainstream.

The move from ‘mainstream’ to ‘premium’ is often larger than first appears. And not every organisation needs to make it. I’ve seen first-hand that the opportunity is easily overstated and the comparatively boring business of getting better at what you already do is often a quicker and surer way to create value. If you feel like there’s a party going on and you’re feeling a sense of FOMO, then ask yourself:

- Am I sure the party is worth joining?

- Am I clear on what I’m bringing to the party?

- And will joining the party enhance, complement, distract or detract from my current business?

Only once you’re happy that you can answer all three questions should you contemplate putting on your dancing shoes.

Cover image source: Fortis Design