Between 2001 and 2002 Brazil went through its largest energy crisis. The lack of infrastructure planning combined with economic growth forced the government to ration the energy supply from its main urban centres for intermittent periods of time. As a student living in São Paulo, I remember streets darkening as the sun went down. On one of those evenings, walking back home from university, two men driving a motorcycle stopped right in front of me. One of them jumped off the bike and before I knew it, he hit me on the head with the back of his gun and stole my backpack.

São Paulo is one of the many existing (and emerging) megacities feeling its growing pains due to an increased demand for ever more comfortable lifestyles. The logical response would be a cascade of actions from fixing the energy grid (obviously) to increasing police presence on streets and more. But is there a hack that could address the challenge faster and at a fraction of the cost?

Activating an unevenly distributed future

Fast forward to 2015, the year when Indian energy company Halonix relaunched its brand through the Safer City campaign, deploying LED billboards that lit up at night making streets safer. Following unprecedented explicit requests from the Indian population, the campaign then rolled out nationally.

Sustaining the trend, in 2018 Sberbank was approached by major Russian real estate developers to collaborate on better infrastructure planning in residential areas in Moscow. People’s opinions on local needs fuelled targeted campaigns, promoting loans for small businesses. The ‘Neighbourhoods’ campaign generated nine times as many small business responses as traditional loan advertising. In other words, people had their needs addressed with neighbourhoods becoming more attractive. The city also increased tax collection from the new businesses being set up, which reduced the cost related to dealing with derelict areas.

However, the above (and other similar campaigns that preceded and followed) were all stunts, great for consumers’ awareness and advertising award entries but short-sighted in terms of embracing a bigger commercial opportunity while addressing society’s most pressing issues.

Importantly, this is not about replacing the role of government in infrastructure but bringing brands closer to this through public-private-partnerships. “Cities will always need large infrastructure projects, but sometimes small-scale infrastructure can also have a big impact on an urban area”, as deliberated by the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on the Future of Cities.

It’s time to replace the morals of purpose with the utility of marketing

The issue with ‘brand purpose’ is twofold. Firstly, it’s a cost that requires sacrifices, reducing the effectiveness of marketing. While this can be avoided like in the case of ‘Newman’s Deal’, where Paul Newman gives away his face for free (because it drives sales) but only if the brands using this distinctive asset give their profits to children in need (taking purpose out of the brand equation and onto CSR). Secondly, many companies that have been investing in this type of narrative have had backlashes in relation to greenwashing.

Paraphrasing William Gibson’s famous “The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed”, Domino’s Paving for Pizza Program is the closest example of this type of partnership between brand, city, agencies, media owners and citizen-consumers. Aware that potholes, cracks, and bumps in the road can cause irreversible damage to people’s pizzas during the drive home, Domino’s decided to pave towns across the USA to save their customers’ pizzas from the bad roads. Obviously, not only Domino’s customers benefited from this effort, but every single driver going through the selected roads.

This may sound silly but according to the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission of the U.S. Congress, the annual investment required by all levels of government to simply maintain the nation’s highways, roads, and bridges is estimated to be US$185 billion per year for the next 50 years. Today, the nation annually invests about US$68 billion. Mayors and city managers from the municipalities where Paving for Pizza has taken place have acknowledged the creation of shared value. According to Bill Scherer, Mayor of Bartonville, TX, “This unique, innovative partnership allowed the Town of Bartonville to accomplish more pothole repairs.” For the city manager of Milford, DE, Eric Norenberg, “We appreciated the extra Paving for Pizza funds to stretch our street repair budget as we addressed more potholes than usual.”

From marketing budget to marketing investment fund

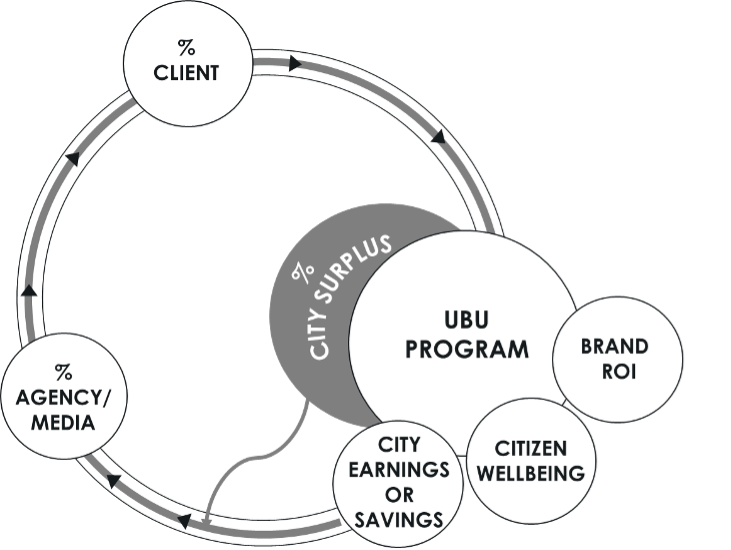

To ensure Domino’s action is not some sort of ‘freak’ activation, a mechanism allowing the mainstreaming of the approach is required. This mechanism would enable a surplus to be generated for cities by either reducing costs or creating new revenue streams that, in turn, improve citizens’ wellbeing. To work, rather than treating such activations as a one-off campaign, smart mayors would create a virtuous cycle, where a major share of the surplus is retained by the city, with the remaining redistributed to the advertiser, the agency, and media owner – a value unlocked only by repeating the approach.

Thus, the more advertisers communicate their messages in ways that benefit brand, people, and city, the cheaper it becomes to do more of it. And, the more cities encourage such an approach the faster societal problems would be addressed. Such logic can turn brand communications into a regenerative force for cities, where the promotion of goods and services is not only more profitable, but also environmentally enriching and socially virtuous.

This approach is already here. The approach just isn’t evenly distributed… yet. I coined it, Urban Brand-Utility (UBU). UBU is about using brand touch points as more than mere messengers to supplement public utility services of all categories. This way, marketing budgets are effectively turned into investment funds with returns in the form of brand cut-through, happier customers, social impact, and more effective city management.

Investing in creating demand for a network of creative urban resilience

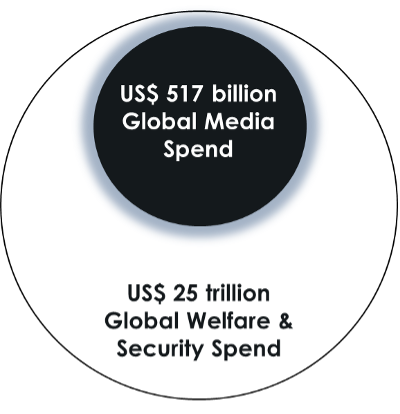

To offer some perspective, in 2020 global media spend in brand communications accounted for almost US$ 517 billion. Parallel to that, investment in Smart City infrastructure amounted to US$124 billion. When putting one next to the other, what we see is a 4:1 ratio, approximately. This means that for every dollar spent to improve our cities’ mobility, energy, safety, leisure, air, water, etc, four dollars are spent to sell us more stuff.

Through the UBU approach the US$ 517 billion global media spend (2020 figure) could be increased by another US$ 25 trillion, which represents the much larger pie of Global Welfare & Security spend, a figure obtained by dividing 2020’s Gross World Product (GWP) by the 30% global average spent on welfare and security as per the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The above provides a plausible scenario for advertisers to become key players in public-private-partnerships with land developers, architectural firms, mayors, and many other unusual partners able to completely reinvent their respective industries and transform society for the better.

If we are to address the many challenges cities now face, we must leapfrog and start building the future now. For brands and marketers, the shift lies in investing in your city rather than just marketing to it. With a billion people migrating to cities by 2030, this could represent a billion-dollar opportunity for repurposing our advertising infrastructure into a network of creative urban resilience. After all, as one of the tribunes asks the crowd in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, “What is the city but the people?”

Cover image source: Shays Brown